Undermining the foundational pillars of the post–Cold War security order, Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine is a watershed event for Europe and the wider world, Turkey included. While Ankara is trying to protect its economy and security interests, anti-Western narratives dominate the public debate. The war has indeed accentuated anti-Westernism as one of the main fault lines of political competition. Given the geopolitical imperatives that February 24 brought to the fore, it is highly likely that, in the short-term, Turkey’s NATO membership and its Association Agreement with the EU will – geopolitically and economically – continue to anchor it to the West. Whether or not a full strategic alignment with the EU will accompany such an anchoring is far from certain, however, mainly due to Turkey’s domestic political dynamics, but also due to the unclarity about how far the EU is willing to move beyond a transactional approach.

In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ankara has so far hedged its bets and protected its economy and security interests. Turkey has over the years become Ukraine’s largest foreign investor. In early February, the two countries signed a free trade agreement. Ukraine is also an important market for Turkish drones, and Ankara is eyeing Kyiv for cooperation in defense technology. Meanwhile, Russia is one of Turkey’s largest trading partners for imports and one of its main gas suppliers. Tourism from Ukraine and Russia is a vital revenue source for a rapidly deteriorating Turkish economy. Wheat trade with both countries amounts to around 80 percent of Turkey’s imports.

Ankara is carefully trying to not antagonize Russia while continuing to militarily support Ukraine. Besides the economic burden that an open confrontation with the Kremlin might inflict on Turkey, it could also lead to military retaliation in Syria and to a subsequent migration wave from Idlib to Turkey, which hosts the largest refugee population worldwide. At the same time, the increased Russian presence in Ukraine, particularly along the coastline in the south, further raises Turkey’s strategic vulnerability in the Black Sea, accentuating its Cold War threat perceptions.

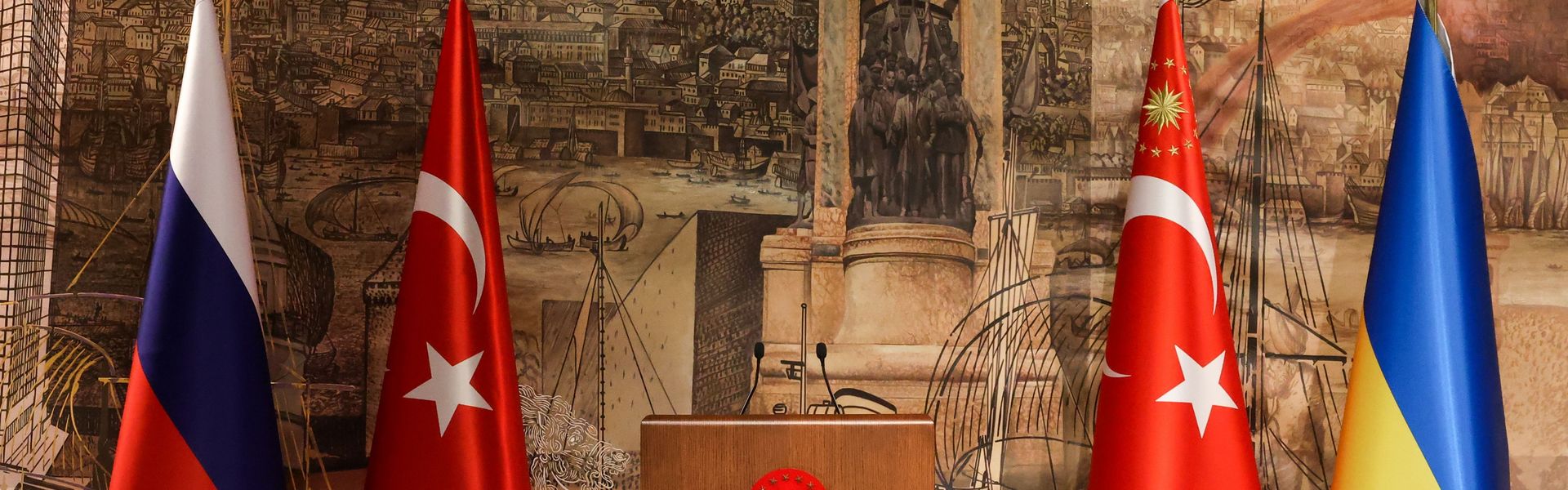

Ankara justifies its non-participation in the EU’s sanctions regime with these economic and security considerations. Turkish airspace also remains open to Russia. Still, Turkey is acting in close coordination with NATO and has repeated its firm commitment to Ukraine’s territorial integrity and sovereignty numerous times. Recognizing the violent conflict between the two countries as “war,” in accordance with the Montreux Convention, Ankara closed the Straits to warships from any country, whether or not they border the Black Sea. Meanwhile, it is also acting as a mediator between Ukraine and Russia.

The War Overlaps with Ankara’s Rapprochement Efforts

There is a broader context to this seeming balancing act. Putin’s war in Ukraine is hitting President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his foreign and security policy entourage during a charm offensive to break the country’s isolation and ease accumulated friction in relations with the US, the EU, and NATO. Since the failed 2016 coup, Turkish foreign policy-making has been driven primarily by the readiness to “pull [the country] up by its bootstraps,” referring to the determination to pursue Turkey’s own interests – if necessary with hard power.

Two premises have been driving Turkey’s foreign policy since then. First, because of a perceived lack of solidarity during the attempted 2016 coup and the US partnership with the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the People’s Protection Units (YPG) in northern Syria against ISIS, Ankara believes it can no longer fully trust its Western partners. Second, it regards the West as being in terminal decline owing to the retreat of liberalism and the power vacuum created by the US withdrawal from its multilateral commitments under the Trump Presidency.

Yet, Joe Biden’s election in November 2020 was an important inflection point for Turkish foreign policy, which had already reached its limits, particularly against the backdrop of a rapidly deteriorating economy. Since then, Ankara has stepped up rapprochement efforts with Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and most recently with Israel and Armenia. Senior Turkish officials signaled to the White House Ankara’s eagerness to resolve conflictual issues. Ankara also tried to regain leverage in relations with NATO by volunteering to safeguard the Kabul airport after the hasty American withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Taliban’s subsequent seizure of power. Still, all of this did not yield a significant improvement in relations with Turkey’s Western allies. Attitudes on both sides of the Atlantic are now marked by a wait-and-see approach until Turkey’s presidential and parliamentary elections in 2023.

For Ankara, the war in Ukraine erupted during this slow-running moment. Importantly, Turkey’s geographical position, its relevance with regard to the implantation of the Montreux Convention, its NATO membership, and last, but not least, Ankara’s close relations with Ukraine and Russia seem to have facilitated the Turkish leadership’s ability so far to break the country’s isolation. Its efforts to act as a mediator are welcomed in Western capitals. During his first official visit to Turkey on March 14, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz claimed Germany and Turkey were “completely united” on the issue of Russia’s war in Ukraine. In his phone call with Erdoğan on March 10, Biden was also reported to have expressed “appreciation” for Turkey’s “efforts to support a diplomatic resolution to the conflict,” and for its “recent engagements with regional leaders that help promote peace and stability.” After almost five years of stalemate in relations, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte also met Erdoğan in Ankara ahead of the NATO meeting on March 24, emphasizing Turkey’s “political and military importance for NATO” and that Ankara is a “important partner for the EU.”

To better understand Turkey’s position vis-à-vis the Ukrainian war, it is necessary to have a closer look at how different actors both within Turkey’s ruling alliance between the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the ultranationalist Nationalist Action Party (MHP) and those within the opposition relate to and perceive it.

An Overconfident Ankara

For Erdoğan, Western leaders’ renewed attention to Turkey, despite their earlier reluctance to reset relations, is evidence of the country’s increased geopolitical significance. Based on this assumption, the Turkish leadership sees the current moment as an opportunity to pressure its Western allies on several conflictual issues, particularly in the areas of defense and security.

For instance, Erdoğan told Biden that it was time to lift all “unjust” sanctions on Turkey’s defense industry, referring to the CAATSA measures for Ankara’s purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defense systems. Similarly, commenting on the S‑400s during the press conference with Scholz, Erdoğan noted that Turkey would act according to the “opportunities and limitations that the upcoming developments would bring.” Turkish Minister of Defense Hulusi Akar also asserted in a conversation with the press after the emergency meeting of the NATO Ministers of Defense in mid-March that Turkey has been, since it became a NATO member, fully committed to NATO and expects that its NATO allies are equally committed to Turkey and its efforts to counter “terrorist organizations such as PKK/YPG, ISIS and FETO.”

