On July 11, 2025, a small band of Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) guerrillas gathered at the mouth of Jasana Cave near Sulaymaniyah in northern Iraq for a ceremony few imagined possible. Clad in fatigues, thirty fighters – men and women – solemnly placed their AK-47 rifles and bandoliers into a large metal cauldron and set them aflame. The flames that consumed these weapons symbolized the end of a 40-year armed insurgency that had cost over 40,000 lives and scarred Turkey’s social fabric. Kurdish commanders like Bese Hozat declared the disarmament a voluntary step taken “in goodwill” to pursue freedom and democracy through politics rather than guerrilla war.

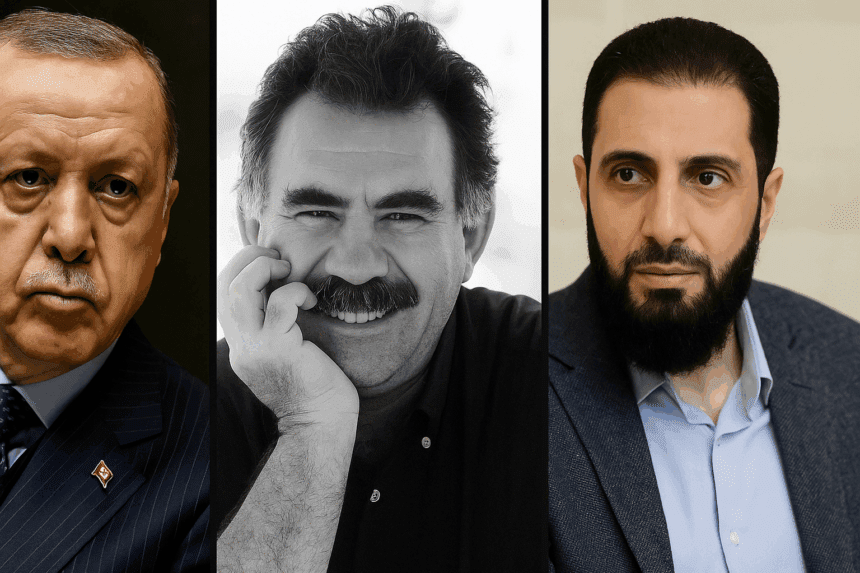

This remarkable scene was set in motion by an even more astonishing intervention from the PKK’s founder and imprisoned leader, Abdullah Öcalan. From his island prison, Öcalan had issued a historic call in February for his fighters to lay down their arms and dissolve the PKK entirely. After decades as Turkey’s arch-enemy, Öcalan now proclaimed that armed struggle had run its course and that Kurds’ future lay “within [the] democratic politics and law” of the Turkish state. In a video message – his first public appearance since 1999 – the 77-year-old Öcalan framed disarmament not as surrender but as a “voluntary transition” and a “historical gain” for his movement.

Erdoğan’s ‘Turkish–Kurdish–Arab Alliance’ Rhetoric

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan lost no time in seizing the narrative of this peace. The very next day, he announced the creation of a parliamentary commission – composed of his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), its ultranationalist ally the MHP, and the pro-Kurdish Democracy and Equality Party (DEM) – to oversee the PKK’s transition from combat to politics. More dramatically, Erdoğan declared that history had turned a new page and unveiled a grand vision of regional unity. Turkey’s future, he proclaimed, would be built on a “Turkish–Kurdish–Arab alliance,” a partnership of three peoples who, he noted, “won victories in history when they united on the basis of Islam”. In an emotive flourish, he recited a roll call of “common cities”: “Damascus is our common city. Diyarbakır is our common city. Mardin, Mosul, Kirkuk, Sulaymaniyah, Erbil, Aleppo, Hatay, and Istanbul are our common cities.” Each name invoked the geography of the defunct Ottoman Empire, linking Turkish heartlands with Kurdish and Arab lands.

Erdoğan’s rhetoric deliberately echoed historical touchstones. The litany of shared cities harked back to the 1920 Misak-ı Millî (National Pact) – the Ottoman parliament’s last vision of a post-WWI order – which claimed as Turkish patrimony all Ottoman territories with Muslim majorities. By invoking cities like Mosul, Aleppo and Kirkuk, Erdoğan appeared to be reviving that irredentist dream in modern garb. Indeed, as some observers note, the borders Turkey failed to secure after World War I now seemed to be reappearing “by stealth, not diplomacy” in Erdoğan’s narrative. At the same time, the President’s emphasis on Islamic unity – “when [we] are united, then the Turk exists, the Kurd exists, the Arab exists” as he put it – channeled the spirit of Sultan Abdülhamid II’s pan-Islamism. Much like Abdülhamid’s 19th-century appeal for Muslim solidarity to preserve a crumbling empire, Erdoğan’s “Jerusalem Alliance” (as he dubbed it) calls Turks, Kurds and Arabs to come together as an ummah, healing the divisions imperial powers sowed among them. In Erdoğan’s telling, foreign plots had pitted brothers against each other – “the Arabs stabbed us in the back, the Kurds tried to divide us,” as Turkish ultranationalists often claim – and led to defeat and humiliation in past centuries. Now, by restoring Muslim brotherhood, Turkey could reclaim leadership in the region and prevent further “defeats” like the loss of Jerusalem or the Mongol and Crusader invasions Erdoğan invoked.

Devlet Bahçeli, leader of Turkey’s far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and a key political partner of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has also ignited widespread debate after proposing that one Kurdish and one Alevi figure be appointed as vice presidents. hiss proposal was first shared during a closed-door meeting of the MHP’s central executive board on July 18 and later confirmed in a written statement released on Monday. He framed the idea as a way to help heal Turkey’s long-standing ethnic and sectarian divisions, stating that the time had come to strengthen national unity through inclusive representation.

Crucially, Erdoğan’s vision is framed not in the language of liberal democracy or equal citizenship, but in civilizational and religious terms. He pointedly argued that Islamic partnership was the source of past glory, sidestepping the secular republican ideals that modern Turkey was founded on. This has not been lost on observers. In fact, U.S. Ambassador Tom Barrack – a close ally of the Trump administration and now Washington’s special envoy to Syria and Lebanon– openly praised the Ottoman Empire’s millet system as a model for managing ethnic diversity, implicitly endorsing Erdoğan’s nostalgic framing. The Ottoman millet system, which governed diverse communities through religious autonomy, is held up as historical proof that Turks, Kurds, and Arabs can coexist under a single political roof without losing their identities. Ambassador Barrack’s musings on Ottoman pluralism were strikingly in harmony with Erdoğan’s rhetoric, a congruence that Turkish commentators found far from coincidental. Erdoğan appears to be uniting Turks and Kurds not through frameworks of citizenship, democracy, or human rights, but rather through the lens of religious solidarity. This ideological pivot raises a thorny question: Is the “Three-Nation Vision” a genuine effort at multicultural unity, or a clever repackaging of neo-Ottoman ambitions?

Geopolitical Winds: Opportunity Amid Chaos

The timing of Erdoğan’s grand initiative is hardly accidental. It comes against the backdrop of turbulent geopolitical shifts that have unsettled the Middle East in the past two years. The most dramatic was the fallout from the Israel–Hamas war of 2023 and its regional domino effect. In the year following Hamas’s October 2023 attack and the Gaza war, Israel expanded its military campaigns – striking Hezbollah in Lebanon and even launching air assaults on Iran. In a stunning turn of events that December, Syria’s Russian- and Iranian-backed ruler Bashar al-Assad was toppled by a coalition of rebel forces led by the Islamist Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) – forces covertly advised by Turkey and tacitly supported by Western powers. A new regime under rebel leader Ahmed al-Sharaa took power in Damascus, openly aligning with Ankara and even expressing openness to joining the U.S.-brokered Abraham Accords with Israel. This regime change, effectively removing Iran’s foothold in Syria, dramatically increased the influence of both Turkey and Israel in shaping Syria’s future.

