Religion scholar Esra Ozyurek has a knack for identifying trends that ring warning bells about where Europe is heading.

She points to German Muslims, widely seen as deeply anti-Semitic, whose response to the Holocaust says much about the concerns about minorities in Europe.

Together with Julian Gopffarth, a student of the far-right, Ms. Ozyurek describes startling attitudes towards Muslims and Islam in Europe’s populist, nationalist and nativist far right that is widely perceived as anti-Muslim.

Rather than regurgitating denials of the Holocaust that have long been a popular trope in the Muslim world, Ms. Ozyurek notes that German Muslims acknowledge the genocide committed against the Jews and worry that they could suffer a similar fate. Muslim concern adds meaning to the post-World War Two notion of ‘Never Again.’

In doing so, Ms. Ozyurek implicitly highlights the failure of European social and economic integration policies that have left Muslim minority communities feeling vulnerable, marginalized, disenfranchised and fearful of their individual and communal safety and security.

It also spotlights the danger of reinforcing Muslim fears and isolation embedded in approaches that reduce societal concerns about the place of multi-ethnic and multi-religious Muslim communities in Europe to a security problem and put it on the defensive.

These approaches include French President Emmanuel Macron’s efforts to redefine Islam, Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orban’s concept of a Christian nation and efforts across the continent to counter political expressions and ultra-conservative strands of the faith.

The fundamental issues raised by Ms. Ozyurek’s observations come full circle in her separate charting, together with Mr. Gopffarth, of the convoluted relationship between Islam and far-right populist, nationalist and nativist movements.

The scholars demonstrate that the far right is no longer defined by its traditional denunciation of Islam as regressive, illiberal, and bent on conquering Europe.

Surprisingly, significant segments of the far-right have come to see Islam and practising Muslims, some of whom are high profile right-wing converts from Christianity, not as existential threats but as a bastion of resistance against modernity and enablers of a spiritual concept of European nationhood and identity.

These segments exist alongside continued traditional far-right demonization of Islam and Muslims.

Similarly, some Jews support Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party despite repeated anti-Semitic statements and questioning of Holocaust remembrance by various of the group’s leaders.

Jewish supporters of the far-right see its long-standing rejection of Islam as a barrier against anti-Israel and anti-Semitic sentiments in the Muslim community as well as increasing far-right attacks on Jews and Jewish symbols.

The attacks prompted Jews in France and elsewhere in Europe to wonder whether there still is a place for them on the continent. Some have packed their bags and emigrated to Israel.

Taken together, the scholars’ observations suggest that Europe is confronting an existential crisis. The appeal among Muslims of religious ultra-conservatism and political Islam, at times fused with nationalism like in the case of Turkey; existential Jewish fears; and the far-right’s quest for a reconfigured Europe are two sides of the same coin.

In other words, Europe, by looking at various social and political problems in isolation is missing the forest for all the trees.

Europe would be better off if it recognized that existential fear is what locks Muslims and other minorities and the far-right into a struggle that polarizes and debilitates societies.

Looking at the bigger picture could lead to conceptually revisiting long-standing social and economic policies that have created a crisis that threatens the pillars of Europe’s post-World War Two development and the existence of the European Union as we know it.

The opportunistic framing of issues like political Islam to serve the short-term interests of politicians, and catering to far-right anti-migration and anti-Muslim sentiment in a bid to counter its electoral appeal, pours salt into open wounds. It does little, if anything, to solve problems that only get worse if allowed to fester.

Mr. Macron’s crusade to create a French Islam is supported and inspired by countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, who see Islam-based politics as an existential threat to the survival of their autocratic rulers.

The crusade risks aggravating Europe’s existential crisis rather than forging a path towards a more integrated continent that is inclusive rather than exclusive.

So does Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz’s crackdown on expressions of political Islam that is void of measures to address legitimate concerns in the Muslim community and at best pays lip service to inclusion and combatting marginalization and discrimination.

