Adnan Çelik [1]

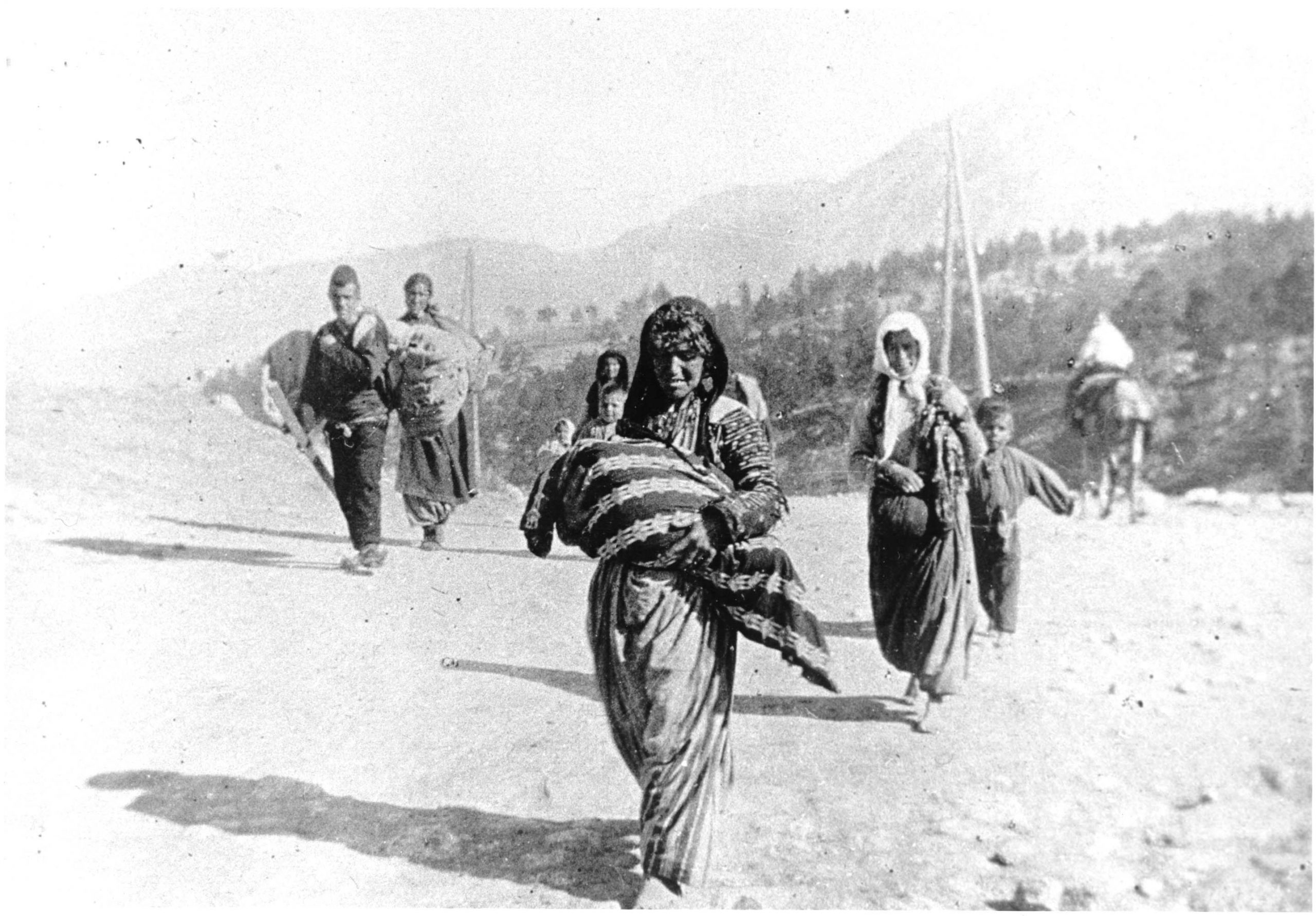

When something bad happens in Kurdistan, Turkey, it is normal to fatefully exclaim: “A curse of a hundred years!” There is no doubting the origin of this popular saying and the ghosts it evokes. It refers to the genocide of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire beginning in April 1915 by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP).[2] In the Kurdish-dominated regions, Christians (nearly a third of the population of Armenians and Assyrians) were massacred and deported with the participation of local collaborators, in the name of a ‘brotherhood of the ummah’ conceived under the banner of Islam.