For Turkey, these convulsions presented both peril and promise. On one hand, the spectre of maps being redrawn in blood – as Erdoğan grimly described the regional chaos – threatened to spill into Turkey’s own neighborhood. Ankara watched warily as Israel asserted regional dominance and even speculated that Israel might court the Kurds as new proxies. Turkish strategists feared the PKK or its Syrian offshoots could become an Israeli-backed pawn, reigniting Kurdish separatism with outside support. On the other hand, the chaos opened a strategic “opportunity,” in Erdoğan’s words, for Turkey to press its advantage. With Assad gone and Washington hungry for an exit from Syria, Ankara moved swiftly to shape the endgame. Turkey had already established itself militarily in its near abroad: since 2018, it has occupied swathes of Kurdish-led northern Syria and built dozens of bases up to 40 miles deep into Iraqi Kurdistan, ostensibly to fight terrorism. Now, Turkish officials leveraged their cooperation in Syria’s regime change to secure U.S. backing for a broader regional deal. President Donald Trump’s second administration proved amenable. Eager to isolate Iran and reduce America’s military responsibilities, Trump supported Turkey’s peace initiative with the Kurds, which had been initiated by the previous US administration. He viewed this as an opportunity to stabilize Turkey by dismantling the PKK forces, integrating the PKK-aligned Syrian Kurdish forces, and solidifying a bloc of Turks, Kurds, and Sunni Arab allies against Iran and Russia. Ultimately, this strategy could also be leveraged against China in the long term.

Ambassador Barrack’s role in this geopolitical choreography has been pivotal. In negotiations from Ankara to Qandil, he delivered a clear message: with Assad gone and a new, Turkey-friendly government in Damascus, the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) must now come to terms with Syria’s reintegration. “There’s one country, one nation, one people, and one army,” Barrack declared in a pointed interview, effectively telling Syria’s Kurds to abandon dreams of autonomy. The United States, he said, now backs “one Syria, one army, one government” – a stark reversal after years of supporting Syria’s Kurds as autonomous partners. Indeed, within weeks of the PKK disarmament, American envoys convened talks in Damascus aiming to fold the 100,000-strong SDF into the new Syrian national army, under Turkey’s watchful eye. The Trump administration’s alignment with Ankara was underscored by President Erdoğan himself: he noted with satisfaction that “Barrack-led Americans… held talks in Syria” and delivered “very positive” messages supporting Turkey’s deal with the PKK. In short, global powers have lent their weight to Erdoğan’s Three-Nation Vision not out of altruism but strategic calculus. For Washington and even Israel, placating Turkey and neutralizing Kurdish militancy serve the broader goal of consolidating a pro-Western, anti-Iran order across the Middle East. For Erdoğan, this backing provides international legitimacy to what might otherwise be seen as a neo-Ottoman adventure.

Yet there is also a competitive undercurrent: Turkey’s regional ambitions do not always neatly align with those of its allies. Even as Ankara cooperates with Israel and the U.S., it jockeys with them for influence. Erdoğan’s very invocation of a Muslim triune alliance is, in part, a rebuttal to Israel’s regional clout. He argued that Israel could perpetrate its onslaughts in Gaza and beyond only because “Turks, Kurds and Arabs [were] divided,” implying that a united front could have thwarted Israeli aggression.. This glosses over Turkey’s own covert role in aiding Israel – Turkish bases and intelligence facilitated Israeli strikes on Iran, a fact Erdoğan omits. Still, the notion of a revived Muslim partnership allows Ankara to pose as a champion of the Palestinian cause and regional justice, even as it partakes in the very power politics it decries. It is a delicate balance: Turkey is both a willing accomplice in U.S.-Israeli designs to “reshape” the Middle East and an independent actor seeking to secure its “share of the spoils” in this imperial reordering. Notably absent from Erdoğan’s alliance are the Persian Iranians – fellow Muslims pointedly left out of his ummah rhetoric. In the Three-Nation Vision, Iran is the other, the excluded rival, which lays bare the realpolitik beneath the rhetoric of brotherhood.

