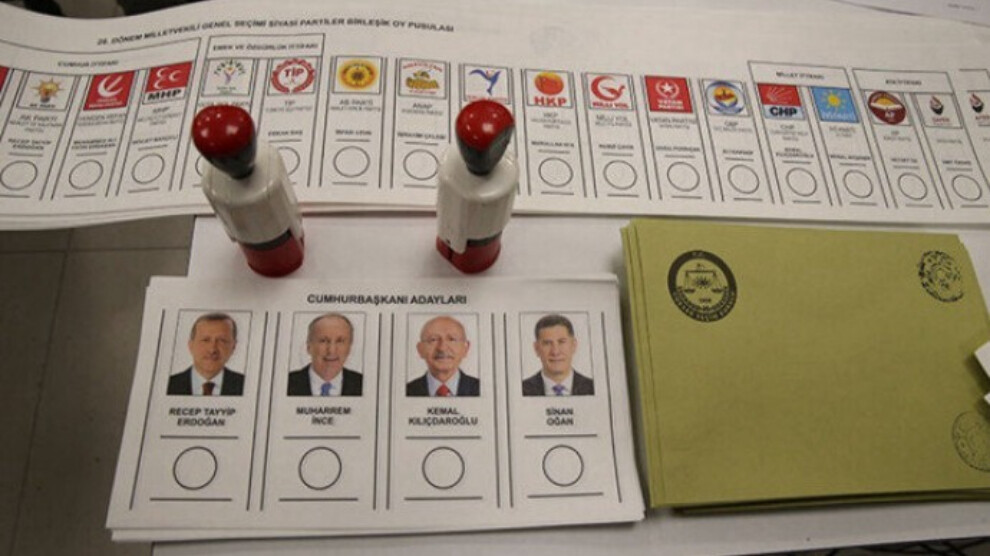

The Turkish diaspora around the world has mobilised for the presidential and legislative elections in May 2023. Although the diaspora is not a homogenous group, and its choices are influenced by social, ethnic and even religious divisions, 60 % of them voted for Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Turkey’s global diaspora is made up equally of migrants from their mother country and people born in the countries where they now live. During the May 2023 elections, the spread of this worldwide diaspora became clear, as ballot boxes were installed in 73 countries, 167 different cities and 53 customs posts: it was no longer a matter of just a few Western European countries that had welcomed labour and family immigration since the 1960s.

For decades, the many migrants from Turkey to five Western European countries – Germany, France, Austria, the Netherlands and Belgium – were viewed critically by the “homeland”. The gurbetçi (expatriate) vote provoked a recurring debate in Turkey. Not only were these emigrants seen as temporary, but the prevailing national-secularist bureaucracy often judged them to be too Islamist, too Kurdish and, in some cases, too leftist.

From 1987 onwards, expatriates in these Western European countries began to be allowed to vote in Turkish national elections, but only at customs posts, which for logistical reasons considerably limited their turnout. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, political and identity-based organizations, particularly those representing political Islam, chartered buses to transport voters to the borders.

It was only in 2012 that a decree permitting the establishment of ballot boxes in diplomatic representations was passed, allowing the diaspora the status of an actor in Turkish domestic politics. From the 2014 elections, Turkish nationals living abroad, whether immigrants or born in the countries of their residence (regardless of whether they had ever set foot in Turkey) were able to vote at consulates in their countries of residence. However, an appointment system limited their chance of voting and also violated the principle of voting secrecy (consulates knew who was going to vote since appointments were required). Since 2014, things have improved and it is now possible to vote in any Turkish diplomatic outpost over a four- to six-day period.

However, two problems remain. Firstly, the principle of open counting is systematically violated, since ballot papers are not counted under the supervision of the voters themselves but sent to Ankara to be counted with domestic ballots. As a result, voters in the diaspora are unable to keep track of their ballots.

More importantly, there are no extra-territorial constituencies. Turkish nationals abroad have no opportunity to elect representatives. They have the right to vote, but not to be elected. Thus voters cast their votes primarily on the basis of identity concerns, and are more subject to the state’s nationalist and religious propaganda. What’s more, under this system, the diaspora vote has minimal impact in parliamentary elections, in contrast to its real impact in presidential elections (or referendums). This situation gives rise to debate in Turkey itself, where people often accuse voters living in democratic Western countries of favouring the election of an authoritarian president – and not suffering the consequences or being held accountable through elected representatives. This is precisely what happened in the parliamentary and presidential elections of 14 and 28 May 2023.

700,000 PEOPLE IN FRANCE HAVE LINKS WITH TURKEY

People originating from Turkey in France form one of the largest diaspora communities, second only to Germany in terms of numbers. Around 700,000 people in France have links with Turkey; half of them are Turkish citizens and the other half French citizens or dual nationals. At the May elections, there were just under 400,000 voters in France. There are also – although this is an estimate – 100,000 people of Turkish origin who do not hold Turkish nationality, first as refugees and then as French nationals; or children born on French soil whose parents have not declared them to the Turkish authorities. The latter, of course, are not eligible to vote.

What’s more, since 2016, an influx of immigrants has settled in France, belonging either to the Gülen movement (named after the U.S.-based preacher Fethullah Gülen, first viewed as a paragon by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, then his fierce opponent) or to the intellectual class – academics, artists, journalists – driven out of the country in a more or less coercive manner. Whether Gülenists or leftists, they also don’t vote, because they’re not properly registered on the lists of Turkish residents in France.