If the perception of Turkey’s increased geopolitical importance is one reason for Ankara’s overtures to NATO (and the US), the unity of the EU and the US, particularly at the onset of the invasion, in confronting Russia economically is another. This unity appears to have cast doubt on Ankara’s fundamental assumption about a post-West world order. Since early March, pro-Western tones in Ankara’s narrative have become noticeable. For instance, in a press conference with the President of Kosovo, Vjosa Osmani, Erdoğan noted that as a long-standing candidate country to the EU, Turkey “would support any enlargement of NATO and the EU,” endorsing the Ukrainian bid for EU membership. In fact, Ankara is treating the current moment as an opportunity to also insist on receiving special consideration in Turkey’s EU accession process. It is no coincidence that, during the same press conference, Erdoğan asked the EU to show “the same sensitivity” for Turkey’s membership status.

While Erdoğan and his foreign and security policy circle see the war as an opportunity to repair defense and security cooperation with the West, and to move ahead with the EU membership process, pro-government media puts the emphasis somewhere else. As the war is prolonged and its outcome being far from certain, commentaries since late March about a multipolar post–February 24 world, in which the West is only one center of power, have not been uncommon. The Turkish leadership’s role as a mediator in the war and its warm reception in Western capitals are perceived as evidence of Turkey’s growing influence, thanks to its autonomous foreign policy.

In fact, since the war started, pro-government pundits have consistently propagated Turkey’s increasing importance by emphasizing three points: i) Ankara’s success in diplomacy, which is being measured by the widespread attendance at the Antalya Diplomacy Forum of Western and non-Western leaders in March; the recent bilateral visits by Israel, Greece, the US, and Germany; and Turkey’s role as a mediator between Ukraine and Russia, ii) Erdoğan’s criticism of the West for failing to act unitedly against Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, and relatedly, iii) the structural weaknesses of the post–World War II institutions as evidence of the merit of Erdoğan’s calls for reforming the UN system.

A Weaker Ruling Alliance

Turkey’s rise against the West is a common theme among different actors within the ruling alliance as well. In his weekly address to the party on March 3, the MHP’s leader, Devlet Bahçeli, for instance, held both “Russian aggression” and “provocations by NATO and Western countries” responsible for the “Ukrainian crisis.” Emphasizing in the same speech the importance of respecting Ukraine’s territorial integrity and national sovereignty, Bahçeli called upon NATO to “reconsider its expansion to the East” and to “stop consolidating power and uniting its members by manufacturing fears.” He further asserted that Turkey “should not sacrifice its relations with friendly countries and neighbors” and that it will neither “be a frontline state” nor “get into war on behalf of the West.”

With these remarks, Bahçeli hit two birds with one stone. For one, he distanced himself from NATO and the US against the backdrop of the deep-running geopolitical aspirations of the Turkish ultranationalists over the Caucasus and Central Asia. He also tacitly criticized Erdoğan for his encouragement of NATO expansion.

Since the municipal elections in 2019, cracks within the ruling alliance are salient. Despite the MHP’s low share of the vote, Bahçeli seems to be pulling the strings in shaping the limits of policy, especially concerning law and order issues. This, to a large extent, is an outcome of his success in bypassing Erdoğan in the decision to re-run Istanbul elections by forming an alliance with the hawkish elements within the AKP, particularly the so-called Pelikan, a network of militant journalists and opinion leaders associated with Berat Albayrak – Erdoğan’s son-in-law and the former Minister of Finance and Treasury – and the Minister of the Interior, Süleyman Soylu.

Even though Albayrak left office in early November 2020, the media network associated with him continues to shape perceptions. For Hıncal Uluç – a columnist at the daily Sabah, owned by the family of Berat Albayrak – the recent visits by the world leaders in Ankara demonstrate Turkey’s power against “the West that wants to treat Turkey like a colony.” The war in Ukraine has shown, Uluç argued, that “Turkey is – with the support from the East – able to get on stage on an equal basis alongside with the West” thanks to “Albayrak’s vision to turn his face to the East” and to “Erdoğan’s support and leadership.”

In an interview on March 14, Minister of the Interior Soylu similarly noted that the war shows that Turkey has become a center of attraction for “low and middle [income] countries,” while the “UN, NATO, and global institutions are going bankrupt” and “the EU is no longer meaningful as a community.” For Soylu, the Kremlin reacted against US efforts to contain Russia “at a time when the vulnerability of the US and the EU reached a peak under the pandemic.” The war, in Soylu’s world, symbolizes the end of globalization as nation-states rise to power. And in this new setting, Soylu claimed, “those who unlawfully demand the release of Osman Kavala [the Turkish philanthropist who has been unlawfully kept in prison for over four years on unjustified coup-plotting charges] are the same with the murderers of children in Ukraine and Syria.”

