Five months after the terrorist strikes by al-Qaida on 11 September 2001, a lawyer named Ron Motley received a phone call from Deena Burnett, whose husband had been killed in the attack. Thomas Burnett, she explained, had been on one of the hijacked planes. She wanted to ask whether he would help her to find a way to sue those responsible for the attack that claimed her husband.

Two weeks after the call, on 2 March 2002, Motley and a team of lawyers with his firm, Motley Rice, spent a day with the Burnett family at their home in California. They described how, upon realising the plane had been taken over for a suicide mission, Thomas Burnett had led the charge on the cockpit on flight 93. He and his fellow passengers managed to divert the plane from its target – the White House. The cockpit flight recorder captured his now-famous last words before they stormed the hijackers: “We’re going in!” Shortly after, the plane crashed, killing all 44 people on board. Burnett was 38 years old.

“It was such a moving meeting,” recalled Jodi Westbrook Flowers, a lawyer at Motley Rice. “It was clear that Thomas Burnett Jr was a really cool guy. We were very moved and we decided we would investigate.” The co-founders of Motley Rice, Ron Motley and Joe Rice, had made their names by taking on the asbestos industry in the 1970s and pursuing big tobacco in the 90s, winning multi-billion dollar settlements for the thousands whose health had been destroyed by their products. The firm saw in the plight of the 9/11 families an opportunity to continue holding powerful institutions to account for bringing about the deaths of thousands of innocent people.

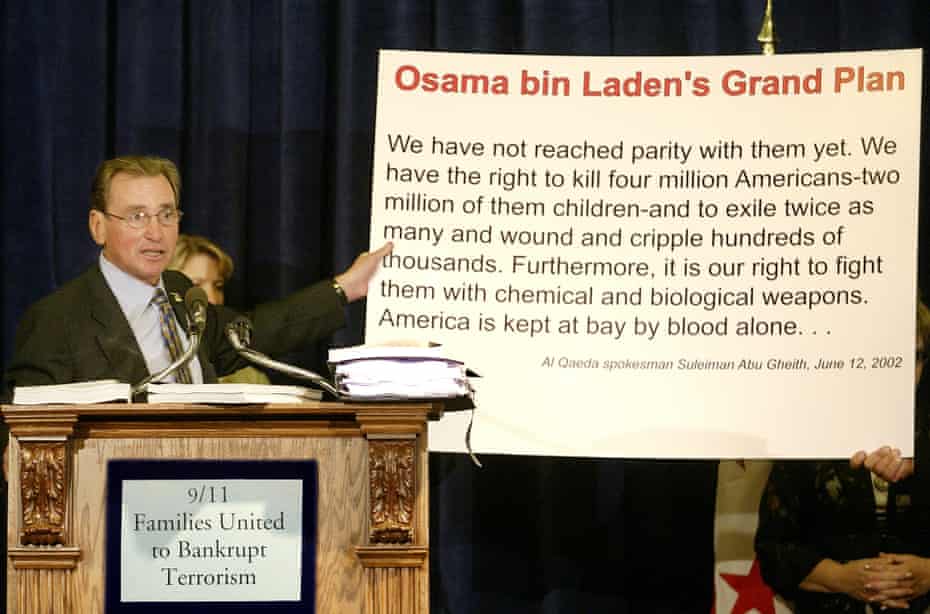

In the summer of 2002, Motley Rice filed legal action on behalf of the Burnett family and 500 people whose relatives were killed on 9/11. The suit named, among others, seven international banks, eight Islamic foundations, charities and their subsidiaries, alleged individual terrorist financiers, and the government of Sudan. The plaintiffs initially described themselves collectively as the 9/11 Families United to Bankrupt Terrorism; they later became the 9/11 Families and Survivors United for Justice Against Terrorism. The compensation claim filed was for $1tn. It was the largest terrorism-related civil action in history.

One of the plaintiffs, Terry Strada, lost her husband Tom on 9/11. Ever since, she has been seeking, more than anything, “acknowledgment” for what happened. “My husband was murdered. My kids were left without their dad. It’s been a hard life since then, raising them without him,” she told me. To Strada and the rest of the families, the organisations, governments and individuals that supported the 9/11 hijackers were “getting away with murder”.