In 2023, for the legislative (14 May) and presidential (14 and 28 May) elections, 400,000 voters (dual nationals or Turkish nationals legally living in France) were called to vote. For the second round, in which the incumbent, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, faced his rival, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, voters had the opportunity to go to the polls between 20 and 24 May in the following French cities: Bordeaux, Clermont-Ferrand, Lyon, Marseille, Mulhouse, Nantes, Orléans, Paris and Strasbourg.

Turnout for the second round of the presidential election was 52 %, and while this may seem acceptable for national elections in France, it remains relatively low compared to the 88 % turnout in Turkey. As a result, the 207,000 voters in France were only a tiny fraction of the 54,000,000 eligible to vote.

SIGNIFICANT REGIONAL DISPARITIES

Turnout was slightly up compared to the first round, whereas observers were expecting a drop, due to overconfidence among Erdoğan’s supporters and/or a sense of demoralization among Kılıçdaroğlu’s supporters. However, both sides mobilized to such an extent that between the two rounds, votes in favour of Erdoğan increased by 10,000, while those in favour of Kılıçdaroğlu increased by 2,500. This difference can be explained by a hardening of the opposition’s discourse between the two rounds, with the aim of rallying the far-right candidate’s votes – but which also had the consequence of chilling part of the Kurdish electorate in France.

Overall, Erdoğan won the election with 67 % of the Turkish vote in France, increasing his score by three points compared to the 2018 elections. Significant regional disparities are also evident on an international scale. It’s true that for the diaspora as a whole (3,400,000 voters), Erdoğan won the election with 60 % of the votes cast (the turnout rate for the diaspora as a whole was 56 %). However, in countries with a classic migration history, mainly focused on work and family reunification, such as Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Austria, Erdoğan won a landslide victory. In other European countries such as Norway, Sweden and Switzerland, the score is much more balanced. On the other hand, in the US, Canada, Australia and the UK, home to communities belonging to the middle and upper classes, Kılıçdaroğlu achieved overwhelming scores.

ROLE OF THE CLASS FACTOR

This disparity linked to social class differences can also be seen in France. In some cities with very conservative communities, particularly from Central Anatolia and along the Black Sea coast, the results were overwhelmingly in favour of Erdoğan. Clermont-Ferrand holds the world record for the pro-Erdoğan vote with 92 %, followed by Lyon with 88 % and Orléans with 87 %. The latter two cities are also known for the presence of the “Grey Wolves”, Turkey’s extreme nationalist right. The city of Bayburt, in northeastern Anatolia and known as a bastion of the ideology of Turkish-Islamic synthesis, ranks fourth with “only” 82 % of votes in favour of Erdoğan.

Strasbourg, Mulhouse, Bordeaux and Nantes (with scores ranging from 60 % to 70 % in favour of Erdoğan) are close to the French average. Bas-Rhin and Haut-Rhin are home to a sizeable community, with 70,000 and 40,000 Turkish nationals respectively, mainly from cities such as Konya, Kayseri, Malatya and Erzincan, although there is also a certain degree of diversity. Strasbourg has the distinction of being both the French centre of Millî Görüş, a movement of Turkish political Islam that was part of the opposition coalition, the DITIB (Presidency of Religious Affairs or Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı), the official Islam that campaigned for Erdoğan throughout the month of Ramadan, as well as Alevis of France, who leaned almost exclusively towards Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu.

Strasbourg also boasts a large Kurdish community, as well as a student population on the one hand, and Turkish civil servants from European institutions on the other. Consequently, the 70% in favour of Erdogan and the 30 % in favour of Kılıçdaroğlu in this city mask far more complex affiliations. A proportion of Kurds do not (or no longer) hold Turkish nationality, which prevented them from voting. As for students and European institution workers, who are often secular and individualized and therefore potentially in favour of Kılıçdaroğlu, many did not vote. Thus, in this city the political and identity distribution of abstentionists was not balanced.

In Paris, also home to just over 75,000 Turkish nationals, the score was much more in line with national results, with 52 % in favour of Erdoğan and 48 % in favour of Kılıçdaroğlu. This can be explained by the fact that in the Paris region, the identity-based cleavages between Turks and Kurds, Sunnis and Alevis, and religious and secular, were reproduced almost identically. Finally, in Marseille, home to the majority of Kurds and secularists among the 25,000 Turkish nationals, 56 % voted for Kılıçdaroğlu and 44 % for Erdoğan.

Though these scores deserve further study, we can see the reproduction of identity cleavages, both at macro and micro levels that exist in Turkey, even among generations born in France. One of the possible causes of this persistence could be the relative stagnation of these generations’ upward social mobility, as clearly demonstrated by the survey by the Institut national d’études démographiques (Ined) and the Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (Insee) entitled Trajectoires et origines (2017). The paternalistic control of Turkey, through an extremely effective ideological apparatus that works to maintain the regime in place in Turkey, also prevents detachment from the “homeland”. In addition, Turkey’s rich and diverse cultural offering, including TV series, music and popular shows, projects an enviable and envied image of life there, at least perceived as better than in France. All these reasons, combined with Erdoğan’s charisma as a leader who defies the West, against which these communities feel the need for revenge, partly explain their support for Erdoğan.

By: SAMIM AKGÖNÜL, director of the Turkish Studies Department at the University of Strasbourg.

Source: OriennXXI