Today, Soylu is also frail, especially following a series of corruption allegations raised by the mafia boss Sedat Peker, but he is not weak enough to be ousted from office – which is a common practice under the Turkish presidential system. Anti-Westernism is a rhetorical tool to safeguard his still privileged yet fragile status in an increasingly weaker alliance. Yet, for him and other anti-Western voices within the AKP/ MHP alliance, blunt opposition against the so-called West is also being driven by fantasies about a Turkic Muslim world, the dislike of Western culture, and an authoritarian impulse.

The Far-left’s Anti-Americanism

Anti-Western narratives that the war has accentuated echo within far-left circles as well. At the center of the denunciation of the West is anti-Americanism.

Following the acquittals of various political and security factions in the early 2010s in the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer trials, it is no coincidence that they did not shy away from endorsing and even shaping – implicitly and explicitly – some of the AKP’s foreign policy adventures, and that they are now watching the invasion closely. As important carriers of Eurasianism in today’s Turkey, these actors see the war in Ukraine first and foremost as a proxy war between the US (in cooperation with Europe and NATO), on the one hand, and Russia and China on the other. They also approach the war as the new militarized phase of a process through which the center of gravity is shifting to Asia.

A general bitterness about the US underlines this view. The perceived attempts by the US to push Turkey away from Russia by utilizing the war in Ukraine are seen as part of a longstanding trend to pull Turkey into the American sphere of influence following the fall of the Soviet Union (a view paradoxically shared by Islamists as well). The post–Cold War history of US-Turkey relations is accordingly one of resistance by the Turkish Armed Forces against the US and the collaborative Turkish governments attempting to get Turkey to act as a satellite country to further American interests in the Middle East. Not only are the undue Sledgehammer and Ergenekon trials, which led to the arrest of many high-ranking military officers on allegations of coup-plotting against the AKP government, seen as an American conspiracy, but also the failed 2016 coup attempt.

As the logic of the narrative goes, the Turkish military’s objection to unconditional alignment with US interests during the post–Cold War era was a direct challenge to “US hegemony, furthering American interests behind the cover of a rule-based international order.” This desire to withstand perceived US unilateralism is the root cause of aspirations to build close ties with Russia and China.

Anti-American narratives also spread beyond the Eurasianists and echo among the secularist nationalist far left (the so-called ulusalcılar). Russia is generously spared criticism and NATO is perceived as the main culprit of the war. Security anxieties abound over the belief that the US is instigating the war as an opportunity to pressure Turkey to apply the Montreux Convention liberally in order to enhance the “NATO presence in Black Sea,” which would in turn harm “Turkish-Russian cooperation.”

For these actors, the denunciation of the US and NATO has deeper roots and reflects long-standing Cold War grievances. Accordingly, Turkey’s participation in NATO is seen as the core reason behind the growth of ultranationalism (associated with the Grey Wolves) and political Islam as the ideological currents that formed the backbone of anti-communist rhetoric as well as the organizational networks that undergirded anti-communist mobilization in Turkey. The original sin – the rise of anti-communism and the simultaneous fall of the Turkish left – according to this view continues to ensure that pro-NATO attitudes dominate Turkish politics, even today.

Even though the possibility of a growing American influence over Turkey through Erdoğan’s seeming rapprochement with NATO remains a concern for different factions of the far left, Ankara’s ongoing emphasis on Turkey’s autonomous foreign policy and Erdoğan’s recalcitrant, critical tone of the West appear to have partially eased these anxieties for the moment.

Electoral Calculations of the Mainstream Opposition

If the loudest voices within Turkey’s nationalist-Islamist ruling alliance and the far left converge on anti-Westernism in the wake of the war, the mainstream opposition for its part responded to the invasion by stressing the normative importance of Western institutions to Turkey’s democratization, thereby criticizing Turkey’s increasing dependence on Russia.

In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion, the Good Party’s (IYI) leader, Meral Akşener, demanded that Ankara “wriggle itself out of the asymmetric relationship that it has built with Russia, get rid of the S‑400s that have rendered Turkey fragile, immediately nationalize the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant [built and overwhelmingly financed by Russia], and terminate the Canal Istanbul project that might trigger regional instability.” This echoes the call to Erdoğan by the Republican People’s Party (CHP) leader, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, a day before the invasion to explain how Ankara was planning to use the S-400s.