On the list of defendants in the lawsuit, Sudan was the odd one out. No participant in the attacks was Sudanese, and while the majority of those listed were either Saudi institutions or individuals, Sudan was the only sovereign country accused of financing 9/11. Sudan was held accountable because its government had extended hospitality to Osama bin Laden between 1991 and 1996. The 9/11 plaintiffs argued that without the support Bin Laden received in Sudan, he would not have been able to muster the resources or the logistics to attack the US.

Almost two decades after it was first launched, the Families United case has still not gone to trial. During that period, however, Sudan itself has undergone profound changes. In 2002, at the time the legal action was filed, Sudan was impoverished. Its economy had been weakened by the corruption and warmongering of successive governments and further strained by years of sanctions imposed by the US. In 1993, the US had designated Sudan a state sponsor of terror (SST), adding it to a short list of rogue states: Iran, Iraq, Cuba, Libya, North Korea and Syria. The designation restricted economic aid, investment, trade and loans from international finance institutions such as the World Bank. Further economic sanctions, applied in punishment for human rights abuses and supporting terror, were also imposed by the US on the Sudanese government from 1997 onwards.

Sudan was largely cut off from formal commerce with the outside world. Everything from agricultural equipment to pharmaceutical goods and medical technology became hard to procure. In 2008, Sudan’s national carrier, Sudan Airways, was grounded for failing safety tests because it could not access spare parts. With very little to export – apart from gum arabic, a binding agent used in soft drinks, which was exempted from the embargo thanks to the successful lobbying of large soft drinks manufacturers – the foundations of Sudan’s already weak economy began to tremble. Unable to make money, the government began to print it, and Sudan’s economy entered a spiral of inflation. When the south seceded in 2011, Sudan lost most of its oil exports. “That’s when things started to come off the rails, and we are still living with the inflation effects of that today,” says Sudanese economist Yousif El Mahdi.

Some economic sanctions were lifted by the US in October 2017, but Sudan’s listing as a state sponsor of terror, and the sanctions related to that status, remained. Since seizing power in 1989 in a military coup, the government led by Omar al-Bashir had pursued an extremist version of Islam that had made Sudan a friendly place for terrorist organisations and figures such as Bin Laden. As long as Bashir remained in power, there was no way the US was going to remove the country’s listing as a state sponsor of terror. And as long as Sudan was listed as a state sponsor of terror, there was no chance it could make a real economic recovery.

Then, in 2019, in a popular revolution that took both his government, and the world, by surprise, Omar al-Bashir was deposed. A transitional government entered into negotiations with Washington, and in December 2020 it was announced that Sudan would finally be removed from the terror list. The country would at last be eligible for debt relief and international aid. It seemed like the start of a new future for Sudan. “It was like we were saying, we did it! Come and open the doors for us. Bashir is gone,” recalls Mohamed Hasan, one of the people who had taken part in anti-government protests in Sudan’s capital, Khartoum.

But there was a catch. During Sudan’s time on the terror list, it had been stripped of sovereign immunity in the US, meaning that the country lost its protection against being sued in US courts for terror attacks against US citizens. When Sudan was removed from the terror list, its immunity was restored, with one exception – the Families United suit. Sources familiar with talks between the the US government and the 9/11 families told ABC News last year lawyers were seeking $4bn as compensation from Sudan.

In other words, after the economic ravages of nearly three decades of sanctions, Sudan still faces a legal claim for damages of that could amount to billions of dollars. The fact that Sudan was under a new government was immaterial. Speaking for the 9/11 families, Terry Strada told me: “Removal of the regime is only half of the equation. The state is still accountable for the atrocities conducted under the previous regime.”

The Sudanese people’s hopes of economic relief and international support after the toppling of Bashir met a stumbling block in the shape of the 9/11 victims’ families’ long-fought quest for compensation for the loss of their loved ones. For those in Sudan who had expected Bashir’s removal to be the start of better relations with the rest of the world, the 9/11 case, according to Sudanese political analyst Magdi El Gizouli, “was nothing short of a betrayal”.

