This is the first part of a series looking at Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s geopolitical ambitions, from his renewed push in Africa and the fringes of Europe to his troubled relationship with the EU.

In Baku’s Freedom Square last month, thousands of marching Azeri soldiers in fur hats and braided coats celebrated their country’s victory in the Caucasus — and the man who made it possible: Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Invited as guest of honour, the Turkish leader looked on as drones he supplied to Baku as it battled to regain lands lost to Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh were given a prominent place in the military parade. “Today is a day of victory and pride for all of us, for the whole Turkic world,” said Mr Erdogan, surrounded by Turkish and Azeri flags.

Mr Erdogan’s decision to throw his full weight behind Azerbaijan even as western powers called for a ceasefire after a fresh outbreak of fighting last autumn was the latest manifestation of his increasingly muscular foreign policy stance, characterised by uncompromising rhetoric and the ready use of hard power.

Over the past five years, Mr Erdogan has launched military incursions into Syria and northern Iraq, dispatched troops to Libya and engaged in naval stand-offs with Greece — interventions that have riled Turkey’s Nato allies, reignited old rivalries and generated new foes.

In recent weeks, as Mr Erdogan has come to terms with the US election defeat of his friend Donald Trump — and the need to lure back foreign capital to address Turkey’s mounting economic woes — he has said he would like to “turn a new page” with the west.

But it remains unclear whether Mr Erdogan is willing or able to compromise on the issues that plague Turkey’s relations with the EU, the US and Middle Eastern states — or whether the newfound conciliatory language will soon give way to renewed acrimony.

“There are small things [that Turkey has done] that could be considered an olive branch, but nothing substantial,” said a European diplomat. “If you look at the issues where we fundamentally disagree, both sides have the view that the ball is in the court of the other. So it’s very hard to go anywhere.”

The failed coup that changed Turkey

The 66-year-old Turkish president, whose party swept to power in 2002, has long sought to cast himself as a visionary who will — in the words of historian Soner Cagaptay— “make Turkey great again” both at home and abroad.

But a bloody attempted coup by rogue military factions in 2016 marked a rupture in Turkey’s dealings with the rest of the world, analysts say. It left Mr Erdogan even more suspicious of the west, pushed him closer to Russia’s Vladimir Putin, forced him to forge new political alliances at home and enabled him to take unprecedented control of the Turkish state.

In a speech three months after the attempted putsch, Mr Erdogan said the country would no longer wait for problems or adversaries to “knock on our door”. Turkey, he said, would instead “go and find them wherever they make their home and come down on them hard”.

Mr Erdogan at times plays to his religious conservative base by casting himself as leader of the Muslim world but also draws heavily on nationalist imagery and language. He likes to say that his nation is undergoing a sahlanis — a “rising” or “rearing up” — on the world stage.

Diplomats and analysts warn the strategy carries great risks, both for the economy and relations with regional and global powers. While 10 years ago, the guiding principle of Turkish foreign policy was “zero problems with neighbours”, Turkish analysts now joke that the new mantra is “zero neighbours without problems”.

Mr Erdogan’s foreign policy is described by his critics as “neo-Ottoman”, in reference to the empire that spanned southern Europe, western Asia and north Africa and preceded the modern republic. Turkish officials say their country is simply protecting its interests. “When France intervenes, it is just France — no one calls them Napoleonic,” one said.

The approach has come at a cost. “I don’t think Turkey has been this isolated in its history,” said Sinem Adar, a researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin. “There is an expanding front of countries that are confrontational toward Turkey.”

The purge, a president and a centralised state

The 2016 coup attempt, and the purge that followed it, allowed Mr Erdogan to take greater control of the armed forces. He also forged an electoral alliance with the ultra-nationalist party MHP, adopting its hawkish rightwing outlook on national security, especially Kurdish separatism.

“They have a similar idea, which is that Turkey must rise. It must increase its power,” said Evren Balta, a professor of international relations at Ozyegin University in Istanbul. “Both the AKP and MHP [also] share this basic idea that Turkey is under attack from inside and outside.”

At the same time, the transition in 2018 to a presidential system weakened the role of the country’s foreign ministry, traditionally the home of mandarins who saw Turkey’s natural orientation as towards the west.

Many are critical of what one former ambassador terms a reliance on “soldiers and spies” rather than diplomacy. On foreign trips, Mr Erdogan is rarely seen without intelligence chief Hakan Fidan and defence minister Hulusi Akar at his side.

The overseas adventurism has also had little pushback from political rivals. While the Republican People’s party (CHP) — established by Turkey’s founding father Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, whose motto was “peace at home, peace in the world” — has criticised “undiplomatic language”, the party has appeared reluctant to come out against policies that have proved popular with the public.

