More compelling evidence has been uncovered from trials that cast further doubt on the Turkish government’s narrative of a 2016 botched coup attempt, lending further credence to the claim that the failed putschist bid was in fact a false flag operation despite the relentless efforts of Turkish intelligence agency MIT, believed to be the key instigator of the plot, to contain the fallout from the exposure of fresh evidence.

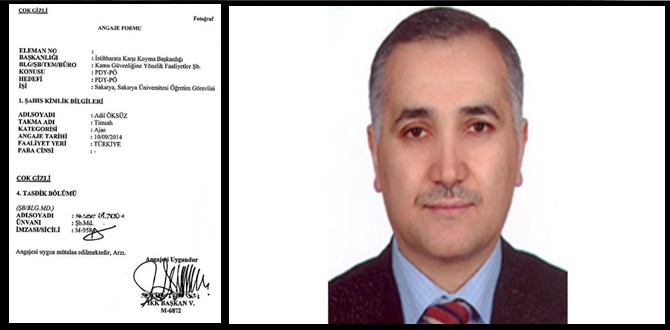

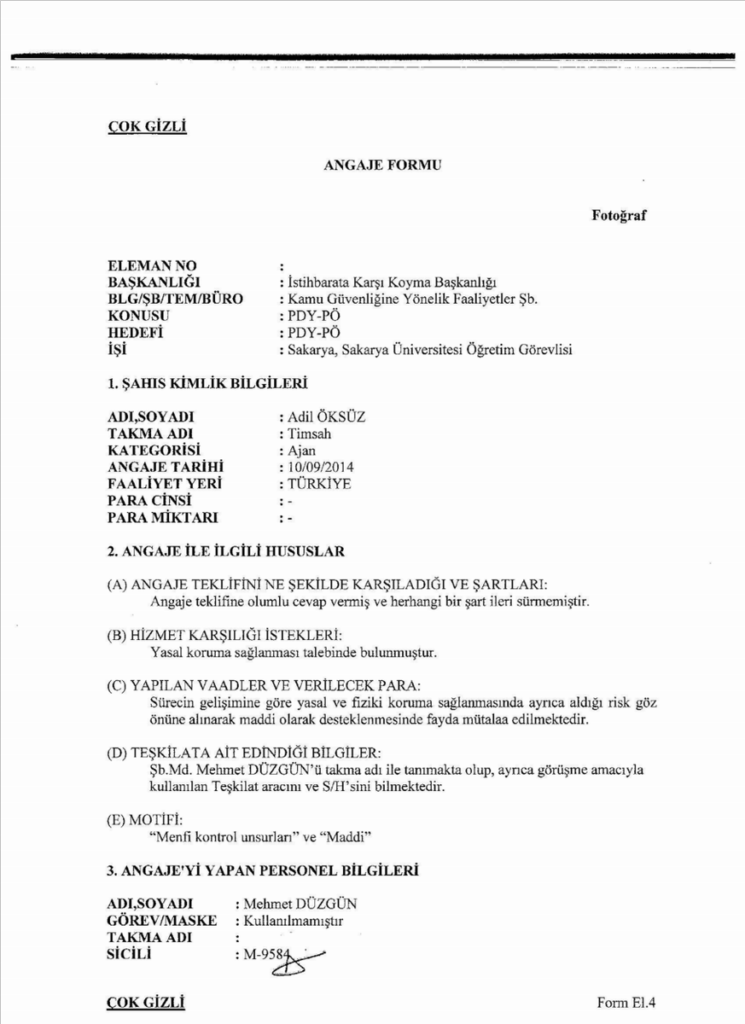

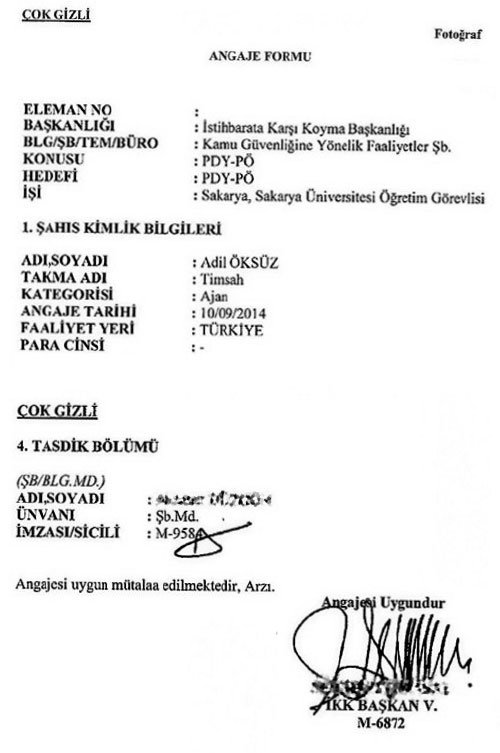

The most bothersome revelation for MIT appears to stem from the leak of a top-secret document that allegedly showed Adil Öksüz, a 54-year-old civilian who was accused by the government of playing a key role in organizing the coup bid, was an asset who worked with the spy agency to set up a group critical of the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan for mass persecution and help the Turkish president grab further power in his increasingly authoritarian governance of Turkey.

The document, branded as fake by MIT months after the exposé, seemed to be rather authentic according to senior military officers who testified in court during deliberations in the coup trials. A former MIT officer who worked in senior positions at the agency before retirement also concluded in his book that the document was authentic and that Öksüz was recruited by the intelligence agency two years before the coup attempt that took place on July 15, 2016.

What is more, MIT’s plot to pin the alleged forgery of the document on a fall guy — who was kidnapped while driving on a highway, thrown in a dark hole and tortured for months by intelligence agents — provided further proof for skeptics of the official narrative and strengthened arguments of those who claimed that the document was authentic and the coup was a ploy organized by the intelligence agency.

Öksüz’s quick release after a brief detention when all the other detainees in his group were speedily arrested at arraignment, a mysterious visit by a government advisor, an Erdogan’s confidant, to the detention site and Öksüz’s use of a GPS location device and cell phone while in custody all further reinforced the view that he had been a MIT agent all along and played his part to shore up the government storyline of the coup events.

Nordic Monitor has gone through tens of thousands of pages of court transcripts, evidentiary files in coup cases, documents, reports and discovery submitted to the judges to construct the profile of a man who was supposedly the number two suspect in the coup attempt.