Sudan’s past is stained by links with terror groups. “There is no question that Sudan deserved to be put on the [state sponsor of terror] list in 1993,” says Cameron Hudson, a former CIA intelligence analyst and former chief of staff to the US special envoy to Sudan. Bin Laden had arrived in the country two years earlier, bringing with him his four wives and 14 children. At that time, Hudson told me, Sudan was advertising itself as a place of refuge for various terrorist organisations around the region and agitating for “revolution and terrorist acts across the Middle East”.

What is less clear, even 20 years after the event, is to what extent Sudan’s terror links in the early and mid-90s amount to direct responsibility for the 9/11 attacks. Peter Bergen, one of the few journalists ever to meet Bin Laden, believes that there were two sides to Bin Laden’s story in Sudan. There was his public posture as a businessman – and “there was some truth to that,” Bergen said. Bin Laden did indeed own and start several projects in Sudan, among them a tannery, a bakery, a million-acre farm and road construction projects. Then, there was the “more complicated part of the story”.

During Bin Laden’s time in Sudan, al-Qaida “really began to focus its energies on the United States”, Bergen said. Bin Laden began holding lectures in his home in Khartoum on Thursday evenings, where he would “increasingly talk of cutting off the head of the snake”. The snake in Bin Laden’s metaphor, the source of humiliation for all Muslims, was the US. For its part, the US was slow to respond to the threat posed by Bin Laden. “There was an awareness that he was tagged a dangerous figure, but we didn’t have a handle on him as I recall,” Donald Petterson, the American ambassador to Sudan throughout most of Bin Laden’s time there, told the Guardian in 2001.

During the early 90s, according to former al-Qaida members, Bin Laden ran an operation out of Sudan that distributed weapons, provided training, coordinated surveillance on terrorism targets in east Africa, and funnelled cash to operatives outside Sudan. Drawn by Bin Laden’s activity, foreign radicals arrived in Khartoum, which became a magnet for different Islamist groups.

I grew up in a house not far from the one Bin Laden rented in a quiet residential area of Khartoum. One Friday in 1994, when I was 16, four members of an Egyptian terrorist group sprayed gunfire into the prayer hall of a mosque in the neighbourhood of Omdurman. My family was driving past after Friday prayers, and instead of the usual scenes of people milling around peacefully, we saw several men run out of the mosque, shouting for help, their white robes stained with blood. One man staggered into the road and stood, dazed, with wild hair and blood on his front as the cars swerved around him. After shooting 16 people dead, the gunmen climbed into their cars and made their way to Bin Laden’s house to assassinate him. They failed, but another three people were killed.

By 1996, any economic benefit Bin Laden’s businesses were bringing to Sudan was outweighed by the trouble he was attracting. In May of that year, Bin Laden was expelled from the country and his assets were seized. But Sudan had moved too late to wash its hands clean of him. During his time in the country, he had begun planning and funding a major attack against Americans.

On 7 August 1998, two years after Bin Laden was expelled from Sudan, two bombs went off simultaneously, one at the US embassy in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, and another at the US embassy in Tanzania’s biggest city, Dar es Salaam; 215 people, most of them local citizens, were killed. Al-Qaida, under the leadership of Bin Laden, now based in Afghanistan, claimed responsibility. In the investigation that followed, it was revealed that in the years before the attacks and before Bin Laden was expelled, Sudan had provided passports and refuge to some of the militants involved in the bombings.

As an FBI supervisory special agent from 1997 to 2005, Ali Soufan oversaw complex international investigations into the east Africa embassy bombings and the events surrounding 9/11. When I spoke to him, he was firm in his belief that there are no proven links between Sudan and 9/11, but conceded that the county’s early associations with Bin Laden and its support of the east Africa bombers cast a long shadow.

Soufan pointed out that there are two parties that offered shelter to al-Qaida: “One is a non-state, the Taliban, and one is Sudan. So definitely they will go after Sudan.” In Soufan’s view, Saudi Arabia has much closer links to 9/11 than Sudan. “Fifteen of the hijackers were from Saudi Arabia,” he said. There are “a lot of questions that need to be answered” by the kingdom.

Sudan’s close ties to the east Africa bombings continued to create legal trouble and generate bad headlines for the country. But worse headlines were to come.