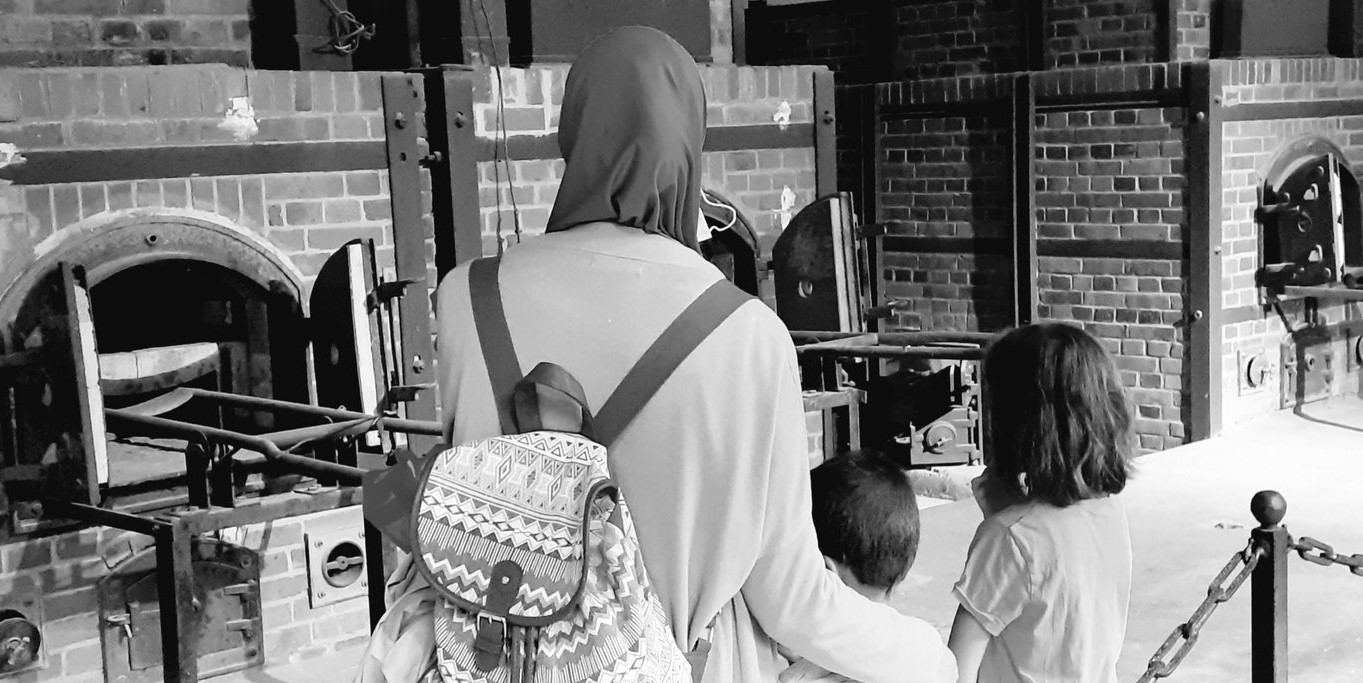

The extent of Europe’s crisis is evident in perceptions of German Muslim responses to the country’s effort to atone and remember the Holocaust by furthering a culture of solidarity and collective memory.

Rather than acknowledging that German Muslim fears of becoming victims of a 21st-century targeting of a religious group constitute recognition and engagement with the Holocaust, Holocaust educators dismiss Muslim responses as “wrong” and “unsuitable.”

“When they go to visit the camps, immigrants start to feel like they will be sent there next. They come out of the camp anxious and afraid. I do not like it at all when they do that, and (so) I do not even want to take them there.” Ms. Ozyurek quoted Juliana, a concentration camp guide, as saying.

What Ms. Juliana was really saying was that she found it difficult, if not impossible, to acknowledge that German minorities fear that the Holocaust could be repeated.

Her inability to relate to Muslim fears, whether realistic or not, signifies a refusal that is reflected in policies to recognize that engagement with existential concerns of a minority is part and parcel of drawing lessons from the Holocaust and core to ensuring that such crimes do not happen again.

By the same token, the far-right’s embrace of recent converts to Islam speaks to much more than the epiphany of those who found solace in a faith they long demonized.

Recent converts include Joram van Klaveren, a former member of rabid Dutch anti-Muslim crusader Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom, and Arthur Wagner, a leading member of the AfD.

AfD campaigned in Germany’s 2018 parliamentary election under the slogans “Islam has no place in Germany” and “Against the Islamization of Germany.”

The far right’s embrace of Messrs. Van Klaveren and Wagner contrasts starkly with the expulsion from Mr. Wilders’ party in 2013 of Arnoud Van Doorn once his conversion to Islam became public knowledge.

Mr. Van Doorn’s Unity Party this week forced a baker who was on the group’s slate for next month’s parliamentary elections to leave not because she was Jewish but because her cakes were pornographic. Jolisa Brouwer figured prominently on the party’s list to counter allegations that it was anti-Semitic and supported Islamic militancy.

“Competing visions of ‘Islam as threat’ and ‘Islam as renewal’ continue to feed into the rival visions of German national identity as an embodiment of modernity on the one hand and as a spiritual alternative to western modernity on the other,” Ms. Ozyurek and Mr. Gopffarth argue.

The embrace of Muslims and Islam as allies in an effort to give meaning to modernity perceived as predominantly materialistic by significant segments of populism, extreme nationalism and nativism enables the far right to broaden its appeal and project itself as non-racist.

It also suggests, like in the case of German Muslims, a far broader societal struggle that seeks to forge new communal and national identities as well as a rejuvenated European identity.

There is good reason to distrust changing attitudes towards Islam among some on the far right.

Ms. Ozyurek and Mr. Gopffarth note that the Nazis idealized Islam as a manly, orderly, and belligerent religion that could bolster the fight against what they viewed as a decadent liberal Americanization and Jewish world government.

The story of German Muslims and far-right engagement with Islam, nonetheless, offers an opportunity at a time of historic inflexion as a result of the pandemic and the concomitant economic downturn to tackle societal fault lines.

If left unaddressed, these fault lines are likely to fuel polarization; further legitimize prejudice and racism; and undermine the social cohesion needed to tackle existential problems not only in Europe but across the globe.

By: Dr. James M. Dorsey – an award-winning journalist and a senior fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore and the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute.