American historian and political commentator Ruth Ben-Ghiat said in an interview with the Stockholm Center for Freedom that any society can be susceptible to an authoritarian strongman figure if it’s the right time. “It’s very important to see the warning signs in the beginning and stop these people in their tracks,” she warned.

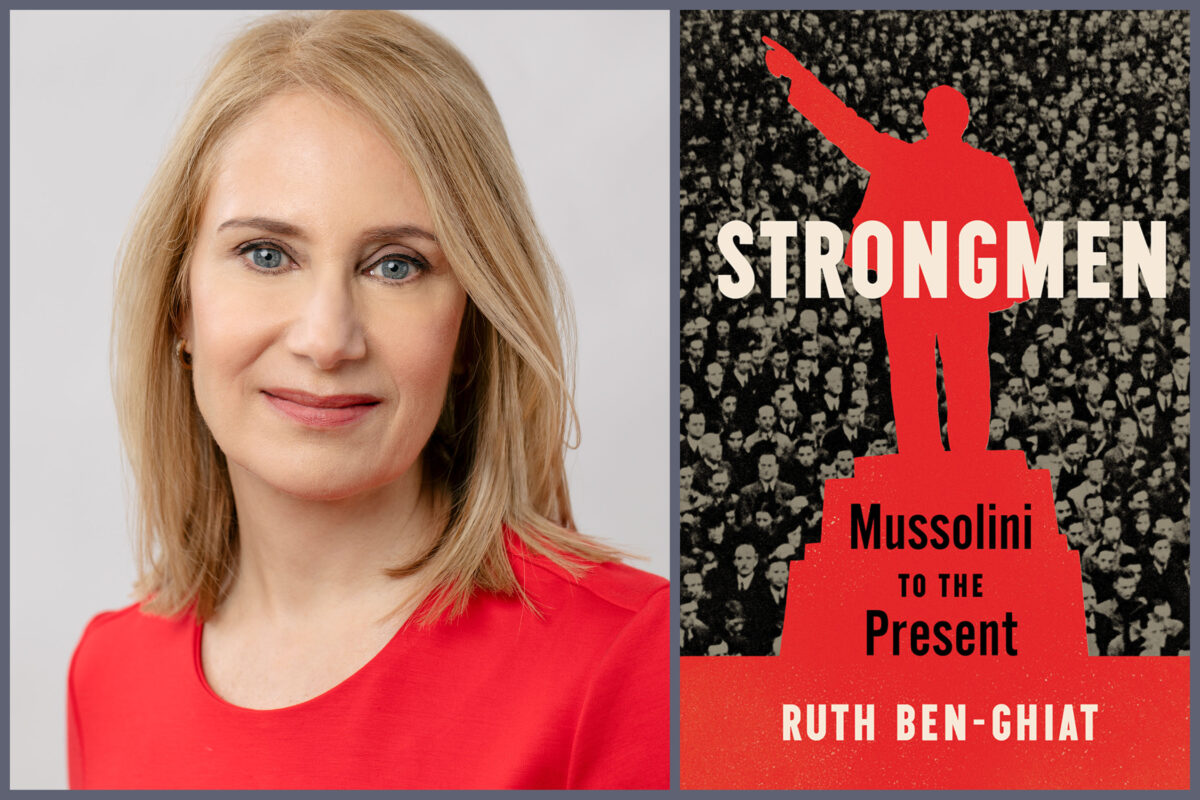

As part of SCF’s interview series “Freedom Talks,” our research director Dr. Merve R. Kayıkçı talked to Ben-Ghiat about her latest book, “Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present,” the rising authoritarianism around the world, the link between masculinity and authoritarianism and how to stop the “strongmen.”

Ben-Ghiat is a professor of history and Italian studies at New York University and a commentator on fascism, authoritarian leaders and propaganda and the threats they pose to democracies. As the author or editor of six books, with more than 100 op-eds and essays for CNN, The New Yorker and The Washington Post, she brings a historical perspective to her analyses of current events. Her insight into the authoritarian playbook has made her an expert source for television, radio, podcasts and online events around the globe.

She also publishes Lucid, a newsletter about abuses of power and how to counter them.

In the book you begin by describing how there is a strong link between masculinity and authoritarianism. What are some aspects of masculinity that make an authoritarian leader and draw the support of people?

