The abiding image of the Iraq war in 2003 was the toppling of a statue of the country’s dictator, Saddam Hussein. It was an image relayed across the world as a symbol of victory for the American-led coalition, and liberation for the Iraqi people. But was that the truth? Putting up a statue is an attempt to create a story about history. During the invasion of Iraq, the pulling down of a statue was also an attempt to create a story about history. The story of Saddam’s statue shows both the possibilities, and the limits, of making a myth.

Operation Iraqi Freedom, as it was called by those running it, began on 20 March 2003. It was led by the US at the head of a “coalition of the willing”, including troops from Australia, Poland and the UK. President George W Bush claimed that the aims of the operation were clear: “to disarm Iraq of weapons of mass destruction, to end Saddam Hussein’s support for terrorism, and to free the Iraqi people”. He continued: “The people of the United States and our friends and allies will not live at the mercy of an outlaw regime that threatens the peace with weapons of mass murder … It is a fight for the security of our nation and the peace of the world, and we will accept no outcome but victory.” This justification for war was hotly disputed at the time, and has been ever since.

Invading troops moved quickly through the country. They arrived at Baghdad on 7 April, two and a half weeks into the ground campaign. It was there that the statue of Saddam stood in Firdos Square (firdos meaning paradise), right in the centre of the city. Two days later, it would come crashing down.

In 2020, statues across the world were pulled down in an extraordinary wave of iconoclasm. There had been such waves before – during the English Reformation, the French Revolution, the fall of the Soviet Union and so on – but the 2020 iconoclasm was global. Across former imperial powers and their former colonial possessions, from the US and the UK to Canada, South Africa, the Caribbean, India, Bangladesh and New Zealand, Black Lives Matter protesters defaced and hauled down statues of slaveholders, Confederates and imperialists.

Edward Colston was hurled into the harbour in Bristol, England. Robert E Lee was covered in graffiti in Richmond, Virginia. Christopher Columbus was toppled in Minnesota, beheaded in Massachusetts, and thrown into a lake in Virginia. King Leopold II of the Belgians was set on fire in Antwerp and doused in red paint in Ghent. Winston Churchill was daubed with the words “is a racist” in London.

Some feared that this was becoming a frenzy. In the US, Confederate statues had long been a focus for public protest, but soon statues of national icons and progressive figures were attacked too. Protesters in Madison, Wisconsin, tore down the Forward statue, celebrating women’s rights, and one of an abolitionist. A statue of the abolitionist Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York, was knocked clean off its base. It was unclear whether the perpetrators were confused antifascists or fascists, retaliating for the removal of Confederates and slaveholders.

The backlash was led by President Donald Trump, who signed an executive order declaring: “Many of the rioters, arsonists, and left-wing extremists who have carried out and supported these acts have explicitly identified themselves with ideologies – such as Marxism – that call for the destruction of the United States system of government.” The order reiterated that those who damage federal property could face 10 years in jail.

Boris Johnson, the British prime minister, said on Twitter that “those statues teach us about our past, with all its faults. To tear them down would be to lie about our history, and impoverish the education of generations to come.” The Conservative government announced that it would amend the Criminal Damage Act so anyone damaging a war memorial in Britain could also be looking at 10 years in prison.

Museums and civic authorities were quick to react, too, though often in a different way. The day after the slave trader Colston’s statue was pulled down, the Museum of London Docklands removed its own statue of another slave trader, Robert Milligan.

In the US and UK, rightwing Republican and Conservative administrations took the opportunity to position themselves as the champions of American and British civilisation: the last defence against barbarism and “political correctness”. In September 2020, the British culture secretary, Oliver Dowden, wrote to museums, threatening them with funding cuts if they took any actions “motivated by activism or politics”.

On the face of it, the attacks on statues in 2020 followed a pattern: those who cheered on the protesters pulling them down tended to be younger and more socially liberal, while those who were dismayed by the destruction tended to be older and more conservative.

If you look more deeply into it, though, the issue of statues is far more complicated. When statues of Lenin were pulled down across Ukraine in 2014, and when the Firdos Square statue of Saddam Hussein was pulled down in Iraq in 2003, many older western conservatives rejoiced; some younger progressives were less sure about celebrating. When the Islamic State destroyed ancient statues in Palmyra in 2015, there was condemnation across the political spectrum. Many of those responding to these events were the same people who responded very differently later when statues of Confederates and slaveholders were the focus. Statues are not neutral, and do not exist in vacuums. Our reactions to them depend on who they commemorate, who put them up, who defends them, who pulls them down, and why.