Mr Erdogan, who most analysts believe wants to remain in power for as long as possible, has used foreign policy for domestic political gain — going as far as to compare the German government to the Nazis and to advise the French president Emmanuel Macron to seek “mental treatment”. This attitude, however, has not gone down well in European capitals. One EU diplomat accused Turkey’s leader of acting like “a schoolyard bully”.

Terror, refugees and an international backlash

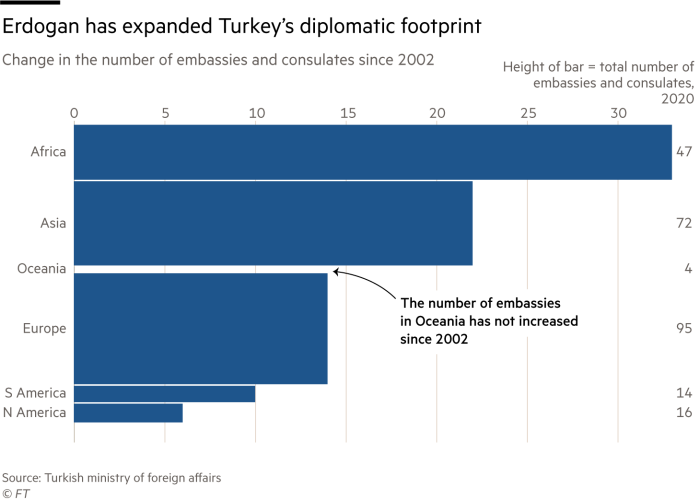

Mr Erdogan’s drive to make Turkey a regional power — reflected in a dramatic expansion of Turkey’s diplomatic ties with the Middle East, Africa and Latin America in the mid-2000s through trade and aid — quickly became fraught.

The country’s hopes of joining the EU faded amid mistrust and accusations of bad faith on both sides. A plan to build stronger ties with its Arab neighbours backfired as popular uprisings swept across the region. The Syrian war spilled into Turkey in the form of terror attacks and the arrival of millions of refugees. Turkish military operations in Syria and Libya — and its support for the Muslim Brotherhood — pitched Ankara against a powerful Arab alliance led by the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

Now Europe despairs at the decline in human rights in a country that is technically still a candidate to join the bloc. Washington is fuming at Mr Erdogan’s decision to buy an S-400 air defence system from Russia, which last month triggered long-awaited US sanctions.

Turkey’s relationship with newer partners is not straightforward either. His ties with Mr Putin are complex and often fraught, as made clear when 34 Turkish soldiers were killed in Syria last year in an attack that the US blamed on Moscow.

Still, Mr Erdogan has chalked up some successes. Turkish support turned the tide of the civil war in Libya. In Nagorno-Karabakh, Ankara’s backing of Azerbaijan has exposed the limits of Russian influence in the Caucasus.

Economic woes and softer rhetoric

The turbulent foreign policy has deterred much-needed foreign direct investment and, combined with concerns about Mr Erdogan’s management of the economy, been a source of pressure on the Turkish lira. The German carmaker Volkswagen suspended — and later cancelled — a plan to build a new factory after an international outcry at a Turkish assault on Syrian Kurdish forces in 2019.

Critics say that, for all the bombastic rhetoric, Turkey’s antagonistic foreign relations harm its interests. Sinan Ulgen, a former Turkish diplomat and chairman of Istanbul think-tank Edam, said: “The way I would judge the success of foreign policy is whether it helps Turkey to better protect its national interest and whether it helps Turkey to ensure more sustainable economic growth. On those criteria, it’s not a big success.”

The perilous state of the country’s $750bn economy — exacerbated by the coronavirus crisis — triggered a shake-up in November that resulted in the departure of Mr Erdogan’s son-in-law Berat Albayrak as finance minister.

Since then, and with the election of Joe Biden as US president, Mr Erdogan has made overtures to the west. In a video call with Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, on Saturday, Mr Erdogan said that “Turkey’s future is in Europe” and called for greater co-operation on issues including migration and trade.

The Turkish president has long been a pragmatist willing to make tough choices if necessary to sustain his hold on power. But some analysts suspect Mr Erdogan will be unwilling to make the compromises required to improve relations with Nato allies, in particular the US.

“I think that the goal of having an independent, strong foreign policy — whilst staying within Nato — will remain,” said Alan Makovsky, a former US state department official now at the Center for American Progress, a think-tank. “Maybe he’ll temper the rhetoric but I don’t think he’ll temper the vision.”

Additional reporting by Michael Peel, Simeon Kerr and Max Seddon

Source: FT