There are many types of masculinity in the world, but the strongman is an authoritarian leader who not only damages or destroys democracy but uses this kind of toxic, arrogant masculinity as a tool of rule. So some of them, like Mussolini and Putin, will use their bodies, they strip their shirts off, and so they let their bodies become kind of emblems of national strength. And they also use threats. Their strength is also threatening. This is a kind of masculinity that’s about domination, possession of others, and it connects to a worldview where these leaders have a proprietary conception of power and the state so that they seize businesses, as Erdoğan does in Turkey and Putin in Russia. So this is a kind of masculinity, and the reason I use arrogance is that there is nothing that shouldn’t be theirs.

Do you think in some societies people are more drawn to a father figure, a savior, than in other societies?

One of the ways these leaders find popular appeal is that they correspond to ancient archetypes of male figures, such as the protector or the father figure and also the savior. One common theme is that they all say they are going to save the nation. Only they have unique qualities, and this is where their charisma can come in or their personality cult. Only they can save the nation. On the one hand, they project themselves forward in time, where they say, “I’m going to make things great in the future.” They often pose as modernizers where they’re building highways and airports. But they also channel nostalgia, where they say, so it’s not “Make the nation great again,” as Donald Trump would say, it’s not “Make the nation great,” it’s “Make it great again.” So the nostalgia for a world that used to be better, for a lost empire, is very important. Mussolini had the Roman Empire, Erdoğan has his fantasy of reviving the Ottoman Empire. … They attract people by playing into fantasies of grandeur and power.

One of the things my research taught me is that any society can be susceptible to this strongman figure if it’s the right time. The right time is sometimes after a defeat … or a time where there has been a lot of social change that includes gender emancipation or racial equity, and white males in the European and American context often feel threatened.

In the book you mention that most strongmen have anger issues. Could you elaborate on that?

Historically people have seen authoritarians as crazy, starting with Hitler. People said he was a ranting fool and crazy. I was astounded doing my research at how similar the personalities of authoritarian leaders were. They each have their own quirks and not exactly the same, but they all have paranoia, narcissism, they all are very aggressive, and they like to humiliate others. This leads to certain styles of governance that are very dysfunctional and full of turmoil. So they create inner sanctums around themselves with family members — like Erdoğan — because they’re corrupt and need people to keep their secrets. But everybody else is humiliated and fired and re-hired. So their governments are not stable at all. Their personalities are impulsive and they think they are God sometimes and that they’re infallible. They make snap decisions which are not good for policy making. Ultimately, their governments are very destructive and unstable, even though the myth of authoritarians is that these are take-charge men who will bring peace and stability.

Their personalities are full of turmoil, but dismissing them as crazy is shortsighted because they’re opportunists who are extremely skilled at managing people. They know how to connect with people. Erdoğan cries a lot and shows a lot of emotion. Not only are they highly aggressive, they have got this politics of emotion that makes people feel included. So all of this does not add up to somebody who’s crazy. It adds up to somebody who’s very skilled and very savvy, actually.

When the political situation in Turkey turned for the worse, one of the first groups to be targeted were academics who were critical of the government. What is the fixation with academia and academics for authoritarians and populists?

Authoritarian states need intellectual legitimacy because they are thug states, mafia states. Violence is their everyday behavior. On the one hand they need intellectuals to write their propaganda, to be their spokespeople, to do nationalist research. They need intellectuals to rewrite the schoolbooks to support their nationalist historiography. On the other hand strongmen disappear people, but they also disappear fields of knowledge that conflict with their goals. While they promote certain things, they also ban other things and threaten people to not work on those topics.

In Hungary Orbán banned gender studies overnight. That was a prelude to his anti-trans policies. So sometimes universities are the first place where the recasting of knowledge and propaganda shows itself. … In authoritarian regimes academics become political people, the government sees them as political people, and then sometimes they become enemies of the state. Erdoğan has jailed and detained so many academics, and he is threatened by certain kinds of research.

At a broader level, authoritarians are always threatened by fact-based knowledge. The facts are their enemy. Propaganda means that you have to create an alternate reality that your believers will follow, and research based on science and scientific method becomes the enemy.

What about international support? Did the EU support the stability of Erdoğan’s regime for the sake of the migration deal?