The leaked document was first shared on Twitter by anonymous user @denizbayrak83 on November 19, 2016. But it had previously been communicated privately to some journalists and opposition lawmakers including main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who branded the coup attempt as mere theatrics. The opposition leader accused the president of carrying out his own coup on July 20 by declaring a state of emergency that gave Erdogan unprecedented powers, suspended the rule of law and led to the mass imprisonment of critics, opponents and dissidents who had nothing to do with the military or the coup.

According to the document that was titled an ‘engagement form’ (angaje formu in Turkish), a standard form that was part of a secret procedure for enlisting and recruiting assets, informants and agents, Öksüz was officially turned into an agent on September 10, 2014. He was given the code name Timsah (alligator) to keep his identity secret in line with the rules of the spy agency.

He was assigned to work for the Bureau for Public Safety Activities (Kamu Güvenliğine Yönelik Faaliyetler Şubesi), which is part of the counterintelligence department at the agency. He was given the status “agent,” which means MIT considered him to be an operative rather than merely an informant or an asset. He was highly valuable for the agency because of his wealth of knowledge of the Gülen movement and access to the leadership of the group, including Fethullah Gülen, who inspired the movement since it was first launched in the 1970s.

The document made a note that Öksüz asked for legal protection in exchange for his services, suggesting that he knew he was part of plans that amounted to illegal and unconstitutional activities and wanted to make sure he would be in the clear if things went sideways and the plots he was involved with were to boomerang on him.

The agency’s assessment note about him, included in the document, suggested that he be provided with physical protection and given money although Öksüz did not ask for any of it.

The document detailed the extent of Öksüz’s knowledge about MIT during his recruitment, and it was underlined that he only knew bureau director Mehmet Düzgün (MIT Personnel ID number M-9584) under a code name, a MIT vehicle that was used during secret meetings. The engagement form was approved by Sebahattin Asal (MIT Personnel ID number M-6872), the acting director of the counterintelligence department and signed by him. All the names and ID badges of the MIT officers who put their signatures to the document were authentic, corresponding to the positions they held at the time.

