Former Lt. Cdr. Cafer Topkaya, a purged and jailed Turkish naval officer who was assigned to NATO prior to a failed coup in Turkey, has told Deutsche Welle that he is coming out of the shadows to relate what he experienced “for those who can’t meet the press, who can’t meet with journalists, who can’t even meet with their lawyers now that they are in prison [in Turkey] and can’t prove their innocence.”

The lifelong naval officer said he is “not afraid of [Turkish President Recep Tayyip] Erdoğan or his partners … or Turkish intelligence” and wants the West to know what is happening inside Turkey.

Topkaya is one of thousands of Turkish military officers who were summarily condemned by Erdoğan as being supporters of US-based İslamic cleric Fethullah Gülen, who the president accuses of instigating a failed 2016 coup from exile in Pennsylvania. In the massive purges that are still taking place in Turkey, those military personnel trained and stationed in Western countries became particular targets. Erdoğan ordered virtually all of them back to Ankara to face “questioning,” a euphemistic term for what effectively meant imprisonment in most cases.

Many chose not to go and to become stateless in their countries of residence after the Turkish government canceled their passports and their salaries. But when he got summoned to an “urgent meeting” in Ankara in October 2016, Topkaya said he felt obliged to follow those orders out of a deep sense of duty. He surmised even if there would be routine questions to answer, it would quickly become clear that he had nothing to do with the coup attempt or the Gülenist movement.

“I have never been close to the Gülen movement,” Topkaya explained. “I’m a secular person. I was educated in the Western style. I respect all religions, all ideologies but I’m not a member of any of them.” He felt secure in his record of being a lifelong Navy officer with a so-called cosmic top-security clearance, the highest granted by NATO. His wife Meşkure shared his reasoning and wasn’t worried as the family kissed him goodbye for what they thought would be two days.

They would not see each other again for more than 16 months. The “meeting” had been a ploy, and Topkaya was trapped in the Ministry of Defense, his official pass deactivated so police could swoop in and drag him away. His own former Turkish colleagues now labeled him a “terrorist” and said he had been operating a Twitter account that insulted Erdoğan although he protested he had never even had a Twitter account at that point.

In the re-purposed gymnasium where he was first held and then later in the infamous Sincan Prison, Topkaya said he slept on a concrete floor for 12 days in the same clothes and was given inadequate food alongside other high-ranking military personnel, academics, judges, civil society leaders and even medical professionals. But he said he personally escaped the harsh physical and mental torture others experienced, wincing as he described the interrogations suffered by inmates whose bruised and battered bodies he saw afterwards.

One officer who refused to accept the charges of conspiring in the coup repeatedly had his wife dragged into interrogations and his young children threatened, Topkaya recalled; another had been forced to sign a confession while seated in a chair that delivered electric shocks.

At first, Topkaya kept a timeline in a notebook he used as a diary, writing “Brussels” at the end of one line and marking off what he presumed would be a very few days until he was back there. “I was waiting for release,” Topkaya recalled. “Not that day, but in a few days I believed I would be free.” After the 39th mark, he stopped counting.

When first brought before a prosecutor, Topkaya remembers finding it difficult even to stand and think from lack of food, and he quickly found that what he thought would be his defense — his trusted position at NATO — was now considered part of his “crimes.” “[The judge] said, ‘You are working for NATO, aren’t you?’ I said, ‘Yes I’m working at the headquarters on behalf of the Turkish Army, and I was appointed by the commander of the Turkish Army’,” Topkaya recalled. “But I couldn’t convince her [to release me]. Being pro-West and pro-NATO is a big crime in Turkey now.”

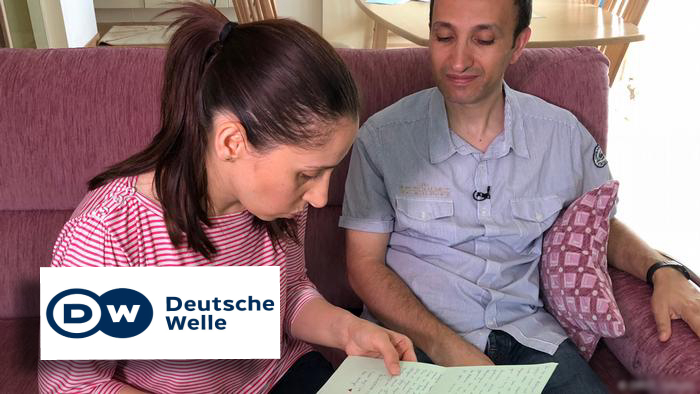

For more than 16 months Topkaya survived mentally on calls to relatives and letters from his wife and children. He displayed with obvious pleasure a drawing of Santa Claus from his eldest daughter that assured him he wouldn’t be on the “mischief list” that Christmas.

Eventually, he was told that trial preparation against him would take longer, which he attributes to the lack of evidence, so Topkaya was released into the custody of his parents, required to check in weekly with the police. But his lawyer warned him there were rumblings of a re-arrest just as Topkaya discovered an old civilian passport with a couple months more validity; authorities had missed confiscating it in house searches. Topkaya decided he would try to slip away.

He doesn’t want to explain his path precisely, to avoid putting obstacles in the way of future fugitives, but within a week, with some kindness and a lot of luck along the way, Topkaya was back at his apartment in Brussels. He reconnected with his loved ones while recuperating for several months, but he remained troubled about what he had witnessed, more than he worried about what might happen to himself. Despite the dangers, his family supported his decision to go public.

That’s when he finally did create a Twitter account detailing what happened to him and he believes is still happening to others. The Turkish version is causing quite a stir, he said, estimating that 90 percent of the reactions are positive and 10 percent extremely angry.

Turkish government-controlled newspapers brand him a “traitor” and concoct stories about him and other purged officers holding secret “treason meetings” in Germany. “I feel relieved with each tweet,” he smiled, “and I know the bad guys are afraid of it.”

Other purged NATO officers whom DW spoke to are full of admiration but also concerned for their friend’s safety. “He did something I do not dare which is amazing,” one said. “He came out of the shadows.” At the same time, he noted: “Erdogan’s long arm is everywhere. They try to find where we live, report on what we do, and if they get orders they carry them out. That’s why we keep away from the Turkish community here in Belgium.”

Topkaya said he has neither fear nor regret about his decision. He doesn’t feel he’s running from Erdoğan. Instead, he’d like to confront him and the other purge leaders. “I would like to face them. I would like to tell them that what they are doing is wrong,” he said. “What gives them courage is innocent people being frightened. We are innocent. We are on the right side. We should be more courageous.”