At the center of the opposition’s denunciation of Ankara’s policy is Turkey’s drifting away from Western institutions, and with that democracy – defined in a formalistic way, with the focus being on the rule of law and institutions. Turkey’s decision to abstain from the Council of Europe vote on Russia’s suspension was met, for instance, with criticism from Kılıçdaroğlu. Similarly, Ali Babacan, the former Minister of Economy and the leader of the DEVA Party (DEVA) – an offshoot of the ruling AKP – called upon Ankara to put an end to its foreign policy vacillations and start acting responsibly, as “a dignified member of various European institutions” would and should do.

Similar criticism also resonates among business and former foreign policy elites. Simone Kaslowski, the head of the Turkish Industry & Business Association (TÜSİAD), for instance, emphasized in an article the importance of utilizing the current momentum toward “undoing the prevailing perceptions that Turkey moves away from the West and democratic principles, and that it is no longer a reliable member within NATO or the Council of Europe.” A former Turkish ambassador to the US, Namık Tan, argued in a similar vein, asking the government to signal to its Western allies its commitment to restoring the rule of law.

These remarks suggest that the mainstream opposition actors – within and beyond political parties – perceive the so-called West differently than Erdoğan and other actors within the ruling alliance do: Not only is it a geopolitical entity, but also a system of values. Kılıçdaroğlu echoed this view most explicitly in an interview with Reuters shortly before the invasion by noting that “NATO is not only a security institution, but also a guardian of democracy.”

However, such virtue-signaling is also tactical. The emphasis on democracy shaping the opposition actors’ thus far limited response to the Russian invasion is arguably a means to increase political pressure on Turkey’s ruling alliance. In their united stance against the weakening rule of law and diminishing institutional capacity under the Turkish presidential system, six of Turkey’s opposition parties – CHP, IYI, the Felicity Party (SP), the Democrat Party, DEVA, and the Future Party (GP) – are promoting a return to an enhanced version of the parliamentary system. The aim is to repair Turkey’s institutions and restore the rule of law through a firm commitment to the norms of the EU and other European institutions such as the Council of Europe.

Anti-Westernism: A Fault Line in Political Competition

This polyphony of responses to the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows that the war is throwing into sharp relief anti-Westernism as one of the main fault lines in domestic politics. For actors on the right and the left, the war has exposed what they see as the West’s double standards and hypocrisy, while accentuating the existential question about Turkey’s place in the world.

The mainstream opposition is itself not immune to the historical grievances and geopolitical aspirations concerning Turkey’s place in the world, despite its emphasis on revitalizing Turkey’s strategic relations with the West based on norms and democratic principles. This is one reason why challenging the anti-Western narratives that dominate the public debate is difficult. There are other reasons as well, however.

First and foremost, given that control over Turkey’s media landscape is heavily consolidated by the ruling AKP, countering such narratives is not easy and limited to a few alternative outlets. Secondly, Erdoğan himself also emboldens anti-Western narratives and deepens political rifts by cherry-picking his talking points, depending on the audience. Last, but not least, the mainstream opposition’s foreign and security policy outlook – particularly as it pertains to the implications of the Russian invasion for Europe and beyond – remains opaque, beyond the emphasis on their commitment to Western institutions and democratic principles.

The Future of EU-Turkey Relations in the Post-February 24 World

Various observers of Turkey have rightfully pointed out that the current moment offers an opportunity for the EU and Turkey to repair relations. This is not only because of the geopolitical gravity of the moment, but also because Erdoğan is increasingly walking a tightrope and eventually has to choose a side. Yet, how the EU-Turkey relationship will unfold is far from certain.

There are several reasons for this. Firstly, if mistrust of the West dominates the Turkish public debate, mistrust of Turkey will also not be absent in European capitals thanks to Ankara’s damaged record on democracy and its confrontational foreign policy. Not too long ago, in September 2020, Joseph Borrell, for instance, while addressing the EU Parliament’s plenary, listed Turkey, Russia, and China as re-emerging empires that “represent a new environment” for Europe. The reliability of Turkey as an ally in the eyes of European decision-makers has been significantly harmed. Moreover, public opinion in Europe about Turkey also remains critical.