Negotiated Surrender or Strategic Shift? Öcalan and the Kurdish Question

Central to this grand bargain is the figure of Abdullah Öcalan, whose sudden re-emergence has left many analysts pondering his motives. After over two decades in solitary confinement, the PKK leader’s decision to effectively liquidate his own militant legacy was as crucial as it was controversial. It was Devlet Bahçeli, the firebrand nationalist MHP leader known for ultra-hardline views on Kurds, who unexpectedly set the stage. In October 2024, Bahçeli publicly suggested that if Öcalan renounced violence and ordered the PKK to disband, the state “could allow him to address parliament” or even transfer him to house arrest. This startling overture from an erstwhile hawk signaled that Ankara’s highest circles were ready to deal. Shortly after, Turkish authorities permitted a delegation from the new pro-Kurdish DEM Party to visit Öcalan in his island prison. By late February 2025 the aging guerrilla chief released a letter to the nation. In it, he not only called on the PKK to disarm and disband, but went so far as to declare his movement’s “historical and political bankruptcy” and propose “integration with the state”. It was a remarkable self-critique – essentially admitting that the PKK’s armed struggle had failed to achieve Kurdish freedom and that a new path within Turkey’s legal framework was the only way forward.

In recent decades, he had already shifted the PKK away from separatist nationalism toward a platform of “democratic confederalism” and Kurdish autonomy within existing states. To some extent, calling off the armed struggle and urging Kurds to work “within Turkey’s democratic framework” was consistent with the direction Öcalan had been heading. There are even reports that Öcalan was alarmed by the notion of the PKK being exploited in great-power conflict. Having once received training from Palestinian militants and fought Israeli forces in Lebanon in the 1980s, Öcalan is said to have told visitors he “wouldn’t allow his group to be used as a proxy by Israel” in any quest for regional domination

Öcalan’s endorsement gave the green light that PKK commanders in the Qandil Mountains dared not ignore. Within days, the guerrillas announced a unilateral ceasefire, and by early May the organization convened an extraordinary congress to vote itself out of existence. The authority Öcalan still wielded over the PKK rank-and-file, despite 25 years behind bars, cannot be overstated. His blessing was the sine qua non of disarmament – a fact Erdoğan himself tacitly acknowledged by allowing Öcalan’s video message to be broadcast nationwide For the Turkish state, Öcalan’s cooperation was a diplomatic triumph: the very man once demonized as “Turkey’s Osama bin Laden” had become the key to ending Turkey’s longest-running war.

Öcalan’s volte-face has drawn criticism from Kurdish nationalists past and present. By abandoning the PKK’s foundational goal of an independent (or at least autonomous) Kurdistan and urging Kurds to integrate into the very state that long denied their existence, has Öcalan betrayed his people or saved them? Some argue he has effectively helped Ankara fulfill its National Pact ambitions – implementing Article 1 of that 1920 pact, which opposed any separation of Ottoman Muslim lands. The “mountain Turks” (as the republic once derisively called Kurds) are now to be subsumed as Muslim brethren within Turkey, rather than recognized as a distinct nation. Perhaps Öcalan genuinely believes this will bring Kurdish people a better life after generations of war. Or perhaps, as skeptics contend, he has been misled by Ankara’s promises.

Democracy and Its Discontents

The 2025 accord has been hailed as a statesmanlike breakthrough. World leaders and the United Nations lauded Turkey for ending a conflict that had burdened its economy by an estimated $2 trillion over four decades. Even Turkey’s domestic opposition initially offered measured praise. “We welcome the terrorist organization’s symbolic step of laying down arms today,” said Özgür Özel, leader of the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP). Yet Özel – and many Kurdish activists – have also raised pointed questions about the contradictions at the heart of Ankara’s peace. Erdoğan, after all, has built his recent political career on crushing the Kurdish political movement and stifling dissent. How sincere is his conversion to inclusion and “brotherhood”?

