At a landmark international summit in Colombia aimed at confronting Israel’s military campaign in Gaza, Turkey chose not to sign a six-point action plan endorsed by a dozen countries, citing legal concerns that could impact its ongoing maritime disputes in the Aegean Sea. The Bogotá conference, held July 15–16 and co-hosted by Colombia and South Africa under the Hague Group umbrella, brought together over thirty nations intent on crafting a unified legal and diplomatic front in response to Israel’s continued bombardment of Gaza and military aggression in the occupied Palestinian territories.

The Hague Group pursues several interrelated and strategically significant objectives aimed at strengthening international accountability mechanisms. A major catalyst for its formation came on July 19, 2024, when the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued a landmark advisory opinion declaring that Israel’s prolonged occupation of Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem constitutes a violation of international law and amounts to a de facto annexation. This legal assessment not only reaffirmed the illegality of Israeli policies in the occupied territories but also laid the groundwork for potential international action.

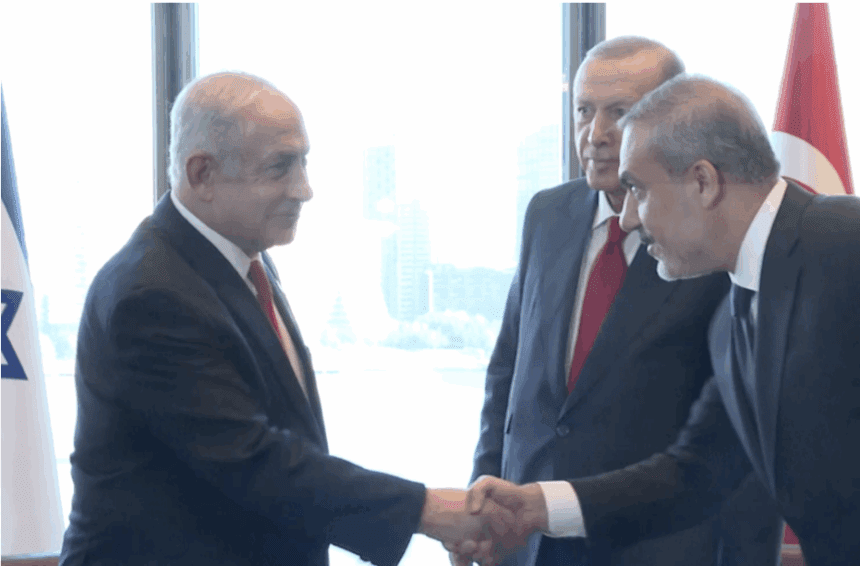

Building on this momentum, the International Criminal Court (ICC) took an unprecedented step on November 21, 2024, by issuing arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant. Both were charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity in connection with Israel’s military operations in the Gaza Strip. These developments marked a turning point in the legal framing of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, elevating it from a matter of political dispute to one of judicial urgency.

The above-mentioned summit produced two outcomes: a general political declaration condemning Israel’s conduct in Gaza and a more forceful six-point action plan aimed at cutting off military and economic support for Israel’s occupation. While Turkey signed the political statement, it refused to join the twelve nations—including South Africa, Iraq, Indonesia, and Cuba—that committed to concrete legal and logistical measures.

These include halting all arms transfers to Israel, denying port access to ships delivering military cargo, reviewing public contracts tied to Israeli companies complicit in the occupation, and applying universal jurisdiction to prosecute war crimes in Gaza. The document sets a clear deadline: by September 20, 2025—coinciding with the opening of the UN General Assembly—additional states are expected to endorse the plan, aligning their domestic policies with international law and human rights norms.

Twelve of the attending countries signed the Bogotá Declaration — notably, Turkey was not among them. CHP (Republican People’s Party) leader Özgür Özel commented: “They fled from Colombia without signing the action plan. They were afraid of [U.S. President Donald] Trump.”

Turkey’s absence from the signatory list raised eyebrows—not least because Ankara has long positioned itself as one of the loudest champions of the Palestinian cause in the Muslim world.

Legal Justification or Convenient Pretext?

Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan defended Ankara’s refusal to sign, pointing to the action plan’s grounding in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)—a treaty Turkey has refused to ratify due to its maritime boundary disputes with Greece. Fidan argued that some of the plan’s language risked setting legal precedents that could weaken Turkey’s claims in the Aegean Sea, where the status of Greek islands and maritime borders remains a deeply contested issue.

