Iranian authorities have been intimidating and targeting Iranian asylum seekers in Turkey, who are becoming increasingly concerned about their safety, The New York Times reported.

A number of Iranian dissidents have been lured to Turkey only to be abducted and forcibly repatriated to Iran, while others have been extradited by Turkish authorities. One activist, Arsalan Rezaei, was stabbed to death in İstanbul in December after receiving several threats from agents of the Iranian government.

Another dissident, Masoud Molavi Vardanjani, was shot dead on an İstanbul street on November 14, 2019 a little over a year after his arrival. Vardanjani was a vocal critic of Iranian authorities and had posted a message on social media targeting Iran’s Revolutionary Guard three months before his death.

Two suspected gunmen and several other suspects, including both Turks and Iranians detained after the killing, told authorities they had acted on orders from two intelligence officers at the Iranian Consulate, according to two senior Turkish officials.

After Vardanjani’s death UN Watch, a UN-accredited NGO that monitors human rights violations, condemned the killing on Twitter, saying it was perpetrated by “assassins working for Iran’s consulate in Turkey.” They called on UN special rapporteur Agnes Callamard, who investigates extra-judicial killings, to ensure justice for Vardanjani.

Reuters confirmed: the murder of Iranian dissident Masoud Molavi Vardanjan on the streets of Istanbul was perpetrated by assassins working for Iran’s consulate in Turkey.

The world cannot be silent. We call on U.N. investigator @AgnesCallamard to ensure #JusticeForMassoud. https://t.co/n3aC7Hm68M

— UN Watch (@UNWatch) March 30, 2020

Fatemeh Khoshro, who describes herself as an animal rights activist living in Turkey, said she constantly received threatening messages on the phone, and her fiancé, Nicolas Aryan, was harassed by men who they believe were agents of Iran’s government.

Speaking to The New York Times, Khoshro said she had been imprisoned and beaten in Iran for taking part in street protests and upon release moved to Turkey. She took a short trip to Iran to visit her family and during the visit she was detained for 60 days, beaten and sexually assaulted. She claimed that during her detention, the interrogators showed her pictures of her with her fiancé in Turkey.

Her fiancé had worked in Iraq for the US Department of Defense in 2006, when the US military was fighting Iran-backed militias. According to Khoshro, he was “marked as an enemy” in the eyes of the Iranian government.

Khoshro claimed she was told to return to Turkey and join her fiancé, drug him and lead Iranian operatives to him so they could abduct him. She said that since arriving in Turkey she has refused to carry out the orders and has been constantly receiving text messages from her interrogator in Iran.

Khoshro said she was still very afraid although she was no longer in Iran. “There are some men who cover their faces and come into the building and bang on our door,” she said.

Iran has not only abducted dissidents from Turkey but has also been known to lure people to Turkey from Western countries in an attempt to forcefully repatriate them.

Habib Chaab, an Iranian opposition leader who lived in Sweden, was persuaded to fly to Turkey to meet a woman, who unbeknownst to him, worked for Iranian intelligence. Upon arrival, he was drugged and abducted in a van that went to Iran via Turkey’s eastern border.

Somayeh Ramoz, an activist who also spoke to The New York Times, said she was in hiding in Turkey because she received threats from Iranian intelligence agents. She added that she heard people speaking Farsi in front of her house one night who then attempted break in.

According to Michael Rubin, a scholar who specializes in Iran, Turkey and the broader Middle East, Turkey is one of the few countries where Iranians can travel without a visa. “This means that it is easy to infiltrate Iranian intelligence operatives and assassins to these [visa-free] countries,” he said.