Speaking in Parliament, Özel applauded the end of violence but lambasted the government’s ongoing repression of legal Kurdish political expression. “An environment in which trustees are appointed to replace mayors, investigations criminalizing Kurdish participation in municipal councils continue, elected politicians are imprisoned unlawfully, and democratic competition is crippled is the main enemy of social peace,” he warned. Indeed, in the very week that Erdoğan extended an olive branch to the PKK’s political heirs, dozens of Kurdish mayors and legislators from the predecessor to the DEM Party remained behind bars – victims of terrorism charges in dubious trials. The pro-Kurdish HDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party), which the new DEM Party effectively replaced, had seen hundreds of its officials jailed or removed by government fiat in recent years. Even as Erdoğan now courts Kurdish support, he has not freed the HDP’s imprisoned former leader Selahattin Demirtaş, nor offered restitution for thousands of Kurds blacklisted or exiled during the conflict. This dissonance was summed up by CHP’s Özel, who noted the absurdity of claiming to “democratize” while still treating basic Kurdish political activity as a criminal offence.

Critics also note that Erdoğan’s new narrative of Muslim unity pointedly centers Sunni Islam – a framing that alienates many Alevis, secular Turks, and non-Muslim minorities, and even rings hollow for Kurdish Alevis and Yazidis. Özel himself rejected the idea of a Turk–Kurd–Arab pact built “around the idea of an ummah, Sunni sectarianism, and Islamism,” accusing Erdoğan of crafting a fictional coalition for political gain rather than genuinely embracing pluralism. For secular opposition figures, Erdoğan’s talk of unity in Islam smacks of an attempt to paper over Turkey’s democracy deficit with feel-good nostalgia.

Even some within the Kurdish movement are cautious. The DEM Party, while participating in the disarmament process, has publicly ruled out a formal political alliance with Erdoğan’s ruling bloc. Its co-leaders insist that real peace requires deep democratization – constitutional guarantees of cultural rights, an end to authoritarian rule, and even a new definition of citizenship beyond ethnic Turkishness. They have subtly signaled that they might align with the opposition rather than be co-opted as Erdoğan’s token Kurds. This highlights a fundamental tension: will the Kurdish question be resolved by genuine power-sharing and liberties, or by co-optation and window-dressing?

So far, Erdoğan’s actions suggest the latter. In the wake of the PKK’s dissolution, he immediately leveraged the Kurdish rapprochement to entrench his own power. In March 2025, as protests broke out over the arrest of Istanbul’s popular mayor, Ekrem İmamoğlu. Erdoğan pointedly invoked his deal with Öcalan to dissuade Kurdish groups from joining the demonstrations. The tactic worked – Kurdish turnout in anti-government protests was muted, giving Erdoğan breathing room. He then moved further against his secular rivals in the recent months by arresting dozens of opposition CHP mayors across Turkey for alleged corruption.

Even the promised reforms for Kurds remain uncertain. Erdoğan has dangled the prospect of cultural rights expansions – allowing Kurdish-language education, returning seized village names, and infrastructure investment in Turkey’s long-neglected Kurdish southeast. He has hinted at legal changes to facilitate the safe return of PKK fighters from exile in Iraq and amnesty for those who lay down arms. Such steps would indeed be groundbreaking if fully realized, giving Kurds opportunities they have been denied for generations. Despite some measures being proposed, skepticism remains about their effectiveness: any concessions might be superficial, offering only limited cultural and linguistic recognition that fails to achieve true equality.

Imperial Fantasy, Pragmatic Pact, or New Dawn?

As Turkey, the Kurds, and their Arab neighbors embark on this uncharted path, the “Three-Nation Vision” remains a work in progress – one laden with both grand promise and profound ambiguities. Is Erdoğan’s tri-national alliance an imperial fantasy, a nostalgic bid to resurrect Ottoman-era influence under Ankara’s tutelage? Or is it a pragmatic alignment of interests born of crisis, likely to persist only so long as it serves the power players involved? Might it even contain the seeds of a genuinely transformative political reconfiguration for the post-conflict Middle East?

