When Alexander Lukashenko visited a group of migrants stranded on Belarus’s border with Poland after their attempts to cross illegally were blocked by Polish forces, he urged them to keep trying.

“If you want to go west, we won’t choke you, grab and beat you. It is your choice. Go across!” Belarus’s autocratic leader told the group, who had gathered outside a warehouse near Bruzgi — their temporary shelter as eastern Europe’s icy winter sets in.

“Go! That’s the whole philosophy. I know that what I said will not please everyone, especially abroad, but it is true, they should know the truth,” Lukashenko said in a visit on November 26 that was filmed and televised.

Lukashenko’s very public orchestration of a humanitarian crisis — European officials have accused his regime of simplifying entry for Middle Eastern migrants into Belarus and then directing them towards the border — is perhaps the most blatant recent example of coercive diplomacy using displaced people as a weapon.

Increasingly, that weapon is being aimed at the EU as a way of exploiting its deep political divisions and public fears over uncontrolled immigration. The phenomenon is driving a further hardening of attitudes within the union towards migration and asylum seekers, as member states seek new ways of strengthening their borders and deterring displaced people from heading to the EU. The goal, according to Marcin Przydacz, Poland’s deputy foreign minister, is “to check the resilience of our countries” by “shaking the emotions of public opinion”.

Weaponised migration: Crackdown in East Pakistan (1971)

Displaced: 10m

What happened: A crackdown by the Pakistani military over a burgeoning independence movement in what was then East Pakistan resulted in genocide. Ten million Bengali refugees fled to India, putting pressure on New Delhi to intervene.

What happened next: On December 5, Indira Gandhi recognised Bangladesh’s independence and on December 16 Dhaka fell to the Indian forces. By spring the next year, 9m people were repatriated.

Governments are grappling for ways to respond to weaponised migration alongside other coercive tools aimed at social and political destabilisation, such as cyber attacks and disinformation, which have been refined into a sophisticated military doctrine of “hybrid war” by Moscow and copied by others.

“The classic distinction between war and peace has been diminishing,” Josep Borrell, the EU’s foreign policy chief, said last month as he unveiled the EU’s new “strategic compass” or foreign policy strategy. “It is not black and while. The world is full of hybrid situations where we face intermediate dynamics of competition, intimidation and coercion. And what we are seeing today at the border of Poland and Belarus is a typical example of that.”

Europe is hardly the only region where immigration is a sensitive issue. But the EU has a unique set of features that its adversaries such as Lukashenko can exploit.

National governments are primarily responsible for external border control but there is borderless travel inside much of the bloc, no system for managing internal flows and no functioning mechanism for sharing responsibility for asylum seekers.

Some member states are much more exposed than others, either as entry points or as preferred destinations. And there are divisions among countries and, moreover, within them, that make the issue politically radioactive for leaders.

“Belarus picked on something it identified as our fragility,” says Natalie Tocci, director of the Institute for International Affairs in Rome and a visiting professor at Harvard. “It was absolutely right.”

Margaritis Schinas, European Commission vice-president, argues the Belarus episode marked a shift in the political weather across the union by highlighting the extent to which the entire bloc is exposed to migration issues. This, he argues, may foster a greater sense of solidarity.

There were previously doubts in parts of the union as to whether migration was really a common problem, he said. “Now the attack by Belarus has galvanised European public opinion and contributed significantly to a convergence of views that we will never be able to cope externally unless we can cope internally.”

Stage-managed ‘invasions’

Use of migrant flows as a tool of aggression or intimidation is neither new nor rare. Kelly Greenhill, a US academic and author of the book Weapons of Mass Migration, has documented at least 76 instances since the 1950s and concedes there are probably many more.

Some are vast in scale. A crackdown by the Pakistani military in 1971 sent 10m Bengali refugees into India in part to pressure New Delhi into ceasing its support for the Bengali rebel movement. Fidel Castro permitted and then encouraged 125,000 Cubans to flee to the US in the Mariel boatlift of 1980, partly to extract political concessions from US president Jimmy Carter, who had initially welcomed the influx before it turned into a tide.

Some coercers have been explicit about their motives. Attempting to play on racial tensions within Europe, Libyan leader Muammer Gaddafi in 2010 demanded €5bn a year to stop illegal African migration. “Tomorrow Europe might no longer be European, and even black, as there are millions who want to come in,” he said.

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan has repeatedly threatened to flood the EU with some of the 4m refugees living in his country. Last year officials bussed thousands of them to Turkey’s land border with Greece, leading to tense clashes with Greek border guards.

Erdogan complained that Turkey was overburdened and that the EU was not doing its part. Turkey struck a deal with the EU in 2016 to staunch the flow of mostly Syrian refugees into Europe in return for €6bn in aid and an EU promise, so far largely unfulfilled, to admit more recognised asylum-seekers.

