Turkish opposition leader and presidential candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu’s declaration of his Alevi identity sparked multiple reactions from President Erdogan and beyond.

On April 19, turning to Twitter Kilicdaroglu made a bold declaration: “I am an Alevi” The news was no secret, but the video of his declaration quickly went viral, garnering over 100 million views in three days.

Turkey is gearing up for historic elections on May 14th, which will determine both the composition of parliament and the presidency. The majority of opinion polls indicate that Kilicdaroglu holds a lead over Erdogan, whose party has been governing the country since 2002. As I previously argued, identity politics and political fault lines are among the key factors shaping the election, surpassing the importance of the country’s economic state.

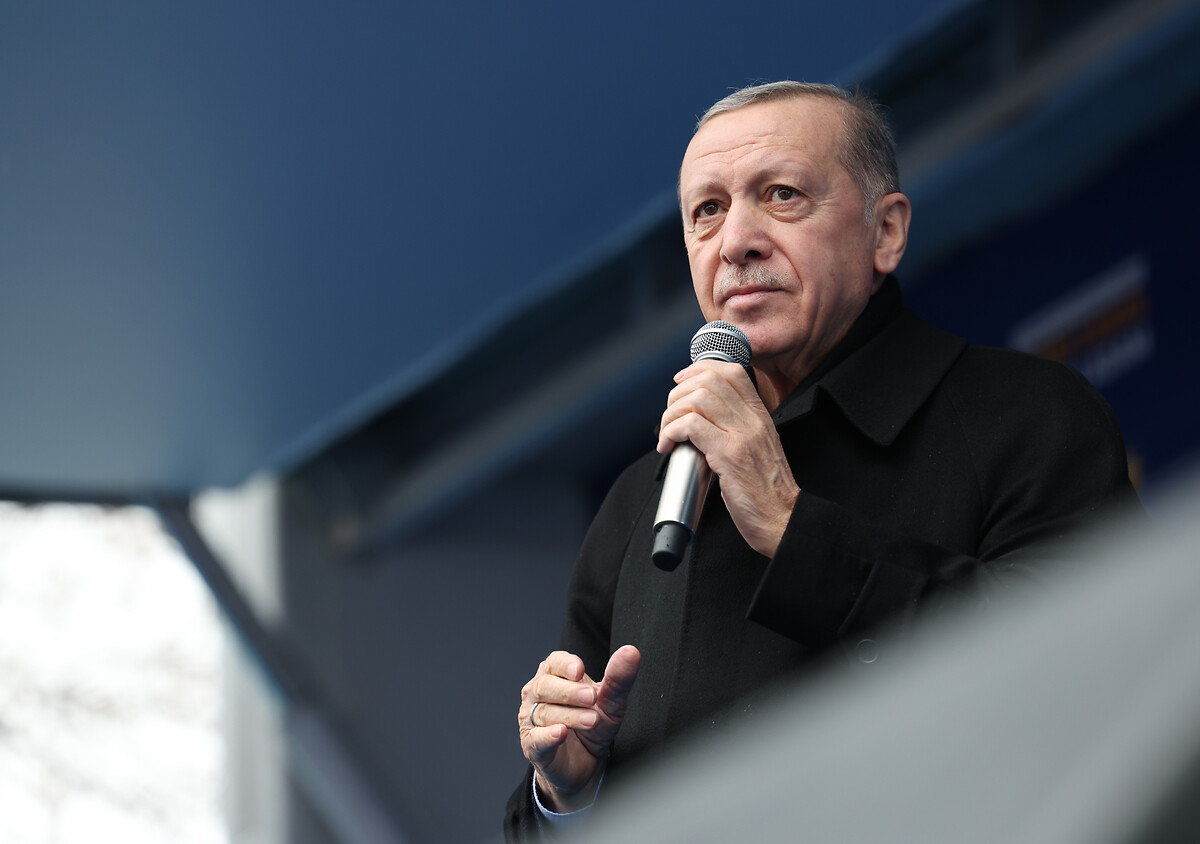

Following Kilicdaroglu’s video message, Erdogan held an unusual de-facto election rally within the restored Sultanahmet Mosque compound, (called Blue Mosque by tourists owing to the mosque’s blue, green and white tiles). He employed rhetoric aimed at questioning the main opposition bloc’s religious credentials, falsely accusing them of proposing to shut down Turkey’s religious directorate.

Two days after his announcement, Kilicdaroglu faced provocative verbal attacks on his Alevi identity during a visit to an earthquake zone. In the face of such reactions, President Erdogan also sent positive messages, highlighting his record of positive steps towards Alevis. Erdogan’s search for the right tune to counter Kilicdaroglu’s declaration remains ongoing.