From one angle, the cynics have a compelling case. Erdoğan’s language about common cities and shared destinies can be read as thinly veiled irredentism, laying political groundwork for Turkey’s expanded influence in northern Syria and Iraq, supported by the U.S. By positioning Turkey as the benevolent patron of Kurds and Sunni Arabs, Erdoğan is arguably seeking to legitimize a long-term Turkish presence. The historical references to the National Pact are not mere flourishes; they telegraph a claim that lands lost in the early 20th century rightfully belong in Turkey’s orbit. In this sense, the Three-Nation Vision could be a 21st-century update of “Neo-Ottomanism,” fulfilling what Turkish expansionists have dreamed about since the republic’s founding. The presence of devoutly Islamist, nationalist figures like Bahçeli in the process underscores that this is no liberal peace – it is a deal between elites to consolidate power. And for Erdoğan personally, the alliance with a Kurdish party is a means to an end: securing enough support to rewrite the constitution and extend his rule beyond the term limit of 2028. By aligning with DEM’s 56 MPs, Erdoğan moves closer to the supermajority required to amend the constitution and could effectively establish a lifelong presidency and a dynastic autocracy.

And yet, it would be too facile to dismiss the Three-Nation Vision outright as a cynical ploy. The very fact that guns have fallen silent after 47 years is profoundly transformative. However flawed the terms, this peace opens political space that simply did not exist before. There is cautious hope in Diyarbakır and Sulaymaniyah that perhaps this time will be different – that Ankara will follow through with concrete improvements in Kurdish lives, from language rights to economic development. The prospect of Kurds, Turks, and Arabs cooperating also carries transformative potential for a region shattered by sectarian and ethnic divides. If nurtured sincerely, a tripartite understanding could help stabilize war-torn Syria and Iraq. Trade corridors that were once battle zones – a railway from Turkey to the Persian Gulf, or highways across Syria – can now be envisioned with less fear of sabotage. Some optimists even muse that a new regional order might emerge, one where historic rivals become partners. As one commentary noted, for the first time in decades Kurds across Turkey, Syria, and Iraq may finally glimpse a future without war, and Turkey itself seems willing to work with Kurdish leaders in shaping that future. These are developments few thought possible just a few years ago.

Ultimately, the Three-Nation Vision might be all of the above: part imperial nostalgia, part pragmatic crisis management, and part genuine paradigm shift. Much will depend on how each stakeholder chooses to carry it forward. Will Erdoğan lean into the magnanimous, inclusive role he has sketched, or revert to authoritarian form once he has secured his objectives? Will Kurdish leaders like those in the DEM Party capitalize on this opening to push for lasting reforms, or find themselves outmaneuvered and their constituency demoralized? And will Arab actors – from the new Damascus government to Iraqi Kurds and others – truly embrace a shared regional framework, or balk if they perceive it as Turkish domination in new clothes?

As of today, these questions remain unanswered, hanging in the air much like Erdoğan’s evocative metaphors. Is this alliance a sturdy bridge to a post-conflict Middle East, or a mirage that will fade once real-world interests collide? The “Three-Nation Vision” sits delicately between history and strategy, borrowing grandeur from the past to address the urgencies of the present. It is a bold experiment in aligning identities that a century of nationalism sought to keep apart. Should it succeed, even partially, it could begin to mend some of the deepest fractures in the region’s modern history. Should it fail or be betrayed by its architects, it may go down as yet another grand illusion – an imperial daydream cloaking old-school power politics. In the end, the legacy of this moment will be determined not by the rhetoric of unity in Ankara’s halls, but by the reality on the ground: whether the peoples of Turkey, Kurdistan, and the Arab world truly feel a new sense of common cause, or simply find themselves pawns in a freshly dealt game of empires. Only time will tell whether this uneasy marriage of opportunism and idealism yields a lasting peace – or proves to be, in the cold light of hindsight, a fleeting truce dressed up in the finery of a new Ottoman tale.

By: News About Turkey (NAT)