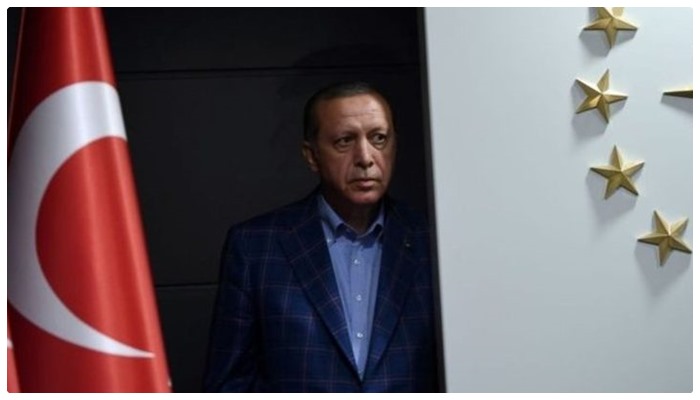

When a leader stays in power for as long as Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, it is almost inevitable that their rule becomes a regime. Erdogan has led Turkey for 20 years: No other Turkish leader has survived longer, and no Turk born after the turn of the millennium can remember a time without him. Since crushing an attempted military coup in 2016 Erdogan has purged the state and armed forces, tamed the judiciary and central bank, locked up opponents at home and hunted down those overseas, and ousted dissenters from his party. Yet he must still face the ballot box.

Erdogan centers his populist rhetoric around “the will of the people” and leans on majoritarian democracy. It is unthinkable to Turks that he would cancel elections, and even the devastating February earthquakes, which are confirmed to have killed at least 50,000 people to date and have displaced millions, have not delayed the May 14 polls.

Erdogan’s eagerness to keep elections to schedule is partly because he is racing against time on the economy. The central bank has burned through billions of dollars buying lira to keep the currency afloat over the past year, and Turks are increasingly reliant on loans and credit cards as inflation that topped 85.5 percent in October 2022 sent prices of basic goods soaring. In the short term, the president is relying on cash injections from Russia and the Gulf to keep reserves topped up, but in the meantime, private foreign investors are fleeing Turkey. His foreign policies have brought Turkey closer to Russia but left it largely isolated within its region for much of the past decade, due to his support for Muslim Brotherhood-linked groups in the aftermath of the Arab Spring.

Erdogan’s Toughest Test

Erdogan continues to win the devotion of a steadfast third of the country, but the May 14 presidential and parliamentary elections will be the toughest elections he has faced since 2003, when he first took power as prime minister. The broad base he built in his first decade included Kurds, pro-democracy liberals, and the economic elite, but they have drifted. The collapse of the Kurdish peace process, Erdogan’s swerve into autocracy, and the tanking economy have all taken chunks out of his support.

The opposition’s task now is to reel in disenchanted voters to win by a margin big enough that the results are indisputable. For them, the earthquakes are an opportunity. As campaigning gets underway, polls show Erdogan’s main contender for the presidency, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, leading by a couple of percentage points. An opposition coalition is currently projected to take a slim majority in the parliament, although Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) is likely to remain the single biggest party.

“Free But Not Fair”

Figures within the opposition say they expect interference. Erdogan has fine-tuned methods of electoral micromanipulation over the past decade, using his sway over the courts, higher electoral board, and the media, and nudging results enough to shift fine margins without blatant displays of cheating. In the last round of national elections in 2018, OECD observers concluded that the polling was “free but not fair.”

Newly-passed election rules could help Erdogan this time. On May 14, ballot boxes will be stationed in Turkish embassies in 75 countries around the world, 15 more than in 2018. The diaspora in countries like Germany, where around 1.4 million Turkish citizens are registered to vote, leans toward Erdogan, although turnout is usually low. It is still unclear how ballot boxes will be organized in the places worst hit by the earthquake, where two million people have been displaced; voter registration closed on March 17, with many people still living in emergency accommodation.

Recent changes to rules governing how seats in the parliament are distributed mean that the four smaller parties in the “Table of Six” opposition coalition will struggle to win seats in the parliament, though they could get around the rule by running their candidates under one of the coalition’s two biggest parties, Kilicdarogu’s secularist Republican People’s Party (CHP) or Meral Aksener’s nationalist Iyi Party.

Divide and Rule Politics

Presidential races have turned into charisma contests since 2014, when Erdogan stood down as prime minister to run as Turkey’s first popularly-elected president. He uses jeopardy as a key weapon in his populist arsenal on the campaign trail and since 2015, when he took his AKP into an alliance with the hard-nationalist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), he has turned to divide and rule politics.

Opponents of all stripes are labelled enemies, be they journalists, politicians, or artists. Critical news channels have been closed down or forcibly taken over by Erdogan’s allies in the business sector, and thousands of dissidents are in jail or exile. With no such thing as purdah, Erdogan has recently announced pension rises and a massive rebuilding program in the earthquake-struck south. Rows with Western countries, such as that over Sweden’s NATO membership, make good electoral fodder for Erdogan, who tells his domestic audience that he is standing up for Turkey’s interests on the world stage.

At the political level, Erdogan’s wide crackdowns have backfired, bringing together parts of the opposition that were previously antagonistic to each other. Supporters of all parties, from the Kurdish-rooted Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) to the CHP have been targeted with terror or coup-plotting accusations.

The Kurds, considered the kingmakers in Turkish politics, have long been suspicious of the CHP due to its links with Kemal Ataturk, founder of the Turkish republic, who launched his own violent crackdown on Kurdish separatism in the 1920s, and in recent years the CHP has largely supported Erdogan’s military operations against Kurdish militants both at home and in Syria and Iraq. But in 2019 Ekrem İmamoglu, the CHP’s candidate for mayor in Istanbul’s local elections, managed to secure the support of the HDP to overcome Erdogan’s attempt to block him from office. In March the HDP announced that it would not be running a candidate in May’s presidential elections in order to support Kilicdaroglu. The opposition also learnt other ways to fight back in recent years, including by organizing an army of volunteer ballot box monitors in Istanbul in 2019.

There are brakes on campaigning this time around. In a mark of respect for victims of the February earthquakes, rallies will be held without music and no party has yet commissioned a song, normally a standard part of any campaign. In previous years that would have deprived Erdogan of his trump card, but his appearances have been lackluster in recent years, and members of his campaign team may fear public displays of hostility toward him due to anger over the government’s bungled response to the earthquake. Foreign spats have lost their potency as Turks have become more concerned about economic woes. The president still has the upper hand on the traditional airwaves, although the opposition is far savvier on social media.

No Immediate Changes

Should the opposition beat Erdogan—and this is undoubtedly their best chance in 20 years to do so—little will change immediately. The Table of Six has pledged to take Turkey back to a parliamentary system but this will take time and require a two-thirds majority of MPs. Relations with the West may well pick up, but it is unlikely that an opposition government would break Turkey’s business ties with Russia.

Win or lose, an economic crisis is inevitable: Credit will need to be tightened and interest rates raised, and the lira will lose more of its value. Most pressing and complex of all, state institutions will need to be reformed in order to remove the Erdogan loyalists who have been installed in key positions in recent years and return the bureaucracy to non-partisanship.

The biggest question is whether legal action should be taken against Erdogan and his closest allies. Doing so could galvanize his supporters and set the scene for attempts to overturn the democratic process, as occurred in Brazil and the United States.

By: Hannah Lucinda Smith – Istanbul correspondent for The Times of London.

Source: Internationale Politik Quarterly