Saddam Hussein joined the Ba’ath party at the age of 20 and, in the next two decades, rose through the party, seizing power in 1979. His ambition was great: to assert leadership of the Arab world and control the Persian Gulf. He invaded Iran’s oilfields in 1980, leading to a long, expensive and destructive war. He invaded Kuwait in 1990, earning the condemnation of the United Nations.

In January 1991, there was a military response from an international coalition led by the US, including Egypt, France, Saudi Arabia and the UK. In what became known as the first Gulf war, Saddam was forced out of Kuwait. Internationally, Iraq was humiliated. Northern and southern sections of the country were declared “no-fly zones” where the air traffic was policed by American, British and French forces. The country was slapped with ruinous sanctions and was banned from developing nuclear, chemical or biological weapons. Internally, it was stricken with rebellions, notably by Shia and Kurdish groups. Saddam put these down brutally.

As president, Saddam had modelled himself partially on Joseph Stalin. Both were peasant outsiders who, with exceptional ruthlessness, had made their way to the top. Saddam imitated Stalin’s style of propaganda, promoting images of himself smiling and enriching the Iraqi people: a benevolent uncle. He even grew a similar moustache. Like Stalin, he also raised vast numbers of statues to himself.

Many Islamic traditions ban the representation of human figures, particularly religious figures. In terms of Iraqi history, though, Islam is a relatively recent arrival. Mesopotamia, as the region was once known, has ancient and glorious traditions of art, including statuary, stretching back thousands of years. Representations of figures are deeply embedded in Mesopotamian culture: there could be no ban on them. Under Saddam’s rule, it was possible – even necessary – to make images of him. All schools, public buildings and businesses had to display his portrait.

Saddam’s iconography was a distinctive blend of military swagger and historical references. Some of his equestrian statues depicted him with sword drawn, pointed in the direction of Jerusalem: his rearing horse was flanked by rockets. He was occasionally sculpted wearing the Dome of the Rock on his head, the Islamic shrine refashioned as a helmet. His images used costume and props to link him to Hammurabi, the Babylonian lawgiver; Nebuchadnezzar, enslaver of the Jewish people; various caliphs; Saladin, the defeater of Christian crusaders (who, like Saddam, had been born in Tikrit); and even Muhammad himself. The essence of all these historical figures was supposedly distilled down into Saddam, uniting the Iraqi people and Mesopotamian history, reaching out across the whole Middle East.

After the Gulf war in 1991, sanctions imposed by the international community banned all trade with Iraq except in humanitarian circumstances. Among many hardships, this made it difficult for artists and sculptors to access materials. One way to get paint, canvas, bronze and stone was to paint pictures or make sculptures of Saddam. If the art was right, the regime would provide. While the Iraqi people suffered under sanctions, Saddam built vast palaces filled with monuments to himself. It is unclear how many statues of himself Saddam put up in this period, though there were hundreds in Baghdad alone.

There was nothing special about the statue of Saddam that was put up in Firdos Square in April 2002 to mark his 65th birthday. Firdos Square is not the most important location in Baghdad, and the statue was unexceptional: a bronze standing figure, 12 metres high, weighing around a tonne. The fact that it was not a big deal may be one reason why, since its destruction, there has been confusion as to who made it.

At least two different sculptors have been credited with creating this statue, with two different narratives. This is characteristic of the story of Saddam’s statue in Firdos Square. The boundary between what is real and what is fake would soon disappear altogether.

The French philosopher Jean Baudrillard defined hyperreality as a state in which you cannot tell the difference between reality and a simulation of reality. In 1991, at the time of the first Gulf war, he wrote three essays touching on this theme, later published together as The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Baudrillard argued that the relevant events in the first couple of months of 1991 were not really a war, in the sense that “war” was commonly understood: they were a simulation of a war.

There were two reasons for this. First, the events were carefully choreographed through the media: the coalition military controlled which images could be shown, and which journalists were allowed to report. The television-watching public audience in the west was shown non-stop video footage of firework-like bombings, and point-of-view shots of missiles heading to their targets.

The effect was that of playing a computer game: clean, surgical, without consequences. Second, Baudrillard argued, the outcome of the war was never really in doubt: it was “won in advance”. The coalition was always going to win, and Saddam, for all his posturing, was in no position to fight back. This simulated war was “stripped of its passions, its phantasms, its finery, its veils, its violence, its images: war stripped bare by its technicians even, and then reclothed by them with all the artifices of electronics, as though with a second skin”.

