Turkish democracy has reached a turning point.

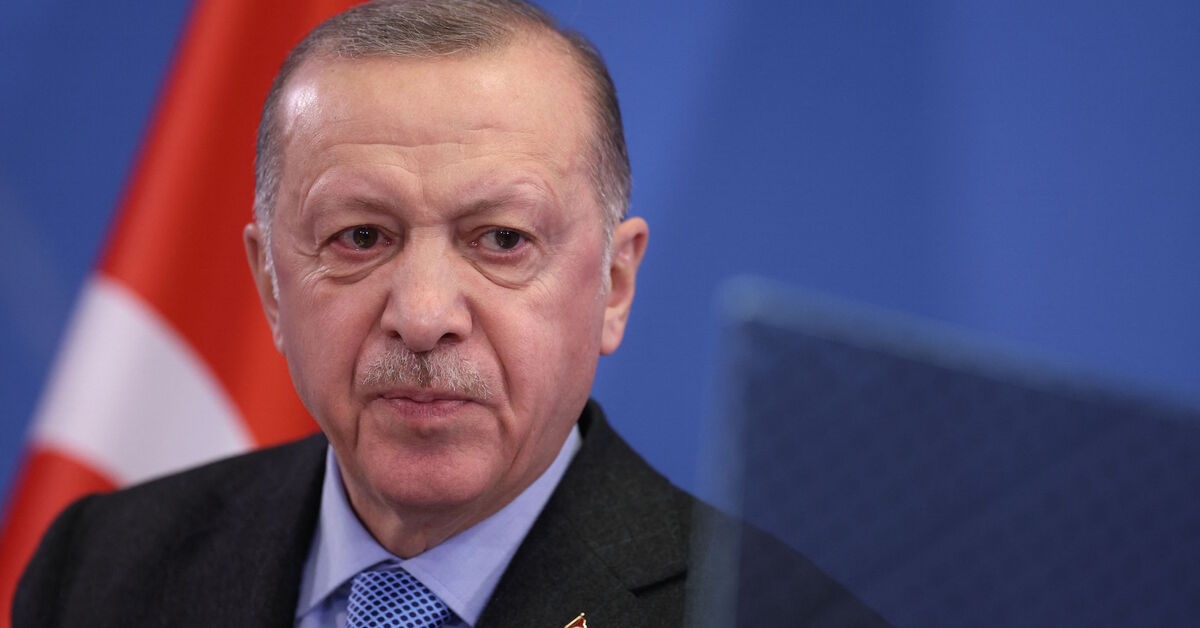

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s two-decade strongman rule has reversed his country’s progress toward a liberal society. On April 6, the Turkish president secured the passing of new electoral laws that will make it more difficult for smaller parties to enter Parliament, thereby inhibiting opposition coalitions and allowing him to use state resources to organize his own campaign events. These changes will make it harder for opponents to challenge Erdogan’s tightening grip on the Turkish electoral system.

As Erdogan prepares to run for reelection in the coming year, the importance of a vibrant and functioning Turkish civil society cannot be overstated. And it could not be more at risk.

These changes are the latest in a string of moves designed to dismantle what remains of Turkey’s once-promising democratic architecture. Erdogan’s authoritarianism has galvanized resistance in the form of an opposition coalition, the “Nation Alliance” led by the Republican People’s Party, while the dire state of the economic, social, and political situation in Turkey has catalyzed vibrant anti-government protests against inflation and for women’s rights and academic freedom.

The June 2023 elections will be a crucial test for pro-democracy voices in Turkey to rebuild their institutions. Their success will depend on their ability to bolster Turkey’s most at-risk hallmarks of free and fair elections: transparency, noninterference in voting, loser’s consent, and a free press.

They face an uphill battle. Erdogan’s regime has curtailed media access, undermined an open campaign process through bribery, intimidation, and violence, and is now seeking to obfuscate the voting process further through blatantly undemocratic reforms.

Erdogan’s campaign to degrade free media has made Turkey one of the world’s leading jailers of journalists, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. The government now controls 90% of the country’s media through regulatory bodies such as the High Council for Broadcasting, the Press Advertising Council, which allocates state advertising, and the Presidential Directorate for Communications, which issues press cards.

Under Erdogan, censorship laws have also been wielded as a weapon against online political discourse. A 2020 media law imposes requirements on social media platforms to remove content at the command of the Turkish government or risk punitive fines. Facebook and Twitter have submitted to Turkish government censorship, closing another avenue for healthy political discourse among Turkish voters.

Outside of media and online discourse, civil rights activism in general has been targeted by Erdogan’s regime. Reporters Without Borders has said that “questioning authorities and the privileged is now almost impossible” under Erdogan. Opposition parties are also increasingly persecuted by the regime, making effective political resistance increasingly difficult. In 2021, the state prosecutor argued that the pro-Kurdish HDP party was working toward breaking the “unity of the state.” The Constitutional Court forced the closure of the party and banned 451 elected officials. These most recent reforms take further aim at the opposition, legalizing the use of state resources when the president is campaigning for himself, while other ministers will be barred from doing the same.

In prior elections, Erodgan’s government has conducted systematic campaigns of intimidation. In Ankara, a local election was marred by claims of vote-rigging. Kurdish communities in particular face acts of intimidation and voter suppression. The government militarizes voting centers in the Kurdish region, claiming the security forces must “protect” against the threat of attacks by Kurdish terrorists. The People’s Democratic Party reported that political activities were banned from organizing in the streets. Under threat of intimidation by the state, Kurds are stripped of their right to vote freely.

In 2019, in what may prove a premonition of the 2023 elections, Erdogan showed that he is willing to interfere directly with democratic processes to try to cling to power.

He commanded that the Higher Electoral Commission rerun the Istanbul mayoral election after his party lost in spite of systematic irregularities that had actually worked in its favor. Despite his best efforts to intervene, his party also lost the rerun. The subsequent blowback showed it is not a foregone conclusion that Erdogan can get away with electoral interference in 2023.

The pandemic and the war in Ukraine have precipitated economic volatility and internal political turmoil. However, the free world cannot lose sight of the importance of Turkey’s elections, which will be watched by many of the world’s autocrats in waiting, keen to find out what they can get away with. Erdogan has systematically undermined every one of Turkey’s major democratic institutions to create a deeply skewed playing field. Holding his regime to account requires coordinated action from the international community, illumination of his thuggish tactics to suppress political minorities, and real consequences should he fail to make meaningful progress to restore civil discourse within Turkey.

Progress here means releasing imprisoned journalists to restore some semblance of a free press, allowing nongovernmental organizations to monitor the election effectively, and the cessation of hostilities against and censorship of opposing political voices. The international community should wield sanction power, as it has against Russia, turn off foreign military sales, and level severe consequences should Erdogan fail to achieve these objectives.

John Bolton is a former U.N. ambassador and White House national security adviser. He serves as an adviser for the Turkish Democracy Project.

Source: Washington Examiner