On March 17, 2021, a top prosecutor at Turkey’s Court of Cassation filed a case with the Constitutional Court demanding the closure of the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP), which is currently the third-largest party in the parliament. This move came as no surprise to those who are in the know about Turkey’s long history of shutting down political parties deemed to “threaten national unity and integrity.”

It was also no surprise for those following closely the statements by the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) ultra-nationalist ally Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) politicians. Just a month before the prosecutor filed the closure case, on February 16, 2021, the leader of the MHP, Devlet Bahçeli, said, in his party’s weekly meeting, that “it is imperative that the HDP should be closed. I believe that the Court of Cassation’s office of Chief Public Prosecutor will do what is required.”

When on March 31, 2021 the Constitutional Court returned the indictment to the Court of Cassation, citing procedural deficiencies as a reason, Bahçeli stroke back: “In addition to the closure of the HDP, the closure of the Constitutional Court shall also be an aim that cannot be postponed.”

Meanwhile, at a TV program aired on March 14, Yasin Aktay, the chief consultant to the ruling AKP’s leader, uttered that “all the necessary conditions for HDP’s closure are now ripe. Its non-closure is now a reason for public outrage.”

Islam as a Unifying Force?

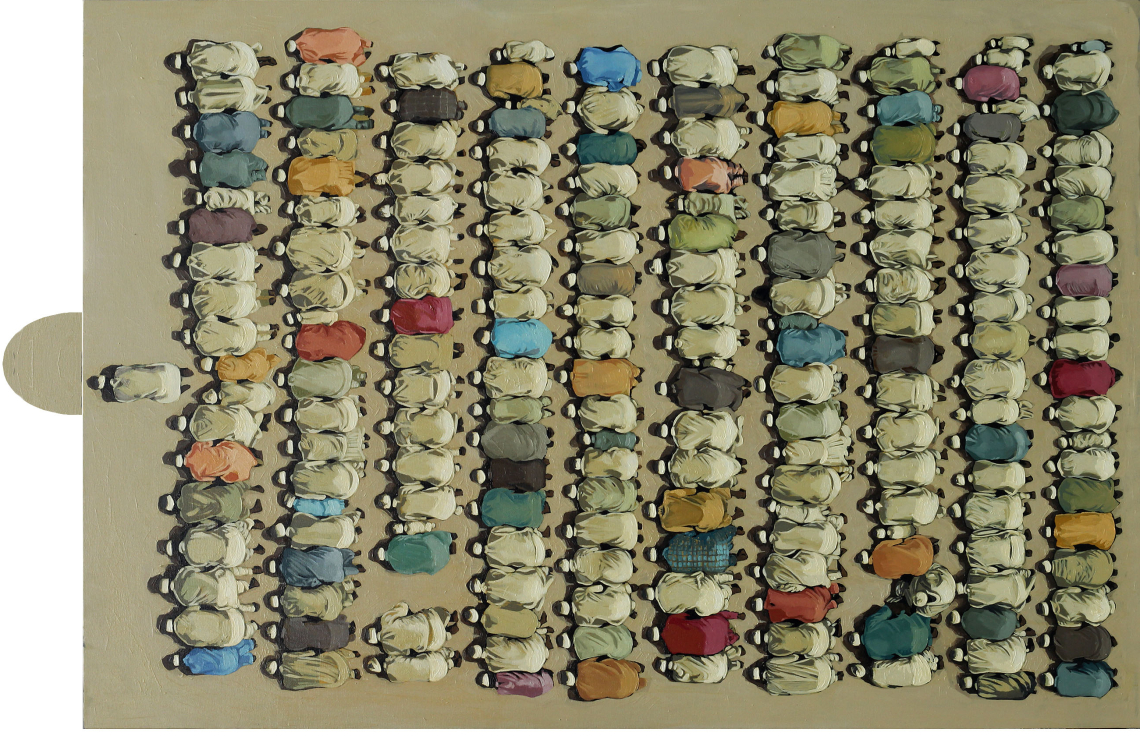

Things have not always been as rocky between the AKP and the Kurdish movement. Before the AKP allied with the MHP in 2016, it was involved in peace talks with the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has led an armed struggle for Kurdish independence (and later for autonomy) against the Turkish Armed Forces since the late 1970s. During the peace process that began in 2012 and ended in the summer of 2015, both sides presented Sunni Islam as a conflict resolution tool, a unifying supranational identity that could bridge the ethnic divide between the Sunni-majority Turks and Kurds.