In a televised interview following the summit, Fidan emphasized that the government’s decision was not due to a lack of support for the Palestinian cause but stemmed from specific legal and geopolitical concerns. “We support the spirit and the aim of the declaration,” Fidan said, “but the wording of the six-point plan introduces legal commitments that reference UNCLOS—an agreement Turkey has not signed, largely due to our maritime disputes in the Aegean.”

According to his statement, Turkey did join the declaration with a reservation. Since Turkey is not a party to UNCLOS, it supposedly wanted to emphasize that the mention of UNCLOS in the declaration did not alter its official position. That’s Fidan’s claim.

“The text [Bogotá Declaration] was sent to us. We reviewed it, added our reservation regarding UNCLOS [United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea], consulted our Director General of International Law, spoke with relevant institutions, and concluded that there was no issue with recognizing the document as long as we added our reservation. In fact, we usually lead the drafting of such texts.”

However, the final version of the declaration — published on the South African Foreign Ministry’s website — lists the countries that joined with reservations, and Turkey is not one of them. For example, Iraq and Libya are noted as having signed the declaration with the reservation that they “do not recognize the State of Israel.” This means their representatives said, “Signing this document does not imply that we recognize Israel as a state.”

Turkey’s concerns over UNCLOS are not new. Since the 1990s, Ankara has warned that the 12-nautical-mile territorial waters allowed by UNCLOS, if applied around Greek islands, would effectively turn the Aegean into a “Greek lake,” restricting Turkish naval and commercial access. Because UNCLOS does not allow for reservations or selective adoption, Turkey has declined to become a party.

While this explanation may seem technically plausible, many view it as a diplomatic smokescreen. The action plan’s core objectives—blocking arms sales and ending corporate complicity in war crimes—could have been implemented without requiring Turkey to adopt any maritime boundaries or legal obligations. Instead, Ankara opted to highlight a peripheral legal concern over a central moral and humanitarian crisis.

Hypocrisy and Interests Over Ethical Commitments

Critics say Turkey’s refusal to sign the plan reflects a deeper contradiction in its foreign policy: the gulf between its populist, pro-Palestinian image and its unwillingness to jeopardize economic or strategic interests. Despite the Gaza war, Turkish-Israeli trade has continued largely uninterrupted. The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, which runs through Turkish territory, remains one of Israel’s key sources of crude oil. Israeli imports of petroleum derived from Azerbaijan via Turkey have increased since the start of the conflict in October 2024.

Moreover, Ankara has not moved to suspend defense industry ties or impose targeted restrictions on companies engaged with the Israeli government. Ports remain open, trade routes active, and diplomatic backchannels functioning—despite the Erdoğan administration’s claims of “solidarity with Gaza.”

The result is a foreign policy that appears increasingly performative: strong on slogans, weak on enforcement.

Pattern of Symbolism Without Substance

This is far from the first time Turkey has adopted a posture of moral leadership while avoiding meaningful costs. Following the Mavi Marmara flotilla raid in 2010, Turkey downgraded diplomatic relations with Israel, only to quietly restore them years later. During past Israeli operations in Gaza, Ankara has called for international tribunals and embargoes—yet rarely followed through with binding legislation or policy shifts.

For domestic audiences, especially within Erdoğan’s Islamist-conservative base, the symbolism of “defending Palestine” has electoral appeal. But in the international arena, where accountability demands more than declarations, Turkey’s reluctance to align with enforcement mechanisms continues to undermine its credibility.

While countries like South Africa and Malaysia have committed to using their domestic legal systems to prosecute war crimes and sever complicit trade links, Turkey remains mired in legal hesitations and geopolitical calculations. Its repeated invocation of UNCLOS—while continuing trade and energy cooperation with Israel—raises questions about whether Ankara’s true concerns lie with international law or domestic political optics.

Credibility on the Line

The Hague Group’s initiative marks one of the most coordinated attempts yet by Global South and non-aligned nations to use legal tools against Israel. UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese praised the six-point plan as “a lifeline for a people under relentless assault” and a long-overdue response to what she called “the paralysis of international institutions.”

Observers note that the gap between what Turkey says and what it does has become harder to ignore. If Ankara genuinely wishes to position itself as a leader in the global South on matters of justice and human rights, symbolic declarations will no longer suffice. The Hague Group’s initiative has set a new bar for meaningful international action—and Turkey, for now, has chosen to stand just outside the circle.

The upcoming September deadline offers one last opportunity for Ankara to match its words with action. If it fails to do so, its pro-Palestinian messaging risks being viewed not as principled diplomacy, but as political theatre—loud, calculated, and ultimately hollow.

By: News About Turkey (NAT)