Interestingly enough, MIT did not say anything for almost five months after the document first surfaced publicly. When it was referred to indirectly by the main opposition leader, the agency eventually denied the claims in the document in a press statement posted on its website on April 6, 2017, a move that was quite unusual for an agency that shies away from issuing such statements. MIT maintained that Öksüz had never worked for the agency. But many in Turkey and abroad who followed the coup cases closely remained unconvinced given the notorious track record of the agency when it came to major blunders in its recent history.

Öksüz’s links to the intelligence agency were also raised by Fethullah Gülen, his one-time mentor who was accused of masterminding the coup attempt, in a July 2017 interview with France 24. Referring to the leaked document, Gülen admitted that Öksüz was one of the students in his study circle a long time ago and said Öksüz visited him in the US, like many others including senior Turkish government officials. But he denied the government claims that Öksüz came to get his approval for a coup attempt. Gülen, an outspoken critic of the Erdoğan regime on a range of issues from pervasive corruption to Turkey’s arming and funding of jihadists, has been a frequent target of vicious attacks by President Erdoğan, who apparently tried to pin the false flag on a man who had been living in the US since 1999.

SENIOR MILITARY OFFICERS SAY ÖKSUZ WAS MIT AGENT

The debate about the document was also heard in courtrooms overseeing coup trials during which many senior officers including generals and admirals who had no role in the coup or were vacationing at the time stood accused on dubious evidence that included fabricated phone records, computer logs that were tampered with, lies by secret government witnesses and statements taken under torture. Many defendants who brought up the document in their defense testimony argued that it was authentic, highlighting their viewpoint that MIT’s unusual statement of denial was in fact a confirmation of its authenticity.

Staff Col. Orhan Yıkılkan, who had served as chief advisor to then-Chief of General Staff Gen. Hulusi Akar, now defense minister, for years and was privy to highly confidential documents, told the panel of judges at the Ankara 23rd High Criminal Court on April 12, 2019 that he believed the document was authentic. He further noted that the document explained why Öksüz was released quickly after a brief detention near an air base right after the coup bid when practically everybody who was detained was sent to jail pending trial.

“I know this is true. I mean, this isn’t a fake at all. It is authentic. The signatures and the [names of] officials from that day are all correct. What would MIT say about it? Do you think MIT would say this is our guy? Has MIT ever admitted such a thing about any person, ever?” Yıkılkan asked the court.

“In my opinion, Adil Öksüz was used as an informant and operative in all these [coup] events, and he was successfully isolated [later] from the [criminal] case [by MIT],” he added.

Col. Muhsin Kutsi Barış, commander of the elite Presidential Guard Regiment who had worked closely with President Erdoğan, testified at the Ankara 17th High Criminal Court on March 13, 2019 and said there was no precedent for MIT publicly admitting to any of its agents or assets working in intelligence. “We’re talking about the National Intelligence Organization, it’s standard [operating procedure], nobody [in MIT] would say they’re my guys. There’s no such procedure in the agency,” Barış stated.

He also recalled that Eren Erdem, a former lawmaker from the main opposition CHP who claimed in comments on national TV that Fikri Işık, the then-minister of defense, secretly met with Öksüz in Sakarya province a day before the failed coup. Erdem was jailed in June 2018 by the Erdoğan government and released in October 2019 pending trial.

FORMER MIT OFFICER VERIFIES AUTHENTICITY

The use of Öksüz as an operative by the intelligence agency was also confirmed by Mehmet Eymür, a retired MIT official who served in senior positions in the agency’s special bureau and counterterrorism and operations departments for many years. Eymür claimed that Öksüz was recruited from the Gülen movement on the order of MIT, implying that the coup attempt was orchestrated by the intelligence agency.

According to Eymür, MIT turned Öksüz into an asset with the help of Kemalettin Özdemir, former Gülenist who has been working closely with President Erdoğan for the last decade or so to undermine Gülen’s leadership, divide his movement and secure the support of his followers for Erdoğan in elections. Özdemir and Öksüz were colleagues at Sakarya University, where they both worked as academics.

The leak of the secret MIT document about Öksüz shook the agency, Eymür pointed out in his book titled “Deşifre,” just like the leaked document about the killer in Paris. He was referring to the 2013 murder of three women affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) — Sakine Cansız, Fidan Doğan and Leyla Söylemez — who were apparently executed on orders from MIT.