Secondly, ambiguity about the outcome of the war, on the one hand, and the warm welcome in European capitals of Ankara’s mediation efforts, on the other, to a certain extent enable Turkey to continue hedging. As a middle-income country with a rapidly deteriorating economy, Turkey will likely carry on shielding its economy and security interests as long as it can. An outcome of this is a growing overconfidence in Ankara about its autonomous foreign policy.

Thirdly, it is not at all clear whether Erdoğan will converge with the European view that the invasion has surfaced the so-called free world’s confrontation against the unholy trinity of authoritarianism, militarism, and neo-imperialism. What is clear is that for Erdoğan and his domestic allies, the costs of leaving office are much higher than the costs of remaining in power. As Ryan Gingeras argues, this suggests that Erdoğan will prioritize his own political needs. If further rapprochement with the EU – and in general the West – benefits him more, he would not shy away from changing tack.

Yet, thirdly, and lastly, anti-Western narratives that are dominating the public debate are not easy to change in the short term. Pandora’s box is wide open, with the “clash of realities” cementing societal divisions. Erdoğan himself is a beneficiary of these divisions and actively cultivates them while speaking to domestic audiences. Moreover, the war itself also risks ultimately reinforcing anti-Western prejudices. The events since February 24 have clearly shown the ability of US leadership to revitalize the transatlantic alliance as well as the significance of this undertaking.

Recommendations for the EU

Notwithstanding, it is likely that in the short term Turkey’s NATO membership and its Association Agreement with the EU will continue to anchor it, geopolitically and economically, to the West – not least because of Turkey’s geographical location. Recent developments allude to this. While meeting with Italian and French leaders on the sidelines of the NATO meeting on March 24, Erdoğan brought up the issue of reviving defense cooperation talks on Eurosam’s SAMP/T missile defence system. Moreover, as Europe looks for means to decrease its energy dependence on Russia, Turkey is trying to reestablish itself once again as an energy corridor.

To what extent such geopolitical and economic anchoring is accompanied by a full strategic alignment with the EU over the mid- and long terms is still far from certain. This is mainly due to Turkey’s domestic political dynamics, but also the extent to which the EU (perhaps in coordination with the US) is willing to – and capable of – pushing relations with Turkey beyond the current geopolitical imperatives.

The EU’s political class is aware that a functioning relationship with Turkey is not a choice but an inevitability. This is due to the expansive economic and societal linkages between Turkey and the EU, the geographical proximity, the volatile security situation in the EU’s Southern Neighborhood, and more recently, the war in Ukraine. Yet, it is uncertain whether there is political will to push the relationship beyond a transactional framework.

But the EU could certainly play a positive role – even if it is limited in scope – toward building a sustainable relationship with Turkey based on mutual trust. Three issues require attention.

In the short term, the EU should demand (ideally in coordination with the US) that Turkey not undermine Western sanctions by stepping up economic cooperation and/ or by creating channels for Russian businesses to circumvent sanctions. Russia clearly sees Turkey as a strategic exit in overcoming the difficult economic situation that it has put itself in. In an interview with the Eurasianist daily Aydinlik, Andrey Buravov – Russian Consul General in Istanbul – voiced appreciation for Turkey not joining the sanctions regime and underlined the possibility of furthering economic relations between the two countries.

Secondly, the EU should actively work on sustaining internal unity in relations with Turkey. However, this is easier in theory than in practice given the various – and not necessarily overlapping – interests and threat perceptions of the member states. The last couple of years have clearly shown the divergences among member states in areas such as the Eastern Mediterranean, Syria, and Libya. The new reality on the ground requires a significant rethinking of these divergences and a search for effective avenues of cooperation in areas where there is overlap with Turkish interests. It is imperative that the EU not let bilateral tensions determine policy-making at the EU level. This requires, first and foremost, imagining a path toward compromise.

Thirdly, the necessity for close security and economic cooperation should not override the need to emphasize democratic norms. European policymakers have often prioritized stability over democracy in relations with authoritarian states. Relations with Russia are a stark example of the harsh reality that this approach does not bear fruit in the long term. It is time to adopt a strategic approach that is based on well-defined material and normative interests. Although the EU certainly cannot force Turkey to adopt democratic reforms, it can call out Ankara for its violations of human rights and rule of law. At the same time, the EU should also consistently raise the costs for taking unilateral action.

By: Dr. Sinem Adar – Associate at the Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) at SWP.

Source: CATS Network