The hyperreality of the Gulf war that Baudrillard described caught the imaginations of writers, artists and film-makers. It looked ever more prescient as the internet began to connect the world. Excitement and anxieties about real versus virtual experiences grew. A hyperreal war was played out in the 1997 political comedy film Wag the Dog (loosely based on a 1993 novel), in which an American president creates a fictional war abroad to distract from a sex scandal at home. Hyperreality was the basis of the 1999 action science-fiction blockbuster The Matrix. The character Morpheus is quoting Baudrillard when he says: “Welcome to the desert of the real.”

In 2003, when US-led forces launched Operation Iraqi Freedom and invaded Iraq, the situation would be different. This war would be fought both in “the desert of the real” and in the real desert. A ground invasion was the focus. Resistance was put up by Iraqi forces, and territory was occupied by the coalition, though this war, too, was effectively “won in advance”.

Iraqi spokesman Mohammed Saeed al-Sahaf’s lively press briefings claimed that Saddam was winning, but it was pretty easy to tell that his attempt to create a simulation of victory was not reality. “Baghdad is safe. The battle is still going on. Their infidels are committing suicide by the hundreds on the gates of Baghdad. Don’t believe those liars,” he told international camera crews on the roof of the Palestine Hotel. Behind him, viewers could see Iraqi troops fleeing from American tanks on the other side of the river. Al-Sahaf became something of a celebrity, nicknamed Comical Ali (a play on Chemical Ali, Saddam’s intelligence chief Ali Hassan al-Majid, who had ordered the use of chemical weapons against the Kurds in the 1980s).

Bringing down Saddam’s statue was a greater feat of hyperreality. It would be presented to the world as a climax: the triumph of Operation Iraqi Freedom. The coalition forces were cast as liberators, allowing the Iraqi people to rise up at last and tear down the most powerful symbol of the dictator who had oppressed them. But the reality was not so simple.

Since they had invaded Iraq on 20 March, coalition forces had been pulling down dozens of statues of Saddam. For example, on 29 March, British forces had blown up a cast-iron statue of him in Basra. “The purpose of that is psychological,” said a military spokesperson, “to show the people … he does not wield influence, and we will strike at any representative token of that eroding influence”. But no one filmed this event, so – while it was reported by the BBC and other news organisations – it made little impact outside Basra itself.

On 7 April, the day that the fall of Baghdad began, US soldiers seized the Republican Palace. Their commander ordered his troops to find a statue that could be destroyed, and to wait until Fox News arrived before they began to destroy it. Soon enough, they found an equestrian statue of Saddam. The television crew turned up, and the soldiers duly fired a shell. The footage was not exciting – just Americans destroying stuff, no crowd of grateful Iraqis – so it did not get much play. That same day, US Marines and Iraqi civilians brought down another Saddam statue in Karbala. The next day, British troops took out another one in Basra. There were so many statues of Saddam in Iraq that they were being felled on a daily basis.

A number of international journalists who were covering the invasion moved into the Palestine Hotel on Firdos Square, where Mohammed Saeed al-Sahaf held his amusing press conferences. They had been relocated from the Al Rasheed Hotel, closer to the city’s political centre, after much of it had been destroyed by bombing. Though the Palestine Hotel was known to be a media refuge, an American tank fired a shell at it on 8 April, mistaking a camera on a balcony for an Iraqi spotting device. Two journalists were killed, three were injured, and the rest were outraged.

It was fortunate, then, that a story would come along to distract them from their anger at the Pentagon the next day, and that it would happen on Firdos Square – right outside their hotel. Fortunate, but not planned by the Pentagon. The story was created spontaneously by American soldiers on the ground. It was spun into a full-blown global event by the international news media.

On 9 April 2003, Lt Col Brian McCoy, in charge of the 3rd Battalion 4th Marines, was told by a journalist at the Palestine Hotel that there were no Iraqi forces in Firdos Square. Simon Robinson, a reporter for Time magazine, said McCoy knew that journalists would be there, so “there were going to be opportunities”.

Capt Bryan Lewis, leader of McCoy’s tank company, blocked the streets leading to the square. Gunnery Sgt Leon Lambert, in an M-88 armoured recovery vehicle, radioed him with an idea: should they pull down Saddam’s statue? Lewis replied: “No way.”

