Once upon a time, in the old, old days when the mouse was a barber, and the donkey ran errands, and the tortoise baked bread, there was a great mountain called Kaf Daği on the border of the spirit realm, from which many of the fairytales and myths of the Middle East sprang forth.

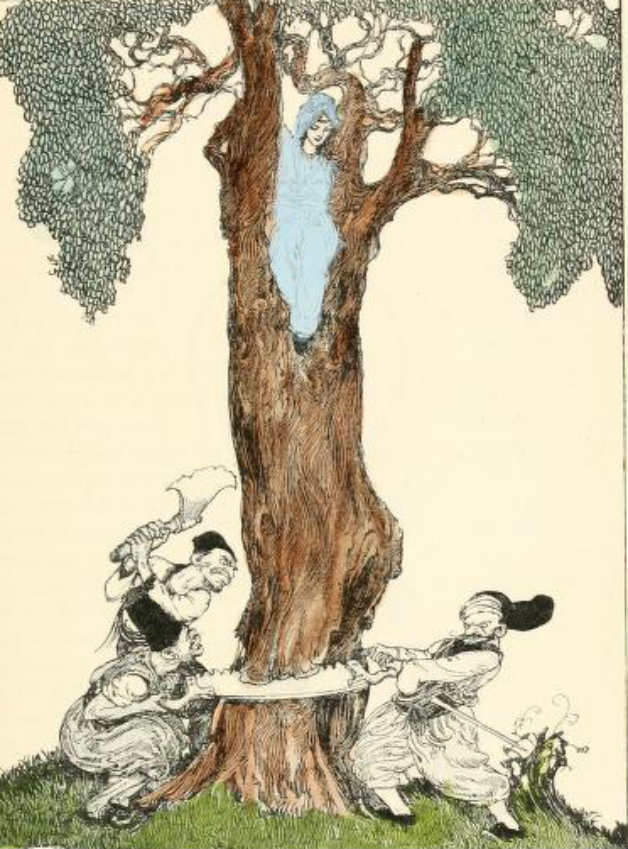

Today, Kaf Daği is thought to be somewhere in the Caucasus mountain range that separates the Black Sea from the Caspian. In this magical place – also known as Jabal Qaf in Arabic and Kuh-e Qaf in Persian – princes are cursed by witches, who turn them into stags; beautiful maidens are birthed from oranges; and sultans, courtiers, slaves and farmers alike are at the mercy of the peri (fairies) and ifrit (demons) that populate the Turkish fairyland.

The oral folktales of the Anatolian plateau are a remarkable blend of storytelling motifs and traditions, drawing on the Arabian Nights and Brothers Grimm, as well as Kurdish, Persian, Slavonic, Jewish and Romanian influences. Dr Ignatuis Kunos, a Hungarian Turkologist who was one of the first academics to collect and write some of them down in the 1880s, compared the treasures of Turkish folklore to “precious stones lying neglected in the byways of philology for want of gleaners to gather them in”.

He worried that the steady creep of modernisation – particularly the railway – would erode Anatolia’s cultural heritage. Happily, more than a century later, the oral storytelling tradition has survived, and a mammoth academic project called Masal is collecting and indexing a goal of 10,000 stories to preserve for future generations.

Members of the public and academics from university literature departments around the country can submit a fairytale to Masal’s online portal, where it is then examined by three rounds of researchers and language editors in a project funded by the Atatürk Cultural Centre in what is the first undertaking of its kind in Turkey.

The stories are indexed according to which of seven regions they are from and which of five different types of stories: animal tales, magical or extraordinary tales, realistic tales and humorous tales. Zincirlemeli tales follow a strict formula, almost like a poem, in which characters and events at the beginning and end form mirror images.

There are often several different variants of one story, requiring painstaking cross-referencing to figure out how a tale can differ over time from one region to another. For example, there are 20 different versions of Tın Tın Kabacık, about two little girls abandoned by their father, in the province of Muğla alone.

If a submitted tale is approved it becomes part of Masal’s online database, which will eventually be available to the public. More than 3,300 tales have been collected from 77 different areas to date, among them Kurdish, Laz, Armenian and Circassian stories and poems translated into Turkish. The project’s directors hope the corpus will be completed by February 2022.

Motifs such as magic carpets, animals and birds gifted with speech and enchanted mirrors, apples and pomegranates echo throughout the canon. Characters who brave the dragons and giants of Kaf Daği or survive a trek across the desert are rewarded with marriage proposals in beautiful gardens, and the phoenix-like Zumrutu Anka or Simurgh bird is always on hand to help a hero out of a tight spot.

The tales can be ugly, too. Black or Moorish servants, Jews and elderly witches almost always take the part of the villain; pashas have their innocent wives stoned to death and enemies ripped apart by wild horses; a sparrow comes to tell a young woman that death is her kismet (fate).

Turkish fairytales also took on an important political dimension during the early days of the republic, when modern Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kamal Atatürk, attempted to force what was left of the Ottoman empire into the modern world. Folk culture was rejected as backwards, and Turkish scholars such as Pertev Naili Boratav, who pioneered the study of folktales, became a target of Turkish nationalists in the 1940s for highlighting the country’s ethnic diversity in his work.

“Boratav’s meticulous scholarship and courageous public intellectualism inspired me,” said author Kaya Genç, whose book The Lion and the Nightingale criss-crosses modern Turkey in an examination of the “contradictory soul of the Turkish nation”.

“In folk tales, the heroes are mostly outsiders who suffer the violence of powerful autocrats; for politicians, their defiant tone is dangerous,” he said.

Dr Mehmet Naci Önal, a lecturer at Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University’s department of Turkish language and literature, who serves as one of Masal’s researchers, hopes that academics, writers and artists will be able to draw on the project’s database of stories for generations to come.

“Fairytales teach us to wonder, to use reason, to be patient, to dream, to overcome obstacles, not to be intimidated, to struggle, to be good people, to fight against evil, to tell the truth, to detect lies and deceit, to resist, and to listen. These values are universal human values: times change, people don’t.”

By: Bethan Mckernan

Source: The Guardian