The hit was believed to have been contracted to Ömer Güney, an insider who was recruited by MIT. A voice recording posted online in January 2014 featuring the voice of Güney suggested that the order for the murders came from MIT. In the voice recording, Güney talks at different times to two MIT officials and gives them detailed information about his plans and preparations for the murders.

Eymür also emphasized that the document about Öksüz that was shared on Twitter was not something that could be forged.

Questions around the leaked document were also raised during a debate in the parliamentary commission set up to investigate the coup. In a meeting held on November 23, 2016 opposition lawmaker Aykut Erdoğdu asked for verification from MIT by drafting an official letter from parliament addressed to the spy agency.

“Mr. Chairman, there’s a document called MIT Engagement Form that has been circulating on social media. I hope it is not real, but can we ask the MIT undersecretary about its authenticity?” Erdoğdu said. The chairman responded positively, but the coup report and its annexes including the response from MIT were mysteriously made to disappear from the parliament archives. The CHP repeatedly asked that the report in its entirety be located, but his calls generated no solid response from the parliament speaker or president’s office.

KIDNAPPED, TORTURED INTO ADMITTING FORGERY

Perhaps the most significant verification came from MIT itself when it plotted to abduct a man who would be forced to assume responsibility for the alleged forgery. The intelligence agency actually acted on that plot, thinking it would work to deflect attention away from the agency. The agents kidnapped a man in broad daylight when he was with his wife and children, kept him at a black site for months and tortured him to the point of forcing him to accept what MIT agents asked him to do. This actually made the containment efforts of MIT worse than they already were and appeared to have dealt a lethal blow to the intelligence agency’s efforts at denial.

Salim Zeybek, 40-year-old former employee of the Information Technologies and Communication Council (Bilgi Teknolojileri ve İletişim Kurumu, BTK), was abducted by MIT on February 21, 2019 in the Turkish border province of Edirne. He was taken to a secret location where he was subjected to torture. He suddenly appeared at a police station on July 28, 2019 after MIT agents turned him over for formal processing in the criminal justice system.

Zeybek’s wife was with him when three men in a vehicle forced him to a screeching halt and took him away. Despite dozens of witnesses, security cameras at the scene and multiple petitions filed by his wife with government agencies, the prosecutor’s office, the police and the United Nations monitoring mechanism on enforced disappearances, Turkish authorities conducted no investigation into his kidnapping.

Zeybek’s abduction was brought to parliament’s agenda on July 16, 2019 by lawmaker Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu, a prominent human rights defender. “Salim Zeybek, one of the abductees, was kidnapped in Edirne [province]. I asked the deputy interior minister, and he couldn’t say anything about it,” the lawmaker told the General Assembly. The kidnappers told Zeybek’s wife they were “the state” and that she shouldn’t meddle. The wife and children were taken to their home in Ankara and given some money, according to Gergerlioğlu. The lawmaker was recently stripped of his status in parliament over bogus criminal charges and arrested on April 3 by a police officer who had earlier been exposed as a torturer by the lawmaker on the floor of parliament.

When Zeybek suddenly turned up at a police station months later, he was forced to give a first official statement, based on a written statement he brought with him, claiming that he had been in hiding and decided to come forward to tell everything. He did not mention the abduction or torture and did not explain why his wife had been campaigning for months to find him. It was clear that he was terrified of going through that ordeal again if he did not go along with MIT’s instructions.

Zeybek made several claims including that he was the one who forged the leaked engagement form for Öksüz. In Ankara’s Sincan Prison Zeybek was kept in solitary confinement and not allowed to speak or socialize with anybody else. He did not even file a motion to challenge his long solitary confinement, which amounted to another form of torture under Turkish law and the European Convention on Human Rights, to which Turkey is a party.

For some time, prison authorities did not even send him to court during hearings in the case of the assassination of Russian Ambassador Andrei Karlov in defiance of the defense lawyers’ motions and the judge’s orders. It was clear that the intelligence agency was concerned that Zeybek might decide to spill everything and tell all in a change of heart. His abductors wanted to ensure he would stick to the scripted storyline by keeping him away from others in prison and preventing him from appearing at trial hearings.