“After we opened the doors, there were multiple calls saying ‘close the doors’,” Erdogan said at the time. “I told them, ‘it’s done. It’s finished. The doors are now open. Now, you [Europe] will have to take your share of the burden’.”

Other states have used the same intimidatory techniques with far narrower objectives. In May, Moroccan authorities encouraged thousands of migrants, including many of its own citizens, to swim round a border fence and enter the Spanish North African territory of Ceuta. Some were duped into thinking that the footballer Cristiano Ronaldo was playing a match in the enclave.

The stage-managed invasion was an act of protest and of pressure. Rabat was furious that Spain had allowed in Brahim Ghali for emergency medical treatment. Ghali is a leader of the independence movement for Western Sahara, over which Morocco claims sovereignty.

For months Rabat had been pushing Madrid to follow the Trump administration’s recognition of Morocco’s sovereignty claim. It had allowed the number of migrants arriving from its waters to Spain’s Canary Islands to rocket, says a Spanish official: “They couldn’t force Spain to change its mind, so they used this very hybrid form of war to pressure the country.”

Madrid refused to bow to Moroccan pressure although Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez subsequently replaced his foreign minister.

Weaponised migration: Mariel boatlift (1980)

Displaced: 125,000

What happened: In April 1980, Fidel Castro announced that all Cubans wishing to emigrate to the US could board boats at the port of Mariel. Some 125,000 Cubans in 1,700 boats fled to US shores, overwhelming the coast guard and putting political pressure on then president Jimmy Carter.

What happened next: More than 1,700 “Marielitos” were imprisoned and deported, while hundreds more were detained until they could find sponsors. An agreement between the US and Cuban governments in October 1980 ended the exodus.

To the north, the short 13km span of the Strait of Gibraltar between Africa and Spain stands as a symbol of Europe’s vulnerability to weaponised migration. Geography leaves Europe exposed to turmoil in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, as well as to the effects of huge discrepancies of wealth and opportunity between relatively short distances.

“What makes Europe susceptible is that we are surrounded by neighbours who are in trouble,” says the Spanish official. “And the neighbours of our neighbours are in even greater trouble.”

European disunion

Geography is only one reason for the EU’s susceptibility. Its adversaries are using the EU’s political foundations against it, says Mark Leonard, director of the European Council on Foreign Relations and author of The Age of Unpeace, a book about how interdependence between countries creates conflict.

The EU was built on multilateralism and free and open markets and then it tried to extend the model to the rest of the world through global institutions and trade agreements.

“For Europeans this was a kind of ideology as well as an opportunity,” Leonard says. “We found ourselves much more bound into the world so we are much more vulnerable.”

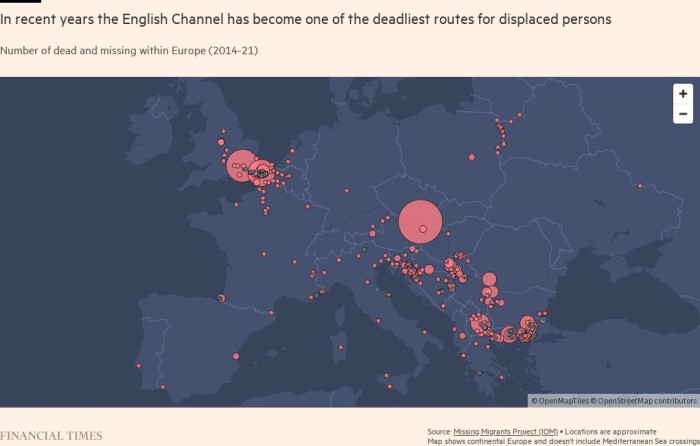

Those who seek to weaponise migration meanwhile understand that the EU is still grappling with the destabilising effects of the 2015-16 crisis, when around 1.5m asylum seekers and refugees poured into Europe.

Weaponised migration: Libya and the EU (2010)

Displaced: unknown

What happened: In 2008 more than 32,000 people were caught trying to enter Italy illegally. The EU was keen to strike a pact with Libyan leader Muammer Gaddafi to help stem the flow.

What happened next: Following the signing of the Rome-Tripoli accord, the number of people entering Italy illegally dropped to 7,300 in 2009. In 2010 Gaddafi demanded €5bn a year for Libya’s efforts, warning that Europe “could turn into Africa” as “there are millions of Africans who want to come in”.

Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to welcome Syrian refugees to Germany will be remembered by many as a noble humanitarian gesture. But other leaders were horrified by a unilateral decision that sowed divisions among EU member states, exacerbated east-west tensions and fuelled anti-establishment Eurosceptic forces.

It may have tipped the balance in favour of Brexit. It also created a civil war inside Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union from which it is still struggling to recover.

“This cannot happen again. This is on the mind of everybody,” says Camino Mortera-Martinez of the Centre for European Reform in Brussels.

The episode has left Europeans deeply divided about how much immigration is needed and how much is tolerable without harming social cohesion or national identity.