Erdoğan is a good example of benefitting, that the EU has not been standing up for democracy. They shouldn’t be funding Erdoğan, who has locked so many people up and is so corrupt. So what is the EU standing up for? There are groups of foreign enablers because authoritarians, in all areas of their policies, depend on foreign capital and goodwill. Erdoğan is just the latest who is doing all these infrastructure improvements with foreign money and foreign debt. If financial institutions were guided more by morality, they could easily retract these foreign lending practices and make them dependent on democratic actions.

Erdoğan is a good example of benefitting, that the EU has not been standing up for democracy. They shouldn’t be funding Erdoğan, who has locked so many people up and is so corrupt. So what is the EU standing up for? There are groups of foreign enablers because authoritarians, in all areas of their policies, depend on foreign capital and goodwill. Erdoğan is just the latest who is doing all these infrastructure improvements with foreign money and foreign debt. If financial institutions were guided more by morality, they could easily retract these foreign lending practices and make them dependent on democratic actions.

These are leaders who care only about money and power, so the West not only does not use its power to change the behavior of autocrats, they help them. The same could be said for international financial institutions and law firms that help autocrats store their money in offshore tax havens.

The anti-globalism of authoritarians is fake because they are the biggest globalists of all. They are dependent on international infrastructure coming from democracies and also foreign autocracies to keep in power. A few years ago Erdoğan had five different American PR firms working for him to support his interests in Washington. He and Trump were quite close.

What do you think Western democracies could have done differently to prevent what is happening in Turkey today?

It is very important to see the warning signs at the beginning and stop these people in their tracks at the start and let them know that the EU is not going to fund them anymore or make treaties for migration, and really flex the muscle of democracy and open society and use that. These are men who see any weakness or gentility towards themselves as weakness. They’re always testing the boundaries. … Violations of international law are a test, so the first time there’s a violation, we need to strike very hard. All of these guys in power now have been there for a long time, so it’s too late to retrain them, but we don’t do what we could do. These men only listen to force, and if the EU and democracies don’t show that, then we’re not going to get results.

Can we say that authoritarianism is in part the result of democracy failing to fulfil its promises?

To some extent, absolutely. Authoritarians have managed to make people feel included and give them a sense of community. They have been better at that with rallies and chants which may seem superficial but are part of a political culture. Liberal democracy has never been as skilled at that. Authoritarian leaders are able to make an emotional connection. Liberal democracy has been about reason and not raw emotion. This goes back to the figure of the leader who cries in public like Erdoğan and who has this charisma that’s constructed. Once they’re in power, there are huge resources devoted to their personality cults. But people connect with them, and one of the reasons I want to concentrate on leaders is because they are so important for the success of these dynamics. For example, on the personality cult it’s fascinating that the rules of personality cults actually haven’t changed for a hundred years, even though today we have social media and back then there were news reels. So the leader needs to be an everyman who can connect with anyone. At the same time they have to be superman, they have to be men above all other men. They need to be someone who’s all powerful and can get away with things. They like to believe they have divine guidance. It’s the same all over the world and says something about human psychology that we seem to need this in our leaders.

In recent years gender-based violence has increased and even become more visible in Turkey. Would it be right to assume that there is a correlation between rising authoritarianism and the vulnerability of women?

Women have been the targets of authoritarians as much as lawyers, judges, journalists and the critical opposition. They have traditionally been an enemy, even in situations where the state ideology preaches equality, like in communism, you know, Joseph Stalin took away abortion rights. Most authoritarians have ambitions to re-found the family. And this is where the father figure comes in. Authoritarians fear demographic change, so women become pawns and tools of larger social demographic political schemes. If authoritarians are expansionists like the former fascists, then women have to produce babies. Women’s bodies and rights become legislated.

When you have a leader who models through his person disrespect for women or even hatred for women and a kind of violent aggressive personality, then this is reflected throughout society, and it’s often backed up with policies. It’s a little-known fact that Trump, who is a serial sexual assaulter who became president, partly decriminalized domestic violence in the US in 2018. Physical violence was still domestic violence, but all other kinds of abuse — emotional, psychological — were no longer considered domestic violence so women couldn’t get help from the authorities. This leaves them more vulnerable.

Gaddafi was a real revolutionary in the beginning and believed in women’s rights. He hugely bettered the legal status and the employment status of women in Libyan society. Women had the right to work and own their own property. But he fostered a culture of sexual assault and violence as his hold over the country strengthened.

Do you think it is possible to recover from an authoritarian period? After countries are ruled by authoritarianism, is it possible for them to return to liberal democracy, or will they always have some sort of political instability?