During a court hearing at the Ankara 2nd High Criminal Court on January 17, 2020 defendant Hüseyin Kötüce, also in prison on dubious charges for his alleged involvement in the murder of the Russian envoy, vented his frustration over why Zeybek was not brought to court for cross-examination. Kötüce stood accused based on the testimony given by Zeybek and others. He said inmates in prison were not asked if they wanted to attend hearings, but rather were told to prepare and taken to the court with no questions asked.

MIT’s obstruction campaign became a nuisance for the court when several defendants who were accused based on Zeybek’s scripted statement filed repeated motions to compel him to appear for cross-examination. The judges eventually yielded to the pressure and issued several rulings to force him to appear as a witness on the stand.

When Zeybek finally came to a hearing on March 3, 2020, he seemed rattled, anxious and uneasy. His responses were evasive, vague and at times contradictory to his prior statement taken at the police station. His hands were shaking and he had difficulty maintaining eye contact. It was clear that he was traumatized by his ordeal at the hands of his kidnappers from MIT.

But the tricks to undermine the hearings did not end. At one point during the cross-examination, when he contradicted what he said in his police statement, a power outage hit the courtroom, shutting down the National Judiciary Informatics System (UYAP), which recorded hearings for court transcripts. That forced the court to take a recess. The power came back, and Zeybek returned to the scripted storyline by referring to his original statement.

Asked which computer he used to forge the engagement form, Zeybek said the computer had gone missing and therefore he could not prove how he forged the document. Although he said he did not have expertise in computer technology and received assistance from experts, he declined to give the names of the people from whom he got technical help.

When asked whether the police searched the safe house where he claimed he had hidden for months, Zeybek said the police did not search the place, which was quite odd given the fact it is standard police procedure to search the safe house for evidence collection when a suspect was found. He had difficulty remembering the names of his three roommates he claimed to have holed up with for three months.

In his police statement he gave the names of some 200 people whom he believed to be affiliated with the Gülen movement. When defense lawyer Ayten Izmirli asked him to recite all 200 names for the record in the courtroom, Zeybek declined and said could not remember all of them. Zeybek later reduced the number and said he knew only 30 or 40 or 50 at most. The defense asked him this time to recite the names of 30 of them, but the judge intervened and stopped the proceedings, saying there was no need to list 30 names in the courtroom. The defense said the judge under Turkish law cannot intervene unless a challenge is made by either the prosecutor or the defense, which was not the case. But the judge insisted and did not allow Zeybek to respond to the lawyer’s question.

Adem Kaplan, another defense attorney who actually helped Zeybek’s wife in her legal appeals to locate her missing husband, asked why Zeybek’s wife had spent so much time and effort to find him and gave interviews to Turkish and international media outlets. Zeybek said he had no idea why his wife did that. His wife, who had filed appeals with the Ankara Bar Association, the Human Rights Association and others, asking for an investigation into her husband’s whereabouts, mysteriously decided to withdraw all her applications.

Defense lawyer Izmirli said his team verified the authenticity of the signatures in the MIT engagement form and noted that Zeybek was kidnapped, tortured to force him to assume responsibility for the alleged forgery and was still being threatened with harm to his family unless he testified in line with the orders given by his kidnappers.

The court transcript of the hearing in which Zeybek appeared as a witness was also tampered with, and some of the statements were removed from the text, according to defense lawyer Kaplan, who petitioned the court to provide a copy of the tape for a review of the transcript. The defense especially focused on the judge’s unlawful interference in the hearing, which was later deleted from the transcript.

ÖKSUZ HAD GPS LOCATER, 2 PHONES, LARGE AMOUNT OF CASH WHEN DETAINED

Öksüz’s quick release from detention when all 97 other people in his group who were processed at the Sincan courthouse were formally arrested at arraignment also raised questions of why he was being protected and by whom. When judge Çetin Sönmez of the Criminal Court of Peace let him go on July 18, a prosecutor objected to his release, but that objection was rejected by judge Köksal Çelik as well.

Both judges were working for President Erdoğan’s special project courts, the Penal Courts of Peace, which were set up by the government in 2014 specifically to target critics, opponents and dissidents. The judges in these courts were hand picked by Erdoğan’s men. Considering the seriousness of the accusations and the fact that Öksüz was released twice by judges goes against common sense and defies logic when thousands were arrested indiscriminately.