This foundational crime is the subject of fierce denial in Turkey. The elites of the Turkish nation-state, since its birth in 1923, have made this denial the basis of official history, and heavily criminalised dissident voices and memories. Disseminated from the top of the state, the denialist discourse, taught in schools, soon infused the whole of society, part of which inherited the confiscated and appropriated Armenian properties. Yet in the cultural-political capital of Turkey’s Kurdistan, Diyarbakır, in 2015, thousands worked to commemorate the centenary of the genocide, the culmination of the reawakening of memory, of which Kurdistan had been the cradle for the previous two decades. The public articulation of this counter-memory is part of a wider movement awakening civil society. Since the 1990s, many social groups in Turkey (women, the LGBTI+ movement, the country’s religious and ethnic ‘minoritized’ groups) have risen up against official narratives that have obscured, invisibilised and criminalised them. They claim a history of their own, which differs from the glorious, linear and very nationalistic one imposed by the winners. Shards and fragments of diffuse memory, hitherto confined to the private sphere, now meet in the public sphere. These voices echo each other, stimulate each other, and sometimes discover a relative community of fate, that of recurrent oppression and state violence.

This is how the Armenian and Kurdish pasts come together in the same “victimo-mémorial” register. In the Kurdish region, inhabitants “remember” this Armenian warning to their Kurdish neighbours, on their way to deportation: “We are the breakfast, you will be the dinner!” More recently, did not Turkish soldiers waging war on PKK fighters in the terrible 1990s go out of their way to call them “Armenian bastards”? With the relative appeasement of the conflict and new social dynamics, the 2000s have been conducive to remembering and questioning. It appears that the mother tongue of the Kurds (long time forbidden), their toponymy (Turkishised but still in use), the stories of their oral history and, more silently, their landscapes, irremediably carry the memory of this genocide. Is it not time, then, to confront this past, to turn away from the path of exclusionary nationalisms that have so bloodied the region? In order to put an end to the “hundred years of curse”, is it not time to confront this past?

The emergence of the repressed memories of 1915 was also favoured by the ideological shift of the Kurdish movement, which dominated local politics at the time. By moving away from a Kurdish-centric prism, with a strong political project of emancipation based on the peaceful resolution of conflicts and the cohabitation of differences, it accompanied the deployment of the memory work that was taking place in the social field.

The story of the impressive deployment of initiatives relating to the multicultural past of the Kurdish-Armenian region of Turkey and the 1915 genocide, of which the city of Diyarbakır was the scene, deserves to be mentioned. Since 1999, the accession of the legal pro-Kurdish movement to the leadership of Diyarbakır’s mayor’s office, a multitude of speeches, symbols and acts have sought to bring the memory of the genocide to the conscience and public space. Between 1999 and 2015, various actors mobilised for the rehabilitation of the region’s multicultural past and the recognition of the 1915 genocide. This resulted in many initiatives, from academic research to the literary field, from the organisation of meetings, discussions and festivals to architectural, commemorative and museum undertakings, to public apologies on behalf of the Kurdish people. The commemoration that took place in 2015, in the presence of leading figures of the Kurdish movement (such as the city’s mayor Gültan Kışanak and the co-chairman of the Peoples’ Democratic Party Selahattin Demirtaş, both of whom are currently behind bars) was the culmination of this long journey.