In February 2003, in the region of Darfur in western Sudan, an ethnic and tribal conflict exploded. The Janjaweed militias, as they came to be known, in conjunction with government forces, embarked on what Human Rights Watch called a “systematic campaign of ‘ethnic cleansing’ against civilians”. The war attracted Hollywood celebrities who drew attention to the government’s human rights abuses and called for sanctions. In 2007, George W Bush tightened sanctions on Sudan, and a little over a year later, the International Criminal Court (ICC) indicted Omar al-Bashir for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes in Darfur.

“Sudan became the bogeyman for every single liberal cause in the United States,” the former CIA analyst Cameron Hudson told me. “Whether it was religious freedom, child soldiers, slavery, you name it, Sudan was the top of the list of worst offenders, and Bashir and his people were the embodiment of the worst vices and human rights abuses in the world.”

Having been stripped of its sovereign immunity as a result of being listed as an SST, Sudan also faced a series of lawsuits. In 2001, James Owens, a survivor of the Nairobi US embassy bombing, had filed a civil lawsuit in a Washington DC federal court against Iran and Sudan, arguing that both countries provided support to the bombers, prior to the attack. Other victims and their families had joined the legal action. Stuart H Newberger, a senior partner with the international law firm of Crowell & Moring, represented all the Americans killed in the Nairobi US embassy bombing. “The case was slow in developing,” he told me, “because it wasn’t clear how well the CIA and the FBI could connect the dots between Sudan and al-Qaida. It took a long time.” His clients included Sue Bartley, whose husband Julian and son Julian Jr died in the Nairobi attack. Julian Bartley was the counsel general at the US embassy, and one of the highest ranking African Americans in the US foreign service.

Sudan ignored the case. In March 2003, after the country failed to send any legal representatives in response to a summons to enter its defence, the Columbia district court decided in favour of the plaintiff. Sudan then engaged legal counsel and tried to get the case against it dismissed, prolonging proceedings for years.

After Motley Rice filed the lawsuit on behalf of the 9/11 families in October 2002, Sudan, once again, did not respond. The law firm did not push because, according to Flowers, there was no real way to collect the damages if they won, because Sudan was not engaging with the case and the US had no leverage on the country to compel it to do so. Instead, the 9/11 families focused on fighting for the right to sue Saudi Arabia.

The 9/11 lawyers “went through three or four federal judges, up and down the circuit court, and all the way to the supreme court”, Flowers told me. They also applied pressure on political representatives. That effort culminated in the Justice Against the Sponsors of Terrorism Act (Jasta), an act first introduced in Congress in 2009 that allows victims to hold any foreign government accountable in US civil courts for terrorist attacks on US soil. In September 2016, Barack Obama vetoed the Act, only to have his veto struck down. Don Migliori, a senior attorney at Motley Rice, tells a striking story of a 9/11 family meeting with Obama before he exercised his veto. “He was quite angry,” he said. When asked why he opposed the bill, Obama allegedly said: “There are plenty of other people you can sue.” But Jasta finally passed in September 2016 when the veto was overridden by congress a few days later, and the plaintiffs won their right to pursue Saudi Arabia for damages.

Saudi Arabia was certainly in a better position to pay compensation than Sudan. By this stage, Sudan had spent 23 years on the terror list, was in its third decade of sanctions, and on the edge of a security and economic crisis.

As the terrorism-related lawsuits were winding their way through the US courts, the Sudanese people continued to carry the heavy weight of sanctions. The sanctions were so layered and varied that they touched almost every aspect of daily life, heaping more hardship on to a populace struggling under a corrupt and ruthless government. Basic food items such as bread became prohibitively expensive, and the healthcare sector was hit hardest of all. By 2010, after the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Omar al-Bashir, unrest was beginning to grow, not just in Sudan’s marginalised regions, but in Bashir’s stronghold of Khartoum and its surrounding cities. Between 2011 and 2013, triggered by the events of the Arab Spring, but maintained by rage against inflation and declining living standards, protests flared up and were violently suppressed.

