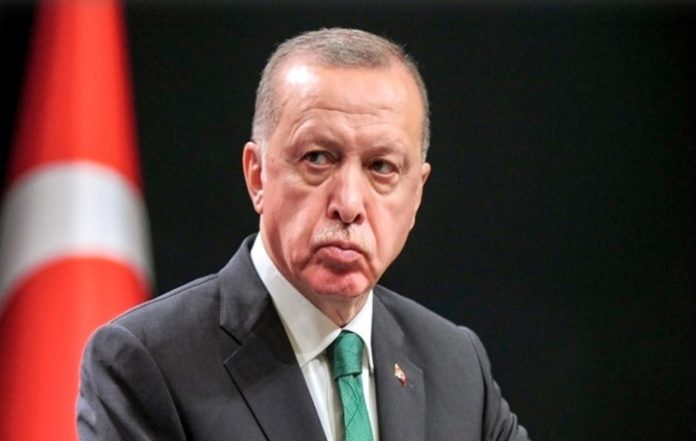

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan last week said he instructed Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu to declare the ambassadors of 10 countries — the US, Canada, Germany, France, Denmark, Norway, Netherlands, Sweden, Finland and New Zealand — to be personae non gratae. The reason for this was a joint statement made by these ambassadors on Oct. 18 inviting Turkey to release Osman Kavala, a well-known philanthropist and businessman.

No ambassador would take such an initiative without the instruction of his country’s authorities. Therefore, there must have been coordination among the various capitals before agreeing to such a joint action. Since there are absentees among the EU, NATO and Western bloc countries, we may presume that some capitals disagreed with this initiative and chose not to antagonize Turkey unnecessarily.

Both the content and the method of the ambassadors’ initiative were at odds with established practice. A resident ambassador is not expected to interfere in the internal affairs or the judiciary procedures of their receiving country. Firstly, according to widespread practice, a diplomatic demarche is only carried out in the receiving country if it is a positive message for the host. If it is a negative message, the demarche must be carried out in the capital of the sending state. The foreign ministry invites the foreign ambassador to the ministry or releases a statement. This prevents its ambassador from being rebuffed in the receiving state. So these 10 countries chose the wrong capital to issue such a statement.

Secondly, even if the ambassadors were instructed to make such a statement, diplomatic niceties require that they should do it individually by paying a visit to the foreign ministry of the host country and expressing politely the feelings of the sending country on the subject matter in question. A common action will annoy — and possibly hurt — the host country. This is exactly what happened in Ankara with the statement of these 10 foreign ambassadors.

Having said all this, Erdogan’s reaction was not proportionate with the initiative of these ambassadors. He probably did not figure out that declaring an ambassador undesirable is the last step before declaring war on a country. To declare as undesirable the ambassadors of 10 countries — including a superpower like the US, many NATO allies and a big trading partner like Germany — is probably going to remain as a unique case in the annals of diplomatic relations.

To overcome the crisis, the Turkish Foreign Ministry and the US State Department agreed last week to issue a statement saying Washington “maintains compliance with” Article 41 of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. The State Department made the promised statement on Oct. 25, but this was nothing more than a confirmation of facts, as it said that the US will continue to remain compliant with the convention, as it has been in the past.

Erdogan’s conciliatory tone suggests he now understands the various implications if these ambassadors were to be declared personae non gratae

Yasar Yakis

The Turkish version of the text stated — with a grammatically incorrect phrase — that the US “confirms compliance” with Article 41. Even if the two texts do not tally, this constructive ambiguity saved the day.

“Our goal is never to create crises,” Erdogan said after a Cabinet meeting one day after the US statement. “It is to protect the rights, laws, honor and sovereignty of our country.”

Probably realizing the damaging consequences, he felt compelled to consider this attitude of the State Department as the US taking a step back. His conciliatory tone suggests he now understands the various implications if these ambassadors were to be declared personae non gratae.

Furthermore, Erdogan was also preparing for the weekend’s G20 meeting in Rome and the UN climate summit in Glasgow. He had a long catalogue of issues to sort out with US President Joe Biden and maybe refrained from casting a shadow over these important meetings.

The pro-government Turkish media celebrated the outcome as Erdogan standing strong.

What is lost in this stormy atmosphere is Kavala’s fate. He was acquitted by the Turkish courts after being accused of organizing and financing the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul in 2013, but he has remained in custody for more than four years. The European Court of Human Rights last year ordered Turkey to release him immediately. The Turkish government has not so far said that it will not implement the ECHR verdict, but Kavala is being kept in custody because of an indictment that has been under preparation for more than a year.

The gist of the ambassadors’ demarche was to secure Kavala’s release. Turkey has not only recognized the ECHR’s jurisdiction, but it has also passed a separate law that provides that, in cases where an international convention contains a provision that contradicts Turkish legislation, the provisions of the international convention will have primacy.

At the end of the day, 10 countries have spelt out what they had in mind and it does not look as if they have stepped back, while Turkey remains defiant and Kavala continues to serve a sentence without ever being convicted.

By:

*Yasar Yakis – a former foreign minister of Turkey and founding member of the ruling AK Party. Twitter: @yakis_yasar

Source: Arab News

***Show us some LOVE by sharing it!***