Joe Biden fulfilled a campaign promise on 24 April, one that several of his predecessors had demurred on, when he recognised the Armenian genocide of 1915.

In a carefully worded statement, released on the anniversary of the tragic events, Biden acknowledged the Armenians who were “deported, massacred, or marched to their deaths in a campaign of extermination” in eastern Anatolia, in what is now Turkey.

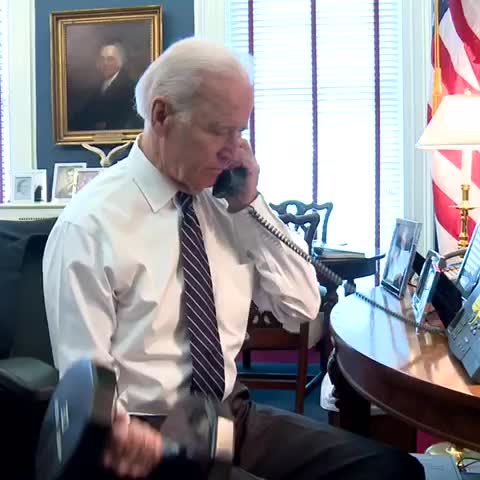

Biden’s announcement came the day after he first made phone contact with Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Presumably Erdoğan was pleased that Biden had finally got in touch; clearly, he is less enamoured of Biden’s genocide statement.

Turkey emphatically denies the events of 1915 were a genocide and has spent decades attempting to forestall any US presidential recognition of them as such. Speaking to a Turkish audience, Erdoğan declared that Biden’s statement was “unfounded and unfair” and would put US-Turkey relations on a difficult road. Turkey’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs called it a “gross distortion of history”.

It seems that some in Turkey harbour reservations about Biden.

The Biden phone call to Erdoğan had been a long time coming. It is customary for newly incumbent US presidents to contact world leaders. To whom and in what order they make calls is indicative of foreign policy priorities and how strongly the US values their bilateral relationships.

It is telling that Biden had not sought out Erdoğan until last week. As a long-standing US ally, Turkey would expect to be near the top of Biden’s telephone list. By this time in his presidency, Barack Obama had not only called Erdoğan but, in a nod to a government then seen as an exemplar of democracy in the Islamic world, had also addressed the Turkish parliament. Donald Trump apparently spoke to Erdoğan with some regularity and applauded his strong-man persona.

All of which meant there was consternation in Ankara that Biden took so long to get in touch. The somewhat jilted, state-run Anadolu Agency recently reported that a somewhat non-committal White House said it would call “at some point.” US-based Turkey analyst Soner Çagaptay quipped that Erdoğan should expect a call just before Turkmenistan, as Biden worked through his phone book alphabetically.

The US-Turkey relationship is based on strategic interests. Turkey has long been a pillar of NATO and, employing a woefully overused metaphor, is seen as the West’s bridge to the Middle East. There has often also been a personal element to the relationship. Erdoğan forged a connection with Trump, while playing the US off against Russia and convincing Trump to green-light Turkey’s 2019 incursion into north-eastern Syria, an area controlled by America’s allies, the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Trump was widely criticised for being outfoxed by Erdoğan and abandoning the mainly Kurdish Syrian militias that had battled so doggedly against ISIS.

Biden will not be such a pushover. He is clearly taking a new approach to Turkey. It is not entirely unexpected that he initially gave Erdoğan the cold shoulder. In a 2020 interview, he expressed misgivings about Turkey’s increasingly adventurist foreign policy and about Erdoğan, calling the Turkish president an “autocrat”. More recently, Biden decried as “deeply disappointing” Erdogan’s unilateral decision to withdraw from Europe’s Istanbul Convention, which protects women’s rights.

The sudden withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention is indicative of Turkey’s ongoing authoritarian drift. Erdogan was once considered a champion of political reform, hence Obama’s 2009 visit to Ankara. However, having accumulated more power through a new presidential model of his own design, Erdoğan has steadily grown more sensitive to criticism and more repressive.

In March, Erdoğan announced a new Human Rights Action Plan, to be implemented by 2023, the Republic of Turkey’s centenary, but a US State Department report indicates that human rights and political freedoms are actually deteriorating. Biden is no doubt aware of this.

Meanwhile, it seems that some in Turkey harbour reservations about Biden. TRT, the state broadcaster, while highlighting Biden as prone to “gaffes” also decried his “misguided views” on the Kurds. Biden, in fact, has a long relationship with Kurdish communities across the Middle East, such that some expect him to be the most pro-Kurdish president ever.

The Kurds occupy a notoriously fraught position in Turkey’s politics. Several recent court cases brought against the Peoples’ Democracy Party, which wins the vote of many of Turkey’s Kurds, highlight this and are yet more examples of democratic backsliding. If Biden really is pro-Kurdish, it may well create another bump in the road of US-Turkey relations.

Erdoğan told the congress of his Justice and Development Party in March that Turkey intends to “increase the number of our friends and resolve hostilities in the region”. To achieve this, reconciliation between Turks, Kurds and Armenians would be a good start. Despite getting off on the wrong foot, perhaps Biden is just the president who can help make this a reality.

By: William Gourlay – a Research Associate at the Middle East Studies Forum at Deakin University and is the author of The Kurds in Erdogan’s Turkey (Edinburgh University Press).

Source: Lowy Institute