Historically, different governments in Turkey resorted to religion to subdue Kurdish nationalism. However, none had advocated “Muslim fraternity” as strongly as the AKP governments have. Moreover, never before did the secular PKK, with Marxist origins, display as positive a stance towards Islam as it did during the AKP rule. Especially in 2012 and 2013, the role of religion became so pronounced in the conflict that both Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, then prime minister, and Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned leader of the PKK, went on to cite the same Qur’anic verses and hadiths [Prophet Muhammad’s sayings] to emphasize “Muslim unity and solidarity.”

Limits of Muslim Unity

Yet, in June 2015, the ceasefire was broken, clashes between the Turkish Armed Forces and the PKK have resumed, thousands of people have died, and thousands have been internally displaced.

Against this background, in my book Under the Banner of Islam: Turks, Kurds, and the Limits of Religious Unity, I focus on the ambivalent role Sunni Islam has played in Turkey’s Kurdish conflict, both as a tool of assimilation and as a tool of resistance, and I inquire why “Muslim fraternity” has not resonated well among Sunni Turks and Kurds.

Using the Kurdish case as an opportunity to explore the relationship between religion, ethnicity, and nationalism, I scrutinize the role of religion in ethnic conflicts and ask: Is it possible for religion to act as a conflict resolution tool? Why? Why not?

In search for answers to these questions, I take the reader on a journey into the inner circles of religious elites from different backgrounds: non-state appointed local Kurdish meles, state-appointed Kurdish and Turkish imams, heads of religious NGOs, members of religious orders (tariqahs), and pious politicians.

Relying mainly on participant observation in Friday prayers, systematic analysis of newspapers, and 62 interviews conducted over the course of a year (between June 2012 and June 2013) in three different cities (İstanbul and the majority-Kurdish Diyarbakir and Batman), I argue that the different conceptualizations of ethnic and religious identities by Sunni Muslim Turkish and Kurdish elites play an important role in preventing their unification under the umbrella of Sunni Islam. In doing so, I develop the concept of “religio-ethnic” identity and put forward a four-fold typology capturing the convergence and divergence of religious and ethnic identities, as conceptualized by Kurdish and Turkish religious and political elites: 1) Ethno-religious; 2) Religio-ethnic; 3) Religious; 4) Secular.

While some of my interviewees clearly distinguish between ethnicity (as a secular identity) and religion (as a supranational identity overarching ethnic differences), some (mostly Kurdish religious elites) claim that religious and ethnic identities are inseparable in that ethnicity is God-given; they deem the existence of different ethnic identities as God’s will. In this, they substitute to what I call a “religio-ethnic” identity. Yet many Sunni Turkish elites display an “ethno-religious” approach that prioritizes Turkish identity and sees Turks as “the leaders of the Muslim ummah.” For them, ethnicity and religion are interwoven but separable, as ethnicity trumps religious identity; what matters is not Islam per se but Turkish Islam.

Beyond Identity

Although the different conceptualizations of ethnic and religious identities prevent the unification under the umbrella of Sunni Islam, it would be misleading to claim that it is the only reason that has hindered the deployment of religion as a peacemaker in Turkey’s Kurdish conflict.

As identity categories do not exist in a vacuum and are historically and politically grounded, I contend that related structural factors should also be taken into consideration when discussing this issue. The Syrian civil war, especially the establishment of an autonomous Kurdish region—Rojava—in Northern Syria, as well as the non-transparent nature of the peace talks and the continuous mistrust between the government and the Kurdish movement are among the factors that contributed to the termination of the peace process in the summer of 2015. In such an environment, it was quite hard for Sunni Islam to act as the “cement” it was envisioned to be.

While Under the Banner of Islam is a story of religion, ethnicity, and nationalism in Turkey’s Kurdish conflict, it is also a story of how ethnic and religious identities are negotiated in conflict resolution and how symbolic boundaries are drawn in ethnic conflict zones. I hope it will serve well students, academics, lay readers, and policy-makers who would like to learn more about religion, ethnicity, nationalism, and conflict, in general, and about the evolving role of Islam in contemporary Turkey and in the Kurdish conflict, in particular.

***

By: Gülay Türkmen – a sociologist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Graz’s Center for Southeast European Studies. Her work examines how macro-scale historical, cultural and political developments inform questions of belonging and identity-formation in multi-ethnic and multi-religious societies. She is the author of Under the Banner of Islam? Turks, Kurds and the Limits of Religious Unity (Oxford University Press, 2021). She has published in several academic outlets including the Annual Review of Sociology, Qualitative Sociology, Sociological Quarterly, Nations and Nationalism, and New Diversities. Follow her on Twitter at @gulayturkmen

Source: Siyasa