One legacy of the 2015-16 crisis has been the EU’s inability to put in place a vital missing component of its putative migration “pact”: a relocation scheme allowing member states to apportion asylum seekers and/or the financial burden. Similarly absent is a more level-headed debate about integrating refugees and using them to plug labour market shortages.

Schinas says the best way of addressing Europe’s exposure to hybrid attacks is by moving towards agreement on the pact. He adds that the EU needs to create a better-connected “circuit” of measures, including relocations of asylum seekers, financial support and the use of its Frontex border force.

“In the EU there is not a shred of doubt that migration is a common European problem and member states are pooling sovereignty, resources and more and more political will to get it sorted out as a European problem together. This will happen,” he says.

Some EU diplomats are less convinced. Member states remain deadlocked over ways of bolstering solidarity and finding ways of distributing asylum seekers entering the EU via its frontier states. Some central and eastern European countries, including Poland and Hungary, have been notably resistant to the plan. Mortera-Martinez says forcing people on to certain EU countries “is not going to happen”.

Amid the debate about managing migration internally, the EU has invested in beefing up its external controls, in what critics decry as a “Fortress Europe” policy.

It has outsourced the policing of migrant flows to regimes far less concerned about human rights standards, controversially providing financial support for the militia-backed Libyan coast guard as it seeks to reduce Mediterranean crossings. EU overseas aid is increasingly tied to border security.

The stand-off with Belarus is meanwhile hardening approaches towards asylum in the EU, analysts say. Poland, Lithuania and Latvia have all used laws or temporary decrees to curb the right to asylum as thousands of individuals sought to enter the countries from Belarus. The EU Commission on Wednesday approved rules permitting temporary suspensions of some asylum protections.

Countries including Greece have also been accused of pushing back asylum seekers, which is against international law. In early October, member states including Greece, Cyprus, Poland and Austria called in a letter to the commission for a toughening in the Schengen code, demanding that EU external borders be protected with a “maximum level of security”, including the use of EU-funded physical infrastructure. Ursula von der Leyen, commission president, has ruled out deploying EU money to pay for fences and walls.

Hanne Beirens, director of the Migration Policy Institute Europe think-tank, says the rethink on migration was “part of a wider effort by the EU to make itself less vulnerable to actions by third countries and to strike a tougher posture in broader geopolitical struggles”.

“Reviewing the Schengen border code and building fences tackles a symptom, but fails to address the underlying pull and push factors that bring migrants to Europe in the first place,” she says.

The Kremlin’s hand

Whether a more complete European migration regime would have helped defuse the Poland-Belarus stand-off is moot. EU governments have closed ranks behind Poland, despite strained relations over its rule of law breaches.

But unlike Latvia and Lithuania, whose crises on the Belarus border quickly dissipated, the nationalist Law and Justice government in Warsaw rejected help from the EU and cast itself as a sole bulwark against illegal immigration. It was a political gift. “This has the potential to win them another election,” says Mortera-Martinez.

Weaponised migration: Morocco punishes Spain (2021)

Displaced: 10,000

What happened: In May 2021 Moroccan authorities encouraged thousands of migrants to enter Ceuta, a Spanish territory in North Africa. Rabat was furious Spain had given emergency medical aid to Brahim Ghali, a pro-independence leader from Western Sahara, over which Morocco claims sovereignty.

What happened next: The crisis was eventually defused with Morocco taking back many of the migrants. Its demands for Ghali’s arrest and for recognition of its sovereignty were rebuffed.

Greenhill, the US academic, has concluded from her research that using migration as a weapon is more successful than other types of intervention, coercion or aggression.

For Lukashenko, the episode helped to distract some of the attention from the deteriorating human rights situation in Belarus after he stole last year’s presidential election, says Michal Baranowski, senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund in Warsaw.

The autocrat has spoken directly to Merkel twice in the last month, having been ostracised by western leaders since his crackdown — suggesting his efforts to get more attention from the west have met with some success.

Lukashenko has been far less successful on other fronts, including his desire to trigger a political crisis in Poland, or isolate it within the EU, or force a reversal in EU sanctions against Belarus.

Przydacz, like many others in Europe, sees President Vladimir Putin’s hand behind Lukashenko’s provocation, given the Belarusian dictator’s dependence on Kremlin support, although Russia’s direct involvement is unclear.

“One of Lukashenko’s objectives was to present Poland . . . as an inhumane country that does not observe basic principles, while Putin is giving us lessons on humanity as the president of Russia. I think every European or American reader can see the difference,” says Przydacz.

Nevertheless, many of the Middle Eastern people who amassed in Belarus remain trapped at the border, even after some have returned home. With the winter setting in it is a human misery that leaves many Europeans both deeply uncomfortable and polarised over the right response.

Through his Belarusian puppet, says Tocci, Putin “shames us in the eyes of the world”.

Source: FT