McCoy went into the Palestine Hotel to meet reporters. Just after 5pm, Lambert radioed Lewis again, telling him that now local Iraqis themselves wanted to pull down the statue. There were a few of them in the square, and a lot of journalists.

Lambert’s claim that some Iraqis wanted to pull down the statue is corroborated to some extent by Kadhim Sharif Hassan al-Jabouri, a local mechanic. Kadhim claimed that he had once fixed motorcycles for Saddam and his son Uday, but there had been a dispute over money. Uday had him thrown in prison. “Fourteen or 15 people in my own family were executed by Saddam,” Kadhim told the BBC. When he heard American forces were coming, he was happy. He says he took his sledgehammer and left his nearby garage to go to Firdos Square.

Lambert asked Lewis: “If a sledgehammer and rope fell off the 88, would you mind?”

“I wouldn’t mind,” Lewis replied. “But don’t use the 88.”

Lambert says he gave the Iraqis his sledgehammer, though Kadhim claims to have brought his own. It is unclear, then, whether the idea to attack the statue came from a relatively low-ranking US soldier, from an Iraqi civilian, or from both.

Kadhim began to hammer at the statue, but all he could really do was get a couple of plaques off the base. Lambert’s rope was thrown around the statue’s neck. There was little chance of this small crowd toppling such a large bronze. An hour went by.

Saddam was not budging. “We watched them with the rope, and I knew that was never going to happen,” Lambert told journalist Peter Maass, who wrote a detailed investigation of the felling of the statue in 2011. “They were never going to get it down.”

At this point, the handful of Iraqis having a go at the statue seemed inclined to give up and go home. Just then, McCoy came out of the hotel. “I realised this was a big deal,” he said. “You’ve got all the press out there and everybody is liquored up on the moment. You have this Paris 1944 feel. I remember thinking, the media is watching the Iraqis trying to topple this icon of Saddam Hussein. Let’s give them a hand.”

McCoy radioed a senior officer, who authorised him to involve troops directly in pulling down the statue. McCoy told his troops they could use the M-88 recovery vehicle after all, providing there were no fatalities.

Around 6.50pm the M-88 drove away from the statue, dragging it face forward with the chain around its neck. Slowly, the bronze bent forward at the knee and ankle, Saddam’s huge figure bobbing for a few seconds in a horizontal position as the modest crowd of Iraqis whistled and cheered. Finally, the statue snapped off its plinth, leaving its feet behind. Iraqis ran forward, jumped on it and danced. It was crushed to pieces.

That morning, photojournalist Patrick Baz had been in Saddam City (a neighbourhood of Baghdad later renamed Sadr City). There, he had seen an Iraqi man who had pulled down a different Saddam statue. It was tied to the back of his car with a cable.

Whenever the man saw a group of people, he would stop. They would all crowd around Saddam and start hitting him with their shoes. (Shoes are considered dirty in the Middle East: it is rude to show someone the soles of your shoes, and a terrible insult to hit them with a shoe. In 2008, an Iraqi journalist would make international news when he threw a shoe at George W Bush.)

“The image was all the more strong because there wasn’t an American soldier in sight,” Baz later wrote. “Just the locals expressing what they felt about their country’s long-term dictator.” Baz hurried back to his room at the Palestine Hotel to send his pictures to his editors, then heard a commotion outside and witnessed the Firdos Square toppling. Only one of the Saddam topplings made the front pages, and it was not the one that Iraqis had done for themselves. There was a real story here about pulling down a statue in Saddam City. The world’s media preferred the simulation in Firdos Square.

As two hours of non-stop coverage of Firdos Square was beamed around the world that night, the news networks desperately wanted it to have a meaning. Wolf Blitzer of CNN described the footage as “the image that sums up the day and, in many ways, the war itself”. Over on Fox, the anchors agreed. “This transcends anything I’ve ever seen,” said Brit Hume. His colleague agreed: “The important story of the day is this historic shot you are looking at, a noose around the neck of Saddam, put there by the people of Baghdad.” But it was an American rope, put there by American soldiers.

Between 11am and 8pm on 9 April, Fox News replayed the footage of Saddam’s statue coming down every 4.4 minutes. CNN replayed it every 7.5 minutes. The coverage of Firdos Square – which heavily implied that the statue had been pulled down by a large crowd of cheering Iraqis – suggested that the war was over. The hated dictator was symbolically ousted when his statue fell. In reality, it was not the end. The fighting was still going on. Armed engagements were underway in Baghdad and northern Iraq while the pageant was proceeding in Firdos Square.

