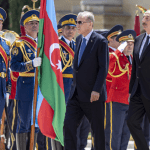

“Menendez being out of the picture is an advantage,” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan told reporters on September 26. Erdoğan said this just days after Senator Robert Menendez (D-NJ), who is facing federal charges of bribery, announced that he would step down temporarily as Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman.

Even if he does not resign—which many of his Democratic colleagues are now calling for him to do—Menendez’s departure from the powerful position seems to have already set in motion changes for the US-Turkey relationship. Throughout his time as chairman, Menendez was sharply critical of Turkey and more favorable toward pro-Greek and pro-Armenian causes.

What could Menendez’s departure as committee chair change? After all, the basic structure of the US-Turkey relationship remains the same. Turkey is, as it has long been, a strategically important but challenging ally for the United States. Concerns over human rights and democracy in Turkey, as well as over its relations with Russia, are widely shared among US lawmakers, but they are weighed against the country’s positive contributions to NATO (including with the Alliance’s second-largest military, which is conflict tested), its support for Ukraine, its pivotal position for regional energy security, and more.

This balanced spirit was encapsulated in a letter signed by a bipartisan group of twenty-seven senators in February. Addressed to US President Joe Biden, the letter stated the lawmakers’ opposition to the sale of F-16 fighter jets for as long as Turkey held up Sweden’s (and at that time Finland’s) accession to NATO. While it was not stated outright in the letter, a clear implication was that Turkey’s removal of this obstacle could pave the way for the United States to approve the sale of the aircraft.

Menendez was notably not among the letter’s signatories.

Since negotiations on Sweden’s accession began, it’s been widely assumed—but not openly stated—that the sale of F-16s would be a decisive factor in Turkey’s calculus.

Menendez’s departure means a potential change because as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee he held an effective veto over foreign arms sales, and he signaled his opposition to the sale of F-16s to Turkey early and often. He maintained this position even after the breakthrough at July’s NATO Summit in Vilnius, where Erdoğan indicated that he would send the ratification of Sweden’s accession to parliament. Asked after the NATO Summit about the issue, Menendez cited as a concern that Turkey’s parliament had not yet ratified Sweden’s NATO accession, but he also listed other grievances, including Turkey’s disputes with Greece. He appeared unwilling to budge on the issue, his reasons seemingly marshaled to justify a decision that had already been made.

Menendez’s departure as chair does not guarantee that the United States will now sell Turkey F-16s, but it does open space for a fresh look at the apparent deal on the table. Since negotiations on Sweden’s accession began, it’s been widely assumed—but not openly stated—that the sale of F-16s would be a decisive factor in Turkey’s calculus. For a year, diplomats on both sides took pains to deny the two issues were linked. However, Erdoğan abandoned all pretext on September 26, stating that “if they [the United States] keep their promises, our parliament will keep its own promise as well.” In a statement at the Vilnius summit, Turkey has committed to sending Sweden’s accession to parliament and working to ensure its ratification.

This apparent recognition that the F-16 sale and Sweden’s NATO accession vote in Turkey’s parliament are linked is a positive step. The risk now is that questions of sequencing or other issues devolve into a standoff in which Turkey is waiting for movement from Congress, while Congress waits for movement from Turkey’s parliament.

If Turkey cannot secure F-16s and instead looks to source its jets elsewhere, then the United States and Turkey could face a broader rupture in defense ties that may last a generation or more.

“I think it’s more likely it’s going to be approved,” explained House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Michael McCaul (R-TX) on September 27 about a possible deal on F-16s. But, he added, “We’re saying we’re not going to consider this if you’re going to play hardball against Sweden.” On September 28, new Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Ben Cardin (D-MD) said that he still had to talk to the Biden administration about the F-16 deal, “but there are other issues in addition to just NATO accession” that need to be resolved. The White House has been notably silent on the issue since Menendez’s departure. Nor did Biden meet with Erdoğan earlier in September at the United Nations General Assembly in New York, following a pattern of minimizing leader-to-leader contact with the Turkish president compared with previous administrations.

Time is running out. Turkey’s parliament returned from recess this week, and the longer the situation goes without progress, the more paralyzed and corrosive it could become. The Biden administration, through its diplomats and its outreach to Congress, should work diligently to overcome this dilemma.

Beyond the singular issue of Sweden’s accession—which has been awaiting final ratification from Turkey and Hungary for more than a year—the F-16 deal holds strategic importance for the US-Turkey relationship. Defense cooperation has traditionally been a main cornerstone of bilateral relations between the United States and Turkey. That cooperation, however, has been damaged at the strategic level by disagreements over policy toward Syria and imperiled further by Turkey’s purchase of the Russian S-400 air-defense system in 2017. The United States responded to the purchase by removing Turkey from the F-35 program in 2019 and imposing sanctions on Ankara in 2020. If Turkey cannot secure F-16s and instead looks to source its jets elsewhere, then the United States and Turkey could face a broader rupture in defense ties that may last a generation or more. Such an outcome would not be in the strategic interests of Turkey or the United States.

By: Grady Wilson – associate director at the Atlantic Council IN TURKEY. Follow him on Twitter @GradysWilson.

Source: Atlantic Council