Öksüz is believed to have served his function as an agent of MIT to falsely link the coup attempt to the Gülen movement, a group he was once a part of, with access to Gülen as one of his students. Perhaps he was detained mistakenly near the air base along with other officers in the chaotic environment on July 16, or maybe it was a deliberate move to cause him to leave traces so that the government could pin the false flag on the Gülen group. Whatever the case, the fact remains that he was quickly separated from the others and rescued from proceedings in line with the legal protection promised to him in the engagement form.

When Öksüz was detained, the gendarmerie seized two phones (a Samsung Note 5 and an iPhone 6), a leather briefcase, 11,450 Turkish lira and $3,600 in his possession. He also had a ZTE 4G LTE GPS locater he managed to hide and did not declare to gendarmes. The gendarmes discovered the device when Öksüz tried to discard it by throwing it into a toilet during a bathroom break shortly after he was brought to the gendarmerie station on July 16. A record of the incident was put in a document at the station and signed by three sergeants and the district gendarmerie commander as well as Öksüz, who admitted he owned the device. Another document signed on the same day showed that the GPS device was handed over to police chief Hakan Kutlu from the organized crime unit at 14:30 hours.

The district gendarmerie command was instructed by the government to turn over all the detainees and their belongings to the police, which was authorized to conduct probes, interrogations and the processing of suspects. Soon after Öksüz’s detention, six police cars and three unmarked cars arrived at the station to interrogate, process and take the suspects away. A group of detainees were shipped to another location by the police, but Öksüz was not picked up although the police said they would come back for him.

The district command was later told on the phone by the police to put Öksüz in a group of officers who had surrendered at the air base and were sent directly to the prosecutor’s office at the Sincan courthouse.

The finding of the GPS device was mentioned in the indictment concerning the events at Akıncı Air Base, but the prosecutor left a key detail out of the indictment that was later discovered during the trial. The bombshell revelation was announced by Lt. Özay Cödel during a hearing held at the Ankara 4th High Criminal Court on July 17, 2018. “Adil Öksüz, who was captured with a GPS device registered to MIT inventory, mysteriously escaped or was made to disappear,” he testified in court. Cödel was with Öksüz at the gendarmerie station.

According to a document dated July 18 and signed by gendarmerie district commander Murat Bozdağan, Öksüz came to the station after his release by the judge at the arraignment hearing at 06:32 hours on July 18. He retrieved all his possessions that were seized when he was detained and signed a document confirming that he had received all his belongings.

This was quite odd and in fact against the Code of Criminal Procedure. Belongings such as mobile phones and GPS devices were supposed to be examined by experts under a court ruling and submitted as evidence in the case file. No such procedures were ever applied to Öksüz, who apparently received special treatment in contrast to the others who were detained along with him.

During his detention at the gendarmerie station in the Kazan district of Ankara on July 17, Öksüz received a special visitor from the Prime Ministry’s office. Ali İhsan Sarıkoca, a senior government official who worked as an advisor in the Office of the Prime Ministry, took the trouble to visit him during the mayhem. Sarıkoca was one of Erdoğan’s most trusted aides and had been with him since the 1990s. He has managed the Prime Ministry Communications Center (BİMER), a crucial post that handles complaints, tips and intelligence and helps prosecute government critics using information conveyed through hot line, often anonymously.

Sarıkoca used a police intelligence officer named Sertel Koçak to gain access to Öksüz in detention and managed to free Öksüz. Sarıkoca’s phone records showed he talked to the police officer 27 times between July 14 and 22. The records also exposed the lies in Sarıkoca’s statement because the cell tower signals did not match the locations where he claimed to have been.

According to witnesses, Sarıkoca spoke with Öksüz in Arabic, possibly to prevent others from eavesdropping on their conversation. The unusual visit added more credibility to the claims that Öksüz was in fact working for the government.

According to witness accounts, Öksüz was also spared severe beating and torture at the station while everybody else was punched, kicked and beaten by police. Hasan Alp Koruyucu, a first sergeant, testified at the Ankara 4th Criminal Court on July 19, 2018 that he was with Öksüz in detention. The police already knew him as an imam affiliated with the Gülen movement but did not touch him.