Saddam would not be captured for another seven months. Stories abounded that he had body doubles: a German TV show suggested in 2002 that there were at least three of them. An Iraqi doctor claimed that the real Saddam had died in 1999 and had been played by doubles ever since. The Dutch researcher Florian Göttke wrote: “Saddam had already multiplied his body and extended his presence throughout the country through his statues, and by the same token, by living through the multiple living bodies of his doppelgängers he would become more than human, he would extend his presence into the realm of myth – he would even be able to survive his own assassination.”

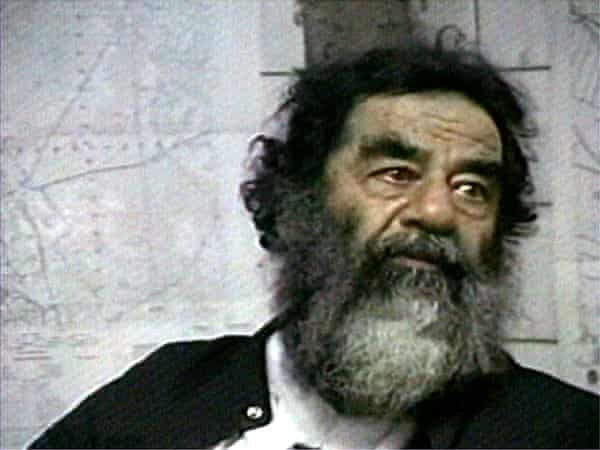

Saddam’s omnipotence was an illusion, too. When the real Saddam was dragged out of the hole he had been hiding in, it was like the moment in The Wizard of Oz when the curtain is pulled back. Suddenly everyone can see that the Wizard is not some all-powerful demigod, but an ordinary little man who has made his own myth. The real Saddam – scruffy, hairy and wizened – was a world away from the proud statues showing him astride rocket-powered horses.

At the time, the fall of the Firdos Square statue was presented as a satisfying end to the story of the invasion of Iraq. In the weeks after it came down, coverage of the Iraq war on Fox News and CNN decreased by 70%.

On 1 May 2003, Bush stood on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln, nowhere near Iraq but safely off the coast of San Diego. He delivered a speech announcing that major operations in Iraq had ceased. It was, he said, in front of a giant Stars and Stripes banner repeating the message: “Mission accomplished”. (There was a historical echo here of Joe Rosenthal’s iconic shot of US Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima in February 1945. The photograph was widely assumed to signify that victory in the Pacific was imminent: in fact, the Battle of Iwo Jima would go on for another month, and three of the six Marines in the picture would die in it. The war in the Pacific did not end until September 1945.)

Baudrillard’s argument that the 1991 Gulf war did not take place was not an exact fit for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. But the end of that war, as signified by pulling down the statue of Saddam in Firdos Square, was a perfect Baudrillardian simulation. The media turned an impromptu performance by a few American soldiers into a highly convincing television series finale in which the Iraqi people defeated their dictator. It was repeated in broadcasts and newspapers across the world. It was not true.

For those troops fighting the war, and those civilians living through it, the war had only just begun. The coalition had no plan for how to end it: no coherent vision of the Iraq they wanted to emerge. Saddam would be tried and hanged at the end of 2006.

American troops would remain in Baghdad until 21 October 2011, eight-and-a-half years after the statue toppling. Thousands of coalition soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis would die.

After the troops left, Iraq remained divided, damaged and unstable. In 2014, American soldiers would return to take on the threat posed by Isis, which had emerged from the wreckage to make things even worse.

“Now, when I go past that statue, I feel pain and shame,” said Kadhim al-Jabouri in 2016. “I ask myself”: Why did I topple that statue?” He regretted the fall of Saddam’s regime. What came after, in his opinion, was a disaster: “Saddam has gone, but in his place we now have one thousand Saddams.” Kadhim even wanted the statue back. “I’d like to put it back up, to rebuild it,” he said. “But I’m afraid I’d be killed.”

In the state of hyperreality, it is impossible to tell the difference between reality and a simulation of reality. The thing about reality, though, is that it continues to evolve. Sooner or later, the simulation begins to glitch, then ultimately falls apart.

by Alex von Tunzelmann

This is an edited extract from Fallen Idols: Twelve Statues That Made History by Alex von Tunzelmann, published by Headline on 8 July and available at guardianbookshop.com

Source: Guardian