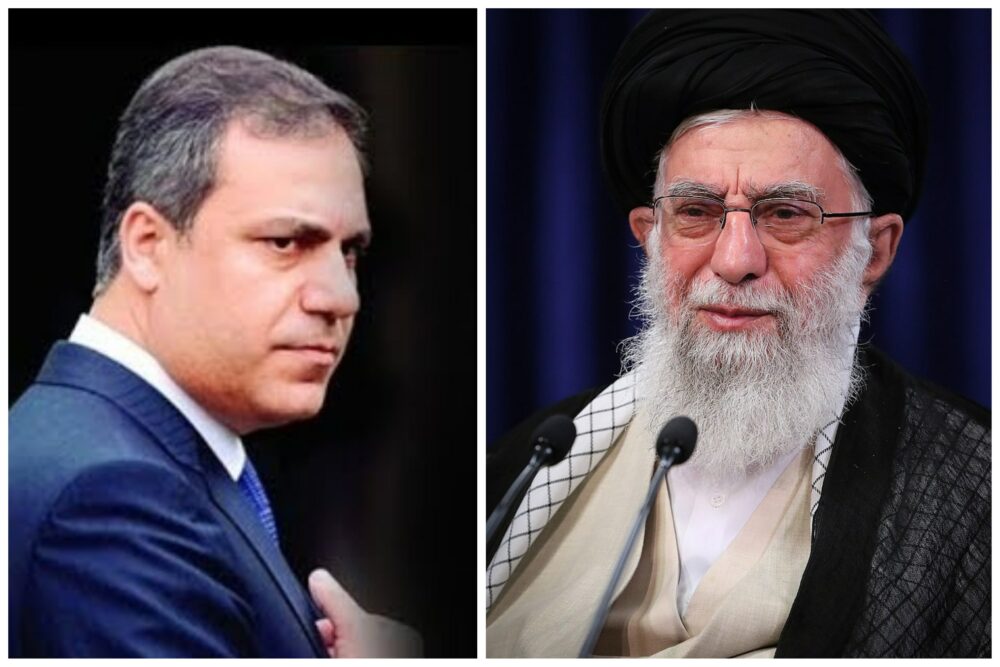

Rubin added that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has an amicable relationship with Iran, based on politics and not justice. He said that Erdoğan would turn a blind eye to injustice towards Iranians in Turkey if there were diplomatic favors concerned.

Indeed, Turkey and Iran have an extradition agreement, and Iranians who have crossed the border illegally or do not have residence permits have generally been deported.

Iranian nationals Saeed Tamjidi, 27, and Mohammad Rajabi, 25, who sought asylum in Turkey, were extradited in 2019 to Iran by the Turkish government despite the knowledge that they could face the death penalty. Their death sentence was upheld by an Iranian court in June 2020.

Peyman Aref, an Iranian journalist based in Brussels, talked to VOA and referred to previous extraditions. “Turkey and Iran have close intelligence cooperation. Turkey has handed over many Iranian activists to Iran in recent years,” he said.

Human rights organizations have condemned Turkey’s decision to extradite Iranian asylum seekers.

“Even if only one person is forcibly deported, it is a sufficient reason for others to feel unsafe here,” Tarık Beyhan, the campaigns and communications director for Amnesty International’s Turkey office, told VOA.

Based on United Nations data, more than 40,000 Iranians have sought asylum in Turkey since 2009. However, Turkey maintains a geographical limitation to the 1951 Refugee Convention and only applies it to individuals from Council of Europe member states.

In April 2013 Turkey adopted a comprehensive, EU-inspired Law on Foreigners and International Protection. According to this law, Turkey has obligations towards all persons in need of protection, regardless of country origin. Turkey registers non-Europeans as international protection applicants.

According to Turkish law professor İbrahim Kaboğlu, Turkey has an international obligation of non-refoulement to a country where a person faces the death penalty and/or torture.

Under international human rights law the principle of non-refoulement prohibits states from transferring or removing individuals from their jurisdiction or effective control when there are substantial grounds for believing that the person would be at risk of irreparable harm upon return, including persecution, torture, ill-treatment or other serious human rights violations. Under international human rights law, the prohibition of refoulement is explicitly included in the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) and the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED).

Source: SCF