If you don’t hold people accountable and you don’t have a mechanism for testimonials to come out for people, like in the former East Germany, when they made public the Stasi files and people could go and see their own file on themselves. This was very empowering to people and created for many decades a lot of stability in Germany. But Germany versus Italy is an interesting case because Italy did not go through an aggressive de-fascism. So the fascists went underground, but it was not rooted out. It was not made to be as taboo in the culture as in Germany. After Franco in Spain you were not allowed to talk about it, so there was democracy but no accountability. There’s always a lot of fear around revenge, retribution, vendetta, and so sometimes in transitional eras sometimes even the people who are on the side of the victims can be afraid to let the energies of the victimized find the full expression. Accountability is key.

If you don’t hold people accountable and you don’t have a mechanism for testimonials to come out for people, like in the former East Germany, when they made public the Stasi files and people could go and see their own file on themselves. This was very empowering to people and created for many decades a lot of stability in Germany. But Germany versus Italy is an interesting case because Italy did not go through an aggressive de-fascism. So the fascists went underground, but it was not rooted out. It was not made to be as taboo in the culture as in Germany. After Franco in Spain you were not allowed to talk about it, so there was democracy but no accountability. There’s always a lot of fear around revenge, retribution, vendetta, and so sometimes in transitional eras sometimes even the people who are on the side of the victims can be afraid to let the energies of the victimized find the full expression. Accountability is key.

What do you think of the use of the “us” and “them” dichotomy? Such as the use of anti-Semitic, anti-migrant and anti-West narratives.

Authoritarians create a community of the included through excluding others. All the community building rituals like rallies, are built on the active exclusion of some so that others feel included. There can be various enemies who are demonized. Sometimes these are Jews, other times these are illegal immigrants, or George Soros, who kind of is everything. He’s a very convenient symbol of many things. But this is the essential dynamic that appeals to very primitive and powerful feelings in people, to feel one with a community and to feel superior. Nazism and fascism because it was so racially oriented made a woman who was deemed an Aryan superior to a man who was not Aryan. So when people ask why women so often support these leaders, it’s because they have status if they are in the included community over men. In the US, for example, a white woman who loves Trump felt superior to a non-white man. So it plays with gender hierarchies and is a very powerful thing. The most successful of these rulers are the ones who know how to play on that “we.” And they make themselves personally the embodiment of the nation of that “we.” Often they say, if you attack me, you’re attacking the whole nation. In Erdoğan’s case, anyone who is against his government is a terrorist. Erdoğan is a typical authoritarian personality with all of his insult suits. That is very interesting to me as a clue to this very insecure and prideful personality who gets pleasure out of humiliating and ruining others. 21st century authoritarians use the law and lawsuits to financially and psychologically exhaust people. They make it too tiring so you can’t survive and you’re harassed. So you self-censor, and that’s their ultimate goal.

In Turkey people like to say geography is one’s fate. Is authoritarianism a “fate” for some countries?

I find this fatalistic. Authoritarians want people to be so resigned and hopeless and feeling that it’s their destiny to be in political situations without agency and rights that they give up. … In fact the suffering of the past can make people much more determined to have freedom. The opposite being a place like the United States, which has never had a national dictatorship or foreign occupation, and so people did not see the warning signs of what Trump represented. … They don’t have the history at all and can be complacent, and this is also a problem.

What can we do to safeguard our democracies? Especially, people who are still living in free democratic countries, what can they do for its continuity and also to protect those in vulnerable and dangerous situations?

I think going back to pressuring the EU, pressuring financial and legal institutions and all the enablers of authoritarianism. We don’t have enough journalism articles devoted to them. They need to be shamed and outed, and that is one thing that would have a practical effect, making these authoritarians pariahs, so that US law firms and PR firms won’t take their cases on, so that Erdoğan won’t have five different companies to convey his propaganda to US politicians.

The kind of work your center does in defense of human rights is important because a lot of that means publicizing the stories of the victims. This is why I included a lot of unpleasant material in the book because today we have the far-right all over the world who openly say, for example, “Pinochet did nothing wrong.” This erases the history of what he did do, so that’s why although it’s not nice to write about the torture, it’s very important. So in real time when Erdoğan is beating up people and they come out of prison and they have the marks of what they have suffered, it’s important to show that because this is the kind of evidence they try to cover up.

Source: Stockholm Center for Freedom (SCF)