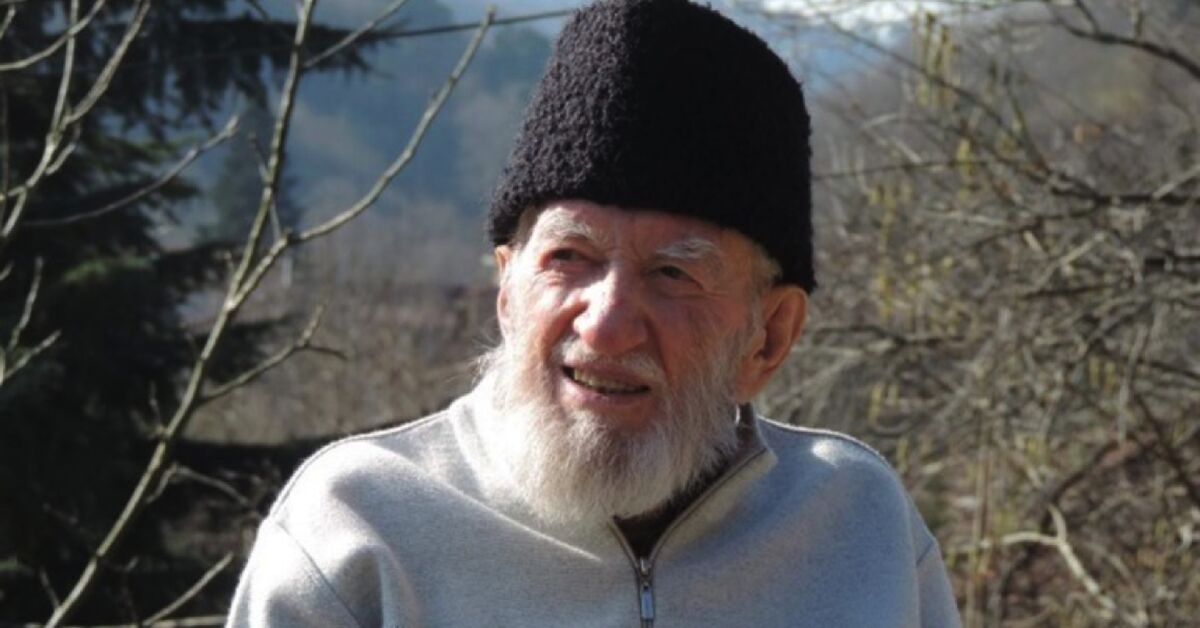

Prominent Islamic scholar Jawdat Said, whose uncompromised rejection of violence and devoted advocacy for nonviolent protests against the Syrian government earned him the title of Syria’s “Arab Gandhi,” died at the age of 91 in Istanbul where he had taken refuge to escape the war.

Said was one of the signatories of the so-called Damascus Declaration, a joint statement embraced by large segments of Syrian society including Kurds, members of Syrian Muslim Brotherhood and other Syrian opposition leaders who called for a peaceful transition and reform process in Syria.

The preacher moved to Turkey in 2012 after his brother was killed in armed clashes between Syrian government forces and the radical Islamist group Jabhat al-Nusra in the southern Syrian province of Quneitra.

Declining offers of help from Turkish government bodies and officials, he and his wife, who died last year, survived mainly with the support of family and Circassian organizations.

Although known as the Arab Gandhi, Said was an ethnic Circassian who was born in a Circassian village in Quneitra on the Syrian side of the Golan Heights.

Hailing from a prominent Circassian tribe, Tsey, Said’s ancestors settled first in the Balkans and then in Golan after their expulsion from their homeland by Russians in the 19th century.

Inspired by late Algerian intellectual Malek Bennabi’s studies on Muslim communities, Said’s view of Islam was a blend of ideals of humanity including peace, pacifism, human rights, democratic values and Circassian traditions.

He praised Turkey’s democracy experience as a template for predominantly Muslim countries and its now-stalled bid to join the European Union, calling reinterpretation of Islam.

Yet his staunch opposition to all forms of violence that he had advocated for over the past 60 years was never really understood either by his fellow Islamists or his own Circassian people. He decisively lamented the absence of sufficient effort in the Muslim world to develop ideas prioritizing nonviolence, civil disobedience and democracy in his numerous speeches and interviews.