Another witness, Mete Kılıçarslan, a first sergeant with the Special Forces Command, testified at the Ankara 17th High Criminal Court on November 14, 2017 that he and others were beaten severely but that the police did not touch Öksüz despite the discovery of the GPS locater locater in his possession.

Öksüz was then moved to the Sincan courthouse from the Kazan gendarmerie station and put in a holding cell along with dozens of military officers. While they were waiting, gendarmerie first sergeant Osman Gök came and ordered Sgt. Serkan Çoraplı to give Öksüz his cell phone, which was kept in the evidence bag. Öksüz had two phones, an Android and an iPhone. He did not want to use the phone handed to him by the sergeant, instead asking for his second phone, also kept in the bag, and got it.

He made a call at 15:09 hours on an app, rather than a direct call, to prevent any trace of whom he talked to. His conversation lasted for five minutes. Witnesses said he was speaking in a very low voice on the phone. It was never discovered whom he called and what he talked about for five minutes.

His cellmates in the holding cell also asked for their phones to make calls to their lawyers and family members, but their requests were denied. Instead, gendarmes told them that they could use Öksüz’s phone if he was OK with it. Several people used the phone, but they were later slapped with accusations that they actually knew Öksüz and were associated with him.

One of the officers who used the phone was Halil Burak Balcı, who called his father Hasan Balcı to ask him to retain a lawyer. Mesut Güney called his wife on the same phone. Because of the phone call, Balcı’s father was later arrested for receiving a call from Öksüz’s phone, jailed and charged with involvement in a coup against the government. He repeatedly said he was innocent, had nothing to do with Öksüz and explained that his son used Öksüz’s phone in detention to contact him.

During the trial several defendants asked the court to issue a ruling to obtain the CCTV footage from the Sincan courthouse between July 16 and 17, 2016 during which time Öksüz made a phone call. The court granted their request in September 2017. However, deputy chief prosecutor Ergün Şahin informed the court that the CCTV footage had been destroyed and could not be retrieved.

Öksüz’s movements after his release paint a picture of a man who had nothing to worry about. He was not in a hurry to go into hiding. He even booked a ticket under his name on July 18 and flew to Istanbul on national flag carrier Turkish Airlines (THY), even though he knew all THY bookings and flight information were monitored by MIT in real time. He stayed in Istanbul for a while and then decided to visit his in-laws in Sakarya. His travels abroad since 2014 also showed that he used THY as his carrier of choice.

It was also interesting that Öksüz had been the subject of investigations since 2014 and that a surveillance order was issued for him in 2015. He was identified early on as a man who allegedly coordinated the Gülen group’s links to the Turkish military, yet he remained free, traveling in Turkey and abroad with no difficulty. His movements lend further credence to the claim that he was a MIT agent. Öksüz went to the US on July 11 and came back a day later to bolster the government narrative that he took orders from Gülen to start the coup. Gülen denied the allegations.

More interesting facts emerged about MIT’s complicity in the coup with respect to Öksüz during the investigation. According to the testimony of public safety intelligence officer Ahmet Camgöz, who was working at the Kazan district gendarmerie station, a patrol spotted a black Honda CR-V sedan with four passengers that was parked on the side of the road near Akinci Air Base, the alleged headquarters of the putschists, around noon on July 16. The patrol approached the car to investigate.

“There were four people in the vehicle with the driver. The driver exited the vehicle and showed his ID, saying, ‘Take it easy.’ He had a MIT badge. When we saw that the badge was from MIT, we let them go,” Camgöz told the court. Öksüz was reportedly detained near that place on July 16.

Kubilay Selçuk, a major general and a fighter pilot, told the court on February 26, 2019 that it was incomprehensible that Öksüz, who faced a fresh arrest warrant after his release, couldn’t be found, when troops specially trained in evasion, infiltration and camouflage tactics were arrested. Questioning why Öksüz was not named as a member of the Peace at Home Council, a central committee that allegedly organized the coup attempt, Selçuk said, “If Adil Öksüz was in custody, this fabricated, fictional council would not have been in the indictment, parts of the puzzle would have been put in place, the plotters would have been discovered and the barrier [around coup cases] could not have been built.”

By: Abdullah Bozkurt

Source: Nordic Monitor