Protesters were regularly detained, beaten and shot. The worst treatment was saved for those from Sudan’s rebel areas, the west of the country and the Nuba mountains. Amjed Farid, an opposition activist at the time, can’t remember how many times he was arrested in the last decade by Bashir’s regime. “We were beaten and abused, but still not as badly as others that the racist security forces targeted,” he told me. It is hard to find a household across the country that does not know someone who at some point was held in Bashir’s “ghost houses”, where those who fell foul of the government were held, tortured or disappeared.

When some US economic sanctions were lifted in 2017, in recognition of the Bashir government’s de-escalation of domestic conflict and increased cooperation with the US in combatting terror groups in North Africa, Sudan was allowed to deal internationally in US currency, permitting it to import spare parts for aviation, agriculture and medical equipment. But by then an economic crisis so severe had taken hold that the government started imposing limits on how much money people could withdraw from their own bank accounts. At the start of 2018, mobs gathered outside banks, where clients remonstrated and often fought with employees to allow them to withdraw their salaries.

The US uses sanctions to “signal displeasure”, rather than as a “deterrent”, says Jason Blazakis, who between 2008 and 2018 headed the US state department’s office responsible for designating countries, organisations and individuals as terrorists. Sanctions are “a clumsy tool”, he said, that create an environment in which ordinary people suffer. In his view, the “state sponsor of terrorism” designation was a tool that often backfired and empowered those it was meant to weaken.

While forcing ordinary Sudanese people into extreme hardship, sanctions banning foreign aid did little to weaken Bashir’s position. Documents procured by Bloomberg in 2017 showed that government-affiliated bodies managed to find ways to circumvent the bans, procuring licences for importing medical technology under the guise of humanitarian exemptions, and then using them to equip expensive private hospitals. This not only severely diminished the public health care system, but also funnelled cash into the pockets of government officials.

A legacy of the sanctions is that people in Sudan’s medical community have become resigned to the fact that many patients die for trivial reasons. It is common for people to enter public hospitals for relatively mild ailments and then never come home. Maternity services have been particularly badly affected. Sudan’s infant mortality rate is among the worst in the world, with 40 deaths per 1,000 live births. Premature babies have little chance of survival.

Dr Eshraqa Seifaldeen is a young doctor who grew up under sanctions. She works in a hospital in Khartoum that has no oxygen, no saline drips, no ventilators and no heart-rate monitors. An obstetrician by training, Seifaldeen tries to plug the gaps across specialisms at the understaffed hospital. “The hospital has nothing,” she told me earlier this year. “The way the system works is that every time a patient arrives, we send their families to purchase basics and life-saving medicines. If they don’t have the money, we just ask them to check other hospitals in the area.”

Seifaldeen is haunted by the case of a woman who had spent 15 years trying for a baby, and finally became pregnant with twins. In 2019, when she went into labour prematurely at 34 weeks, she went to the hospital in which Seifaldeen worked. She was told that the newborn intensive care unit was no longer viable, and was sent elsewhere to look for any other facility that might have an incubator free. Still in labour, she was turned away at every other hospital, and finally returned and asked to be admitted. “If they live they live, if they die they die,” she told the doctor.

After a complicated labour, Seifaldeen delivered both babies, but only one survived. “I can’t get that case out of my head,” says Seifaldeen. “She had waited so long to have children, and even though she lost a baby that she didn’t need to lose – 34 weeks isn’t that early, it could have survived – she was still happy she didn’t lose them both.”

The revolution that finally toppled Bashir found its heart at a colossal sit-in at the country’s military headquarters in Khartoum, when tens of thousands refused to move until Bashir stepped down. The atmosphere on the streets of Khartoum the day Bashir was removed from office, 11 April 2019, was of a people waking up to something they had not felt in a long time – hope. The new transitional government, a mix of civilian figures and military and paramilitary forces, set about reintegrating Sudan into the international community. But as long as Sudan remained on the state sponsors of terrorism list, that would be impossible.