He was active during peaceful protests in Syria in 2011 before the maelstrom morphed into a bloody civil war. Back then, in a gathering in the southern Syrian region of Hauran, he warned Syrian activists not to resort to arms under any circumstances. Maintaining his position during the civil war, he fiercely criticized those who took up arms.

Yet Said’s persistent defiance of all forms of violence hardly matched with expectations of Islamic groups from a preacher who was imprisoned by Syrian authorities several times for his dissenting views. Islamists who believe armed struggle is the only option for self-defense were quick to shut their ears to him. In fact, his views have been well known since the 1950s.

After he settled in Turkey, Turkey’s Islamist groups and pro-government media outlets attempted to portray him as a scholar “who escaped Syrian President Bassar al-Assad’s brutality” in a bid to canvass support for the Turkish government’s Syria policies.

Said, whose several books have been translated into Turkish, was first received with great adulation in Turkey. He addressed more than 100 conferences in various cities around the country.

This adulation gradually turned to avoidance, as his decisive nonviolence position failed to match the expectation of those who hosted him, a source close to Said told Al-Monitor. The interests in the preacher gradually dimmed, and he was pushed into isolation, the source recalled. His advocacy for nonviolence even earned him tell-offs from Turkey’s pro-government circles. Hayrettin Karaman, a Turkish Islamic scholar and columnist close to the government, went as far as to accuse him of “playing into the hands of the tyrant,” without mentioning Said’s name.

In press interviews, he was often challenged with questions on whether he was “for the Syrian regime or the opposition.” His answer remained the same: As a dissident who was imprisoned several times by the Assad administration, he said that he was both opposed to the Assad administration’s tactics to instrumentalize violence and armed struggle against it, stressing that peace and democracy can hardly be achieved with arms.

“The rebels are resorting to arms to fight [the Assad administration]. Arms are nasty. They shouldn’t have taken up arms in the first place. They should have thrown roses at those who shot them. This is what I would have done if I was in their shoes even if my wife and children were killed by them,” he said in one of his interviews. “You Turks know nothing but weapons,” he added after the interviewer confronted him by arguing that the Syrian people had no other option than to take up arms.

Former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, leader of the Future Party, was one of the very few political leaders to attend Said’s funeral on Jan. 31 in the central Istanbul district of Uskudar, along with the Istanbul governor and the mayor of Uskudar. The Justice and Development Party (AKP) and Islamic intellectual circles who initially welcomed him with open arms were tellingly absent from Said’s low-key funeral.

The Turkish government’s reaction to his death, meanwhile, has been confined to social media messages with Turkish Vice President Fuat Oktay and presidential spokesperson Ibrahim Kalin offering their condolences via Twitter.

During his funeral arrangements, some bureaucrats from Ankara floated the idea of burying him in a tomb at the compound of Istanbul’s Fatih Mosque where Said’s fellow alumni of al-Azhar rest, but the appeals conveyed to the Turkish presidency for the issuance of the necessary Cabinet permit have gone unanswered, according to his close acquaintances who spoke to Al-Monitor under condition of anonymity.

The incident is widely seen as a reflection of the disappointment Said unleashed among the AKP ranks by refusing the heading of the government’s line on Syria. Even his close friends, including schoolmates from al-Azhar, refrained from visiting him while he was alive. The only AKP official who visited him at his home was Mehmet Gormez, former head of Turkey’s official religious body Diyanet.

This was the price Said paid for his unyielding stance. In his close circle, he was known as a man of dignity who led an utterly plain and modest life. Avoiding accepting any valuable gifts from Turkish officials or other influential individuals, he declined any offers to help him to lead a more comfortable life. The life he built for himself in Istanbul wasn’t different from his modest life in Quneitra where he had lived with two cows, a few beehives and a rusty bike.

As the only globally renowned Circassian religious scholar, Said held a special place among the Circassian community. Yet much to the community’s whining, he preferred to remain reserved when asked for his opinion on Circassian problems such as ethnic and cultural assimilation; instead, he refrained from preaching specifically for the Circassian community.

Meanwhile, he always upheld Circassian traditions and culture throughout his life. For example, he used to host his female and male guests together, contrary to some Islamic practices where men and women sit in separate rooms. Listening to fluent speeches he would give in the Circassian language was one of the most pleasing aspects for audiences attending his conferences organized by Turkey’s Circassian community.

Source:Al-Monitor

***Show us some LOVE by sharing it!***