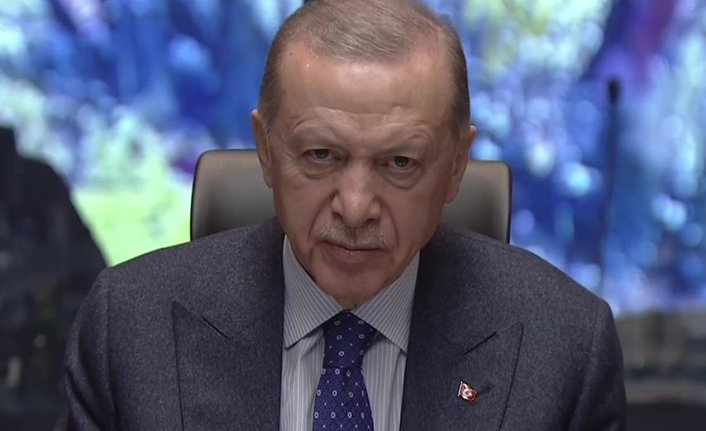

When Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan assumed sweeping powers in 2018, he swore the state would deliver more under a centralized system that his critics compare to one-man rule.

Five years on, an agonizingly slow response to a catastrophic quake has undermined that idea, boosting the opposition’s case in polls planned for May, experts say.

Erdoğan has acknowledged “shortcomings” in the government’s handling of Turkey’s deadliest disaster of its post-Ottoman history.

More than 36,000 people have died in Turkey and nearly 3,700 in neighboring Syria. The toll is expected to keep climbing for days to come.

Under pressure unseen before in his two-decade rule, Erdoğan blamed obstacles such as freezing temperatures and quake-damaged airports and roads.

No government in the world could have done better, Erdoğan said.

The opposition counters that the February 6 quake underlines why Turkey must switch back to a parliamentary system under which agencies have more freedom to act on their own.

“You have centralization in all Turkish institutions, which is reflected in institutions that specifically should not have it,” such as the disaster agency, said Hetav Rojan, a disaster management expert who follows Turkey closely.

‘Critical hours’

Rojan argued that the system, which Erdoğan secured through a constitutional referendum in 2017, had hamstrung disaster response agencies that need to make snap decisions on their own.

Help took days to arrive in many areas, with distressed residents forced to use their bare hands to try and pull relatives from the rubble.

Others were left without water, food or shelter in freezing temperatures.

Many volunteers who rushed to the region shared on social media how they were forced to wait for authorizations or how equipment was slow to arrive.

The government has since dispatched tens of thousands of soldiers to the scene, reinforcing support for millions of people left homeless by a 7.8-magnitude quake.

But many are still angry at the initial delay.

The main opposition leader, who is running neck-and-neck with Erdoğan in opinion polls, has spearheaded the criticism.

“There wasn’t any coordination. They were late in the critical hours,” Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu said this week.

“Their incompetence cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of our citizens.”

Unseemly arguments

For example, it was impossible for crane operators — who offered critical assistance to rescuers — to be deployed without the disaster agency’s approval.

This cost crucial time, Erdoğan’s critics say.

Others point to unseemly arguments between state agencies and independent rescue and relief workers on the ground.

AFP journalists witnessed disputes between volunteers and AFAD state disaster responders in Elbistan, near the epicenter of a huge aftershock in Turkey’s southeast.

“We started working on this rubble even though the disaster agency discouraged us from it,” a volunteer, who did not wish to be named for fear of retribution, told AFP.

“When we finally heard the voice of a survivor, AFAD teams pulled us away and took over our work,” he added.

Murat, 48, waiting for news of his loved ones under the rubble in Kahramanmaraş, witnessed similar scenes.

“When miners discovered a person alive under the rubble, they were pushed away and people who wanted to appear on camera took their place,” he said, also fearing to disclose his last name.

Controlling the narrative

Even a non-profit group run by rock star Haluk Levent as well as opposition-run municipalities that sent in their own rescue teams have provoked the government’s ire.

“The necessary actions will be taken against anyone that tries to rival the state,” threatened Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu.

“The [ruling party] government and its institutions are really trying to control the narrative of the current rescue management,” Rojan said.

An advertising campaign called “disaster of the century” had been prepared by an agency close to the government, Turkish media reported.

The aim, critics say, was to convince Turks that any shortcoming is because of the gigantic size of the disaster — that no one could handle such a catastrophe.

In the face of a public outcry, the campaign was withdrawn.

For Rojan, it’s still “too soon” to see if the government’s narrative will work.

“It is definitely a political test for Erdoğan with upcoming elections,” he said.

© Agence France-Presse