Negotiations with the US began in early 2020. The timing was good. Donald Trump, then gearing up for a re-election campaign, saw an opportunity. The Trump administration agreed to look kindly on Sudan’s request for removal from the terror list, but it wanted something in return – recognition of Israel, and payment of damages to victims of the 1998 east Africa terror attacks. A final judgment had been made in the case by the US supreme court in May 2020. The court ruled that Sudan’s role in the embassy bombings had been proven, and the country was ordered to pay “compensatory and punitive damages” of $10.2bn, roughly 30% of Sudan’s gross domestic product that year. The Trump administration also insisted that Sudan would still have to answer the charges of supporting terrorism the 9/11 families had filed almost 20 years before.

This last demand came as a surprise to Sudanese negotiators. In September 2020, Nureldin Satti, the country’s ambassador to the US, told reporters that Sudan had expected that removal from the terror list would mean that the 9/11 case could not proceed. Without full immunity from such lawsuits, Sudan’s economy “could not recover”, said Satti.

A political scuffle broke out in the halls of DC, with Sudan supporters in the state department and the Senate – the most high-profile of whom were secretary of state Mike Pompeo and Senator Christopher Coons – pressing for the case to be dropped. The 9/11 families and their advocates pushed hard to prevent their claims against Sudan from being extinguished. Two powerful east coast senators, Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer, and Bob Menendez, the most senior Democrat of the powerful Senate Foreign Relations Committee, lobbied on behalf of their New York and New Jersey constituents who made up the majority of the 9/11 families. They won.

In October 2020, Sudan negotiated a settlement for the victims in the east Africa bombings, and paid out $335m in compensation – a fraction of the $10.2bn the US courts had originally set. The country’s terror designation was removed, and the “courthouse door” was closed to future lawsuits. But the 9/11 claims for billions of dollars in compensation from Sudan had to be seen through.

In post-revolution Sudan, the 9/11 families’ lawyers were facing a new, more internationally cooperative government keen to show the world that it had moved on from Bashir’s brutal and pugnacious regime. Almost 20 years after announcing their legal action, in November 2020, the 9/11 families finally filed a demand for a jury trial in the southern district of New York district court. They demanded damages for “wrongful deaths, personal injuries, and property damage and economic loss caused by the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks upon the United States.”

For the fledgling government in Sudan fighting the case, the fruits of the removal from the terror list cannot come fast enough. There are several little fires burning at its feet, each with the potential to engulf it. Queues for petrol snake through entire neighbourhoods. Power cuts are a daily occurrence. In the first quarter of 2021, inflation reached a record 341%, behind only Zimbabwe and Venezuela. Protests are beginning to flare up again. The dividends of the revolution are becoming harder and harder to believe in.

More troubling is the fact that the new government is not quite the clean break from the past that it claims to be. Its powerful military and paramilitary wing is populated by those who served in Bashir’s government, and who are themselves accused of committing or facilitating war crimes in Darfur. Omar al-Bashir, wanted for crimes against humanity since 2009, remains in Sudan in a reform facility, effectively under house arrest, convicted only of corruption.

The economic crisis threatens to trigger another military coup and let Sudan slide back into dictatorship or worse – anarchy and failed statehood. A government advisor who wishes to remain anonymous recently told me that the country was heading for “disaster”.

The 9/11 families are now pursuing both Sudan and Saudi Arabia simultaneously. The case is in the depositions stage, during which a judge will rule on whether there is enough evidence to proceed to a trial during which damages can be determined. Attorney Jodi Westbrook Flowers says that many of those family members – “pioneers”, she called them – who filed the original case against Sudan are still committed to pressing ahead, despite the long and fruitless quest so far. The firm receives frequent messages from the families, she said, expressing gratitude that “at least somebody didn’t forget us”. As the 20th anniversary of 9/11 approaches, the families’ stories, and their lawsuit, will receive renewed attention. The Sudanese government, in a late rearguard action, has filed a motion to dismiss the case owing to lack of evidence.

Whatever the outcome, for both the 9/11 families seeking redress for their loss, and the Sudanese people trying to crawl out from under the weight of decades of sanctions, justice for one will come at the expense of the other. “We paid the price twice” for Bashir’s dictatorship, says Amjed Farid, the opposition activist. “We got rid of the tyrant who was supporting terror, through a popular revolution that we paid for with our blood. And now we are paying the price for this tyrant, even though we were his first victims.”

by Nesrine Malik

Source: Guardian