Between 2015 and 2021, after the failure of the peace process initiated in 2013, a new offensive by the Turkish state led to the near annihilation of the efforts and achievements of this polymorphous memorial process. Since the resumption of the war against the Kurdish movement, military and judicial state violence has again been unleashed on a massive scale, not only in the Kurdish regions but also against all civil society actors who dare to raise a critical voice across Turkey. In Kurdistan, elected local authorities have been replaced by government-appointed kayyum (trustees), the epitome of state despotism. A wave of threats and condemnations led all the emblematic figures of civic and political commitment in Kurdistan, among thousands of other anonymous people, to the roads of exile or behind bars, while, on the ground, the war physically destroyed all the traces and all the symbols of the re-awakening of memory of which they had been the protagonist, in an enterprise of eradication that could be called memorycide.[3]

Since the post-2015 memorycide offensive, the Turkish state has returned to the strategic use of the judicial weapon also to suppress dissident voices questioning the official history and state denial of the Armenian genocide. These voices have been particularly strong in the Kurdish region over the past two decades, notably because of the resurgence of the legitimacy of oral history in the construction and transmission of knowledge about the past. The voices of the witnesses and the sources from oral history have played an essential role in the process of building a public discourse on the subject.

Following this state offensive, we also witnessed the return in force of a Kurdish discourse of denial of responsibility for the 1915 genocide. Indeed, we must not forget the existence of Kurdish voices hostile to this recognition process from the start. This hostility was rooted in various perspectives. Some thought that through “repentance”, the Kurds were weakening themselves and wrongly implicating themselves in the “crimes of the master” (the Turkish State, for them the only culprit). Others, partisans of a Kurdish-Kurdistan, did not want to hear about a Kurdish-Armenian past likely to taint the future homogeneity and territorial claims of classic Kurdish nationalism. Finally, others, radical Islamists, unreservedly appropriated the part of the state propaganda consisting of denouncing the Kurdish movement as a movement at the “service of Armenian and Western interests”. If these voices had been de facto marginalised and discreet during the rise of the Armenian memory rehabilitation movement, they expressed themselves without restraint after the belligerent and memorycide offensive of the government in 2015.

During the latter, the historic Sur district of Diyarbakır, which notably housed the Surp Giragos Armenian church restored with the political and economic support of the municipality and the “Monument of Common Conscience” erected two years earlier, was razed in two stages: by the army during the clashes of the 2015 “urban wars”, and then by the expropriation-reconstruction policy that followed. This last example is emblematic of the permanent desire to annihilate all traces of the former Armenian presence that has obsessed the Turkish authorities for more than a century.[4]

The brutality of the memorycide and the return of this infernal cycle of war and repression cut short the extraordinary memory work accomplished on this long road to recognition. This process was all the more unique and profound because it took place in a denialist nation-state, within a subaltern group whose actors have the particularity of also being, in part, the descendants of direct perpetrators of the genocide alongside the dominant group in power a century earlier. It deserves to be praised and recounted, not least because it shows how the recognition of the Armenian genocide, the struggle for Kurdish rights, and the possibility of democracy in Turkey remain intimately and irremediably intertwined.

Written exclusively for NAT by: Adnan Çelik

News about Turkey offers readers different points of view. The opinion expressed in this text is not necessarily shared by the editors of NAT.

[1] Adnan Çelik is a postdoctoral fellow at the Kulturwissenschaftliches Institut Essen (KWI) at the University of Duisburg-Essen and a visiting scholar at the University of Cambridge. He is part of a Turkish-Armenian Relations research project hosted by the Cambridge Interfaith Programme and funded by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. The views expressed are the author’s own.

[2] See Adnan Çelik & Namık Kemal Dinç, La Malédiction. Le génocide des Arméniens dans la mémoire des Kurdes de Diyarbekir, Translated from Turkish by Ali Terzioglu and Jocelyne Burkmann, L’Harmattan, Paris, 2021.

[3] ‘It’s memorycide’: Turkey dismantles monuments to Kurdish culture, By Tom Stevenson, and Murat Bayram, 4 August 2017, Middle East Eye, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/its-memorycide-turkey-dismantles-monuments-kurdish-culture

[4] Adnan Çelik, “The Armenian Genocide in the Kurdish Collective Memory”, Middle East Report, N° 295, (Summer 2020), https://merip.org/2020/08/the-armenian-genocide-in-kurdish-collective-memory/