Oktay İnce, a documentary filmmaker and activist, appeared in court on Tuesday for the first hearing in his trial for insulting Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan after his archives concerning street protests were seized by the police in a home raid in 2018, the Bianet news website reported.

İnce’s archive documented 20 years of street protests by people demanding better rights. He posted parts of his archive on Twitter under the handle “Seyri Sokak.” İnce was charged with spreading terrorist propaganda, and on October 18, 2018 the police confiscated his laptop, other electronic devices and his archives.

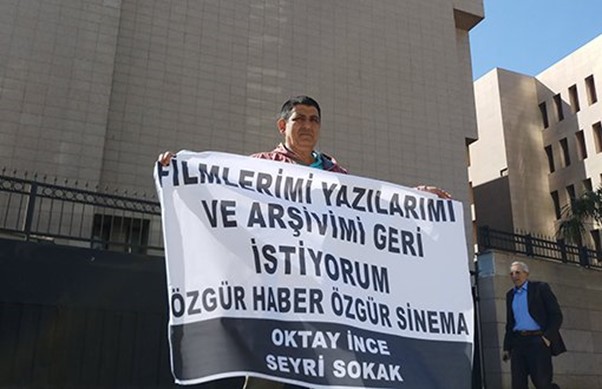

Following the seizure of his property, İnce staged a protest demanding the return of his archives, after which insult charges were brought against him. Posts from an anonymous Twitter account whose content was not disclosed were also presented as evidence against him. İnce’s next hearing is scheduled for November 23.

Insulting the president is a crime in Turkey, according to the controversial Article 299 of the Turkish Penal Code (TCK). Whoever insults the president can face up to four years in prison, a sentence that can be increased if the crime was committed through the mass media.

According to the Justice Ministry, a total of 160,169 investigations and 35,507 cases have been launched on charges of insulting the president over the past seven years, beginning with the election of Erdoğan to the presidency in 2014 to the end of 2020.

The European Court of Human Rights on Tuesday urged Turkey to amend the law granting Erdoğan extra protection from perceived insults while it awarded damages to a man jailed over Facebook posts deemed disrespectful of the president.

The court found that the conviction had a “chilling effect” that discouraged criticism and constituted a violation of the man’s freedom of expression.

It also said the Turkish law imposing harsher punishments for anyone convicted of insulting the president was “against the spirit” of the European Convention on Human Rights, which Ankara ratified in 1954.

“A state’s interest in protecting the reputation of its head of state could not serve as justification for affording the head of state privileged status or special protection vis-a-vis the right to convey information and opinions concerning him,” it said.

Source: Stockholm Center for Freedom (SCF)