Both modern and pre-modern Turkish history are marred by massacres against Alevis, with five significant incidents occurring over the last century. In 1937 and 1938, Alevi-Kurds in Dersim province faced large-scale massacres, prompting among other things, a name change to Tunceli. In 1978, over a hundred Alevis in Kahramanmaras died at the hands of right-wing paramilitary forces. In 1980, numerous Alevis, mostly women and children, were killed in Corum. In 1993, 37 people were killed during an Alevi festival in Sivas. In 1995, Alevis in Istanbul’s Gaziosmanpasa neighborhood were attacked by unknown assailants, followed by police repression of left-wing Alevi protesters.

Erdogan’s political record regarding Alevis

Erdogan’s tenure has seen no such massacres of Alevis. Erdogan became the first president to officially recognize Alevi prayer houses, although not as places of worship, and established a new public coordination agency under the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

However, despite starting as a reformist and, to some extent, pluralist leader in the mid-2000s, President Erdogan has not initiated proper reforms to improve the situation of Alevis. The Alevi issue remains one of the most unsuccessful aspects of Erdogan’s political record.

Previously, Erdogan sought to coax Kilicdaroglu into revealing his Alevi identity, but the opposition leader refused to take the bait. Now that Kilicdaroglu has voluntarily declared his identity, the political landscape in Turkey is evolving.

Kilicdaroglu’s Bold Move: Challenging the Status Quo of Minority Identities in Turkish Politics

A daring statement echoes. The sheer scale of the reaction to Kilicdaroglu’s announcement highlights its importance in a nation where minority identities have traditionally been understated, especially among prominent public figures. This is remarkable considering that Kilicdaroglu’s identity was already publicly known, and his background had been exploited by individuals from both sectarian Islamist and secularist, yet sectarian, factions

Overwhelmingly positive responses flooded in from Sunni-majority Twitter users. Surprisingly, the platform amplified these messages in a polarised society.

Past Turkish leaders concealed their minority identities. Turgut Ozal, a former prime minister and president, had Kurdish ancestry, but never publicly acknowledged it. Currently, several figures in Turkey’s political and bureaucratic leadership, are reportedly of non-Turkish origin. Nevertheless, their heritage remains unspoken.

The reluctance to openly discuss minority identities extends beyond politics, as seen with top journalist Mehmet Ali Birand revealing his Kurdish origins only months before his death. This pervasive avoidance of identity discussions, however, does not mean that discrimination does not exist.

Discrimination in Turkey is veiled, never officially acknowledged. Political rhetoric claims no discrimination, asserting the state’s blindness to identity. In reality, the state sees all.

#MeToo moment for Turkey’s Alevis?

Kilicdaroglu’s declaration has been hailed as a turning point in Turkish politics, prompting thousands of Alevis to share their experiences of discrimination and suffering on Twitter. These testimonies expose a pattern of discrimination that typically occurs behind people’s backs, rarely confronting individuals directly. This moment of openness could be likened to a #MeToo moment for Turkey’s Alevis.

Unlike the #MeToo movement, high-profile Alevi public figures have not yet revealed the extent of discrimination they faced or witnessed.

Kilicdaroglu’s announcement carries more weight than those of lesser-known Alevis, as it is exceptionally rare for someone in a position of power in Turkey to openly declare their Alevi identity. The overwhelmingly positive responses he received from majority Sunni users on Twitter demonstrate that, despite Turkey’s polarised society, more peaceful and positive messages can still resonate.

Kilicdaroglu’s critics argued no discrimination exists against Alevis, accusing him of inciting sectarian policy. By bringing his identity to the forefront, Kilicdaroglu potentially aimed to disarm potential attackers, diminishing the impact of their accusations. This strategy could foster a more inclusive political discourse, pushing back against the religious bigotry that often plagues Turkish politics. While the road to dismantling long-standing prejudices is arduous, Kilicdaroglu’s declaration may represent a crucial step towards fostering greater tolerance and understanding in Turkey’s political landscape.

Alevis are often seen as a branch of Islam loyal to Prophet Mohammed’s family and the fourth caliph Ali, with a more liberal perspective on gender equality than other Islamic sects. They are distinct from Shi’as and Syrian Alawites, with some considering Alevism as a belief in itself.

Critics of Kilicdaroglu argue that there is no discrimination against Alevis in Turkey, accusing him of promoting sectarian policy.

Political fault lines run deeper than geological fractures

Turkey grapples with the aftermath of massive earthquakes that struck on 6th February, unable to provide basic shelter for many survivors. The seismic activity exposed again the deep geological fault lines. In the aftermath of Kilicdaroglu’s declaration, Turkey’s deep political fault lines, some coinciding with religious and ethnic identities, have been laid bare again.

The intense debate surrounding religious and ethnic identities at the center of the election discourse suggests that the nation’s political fault lines, run even deeper than these geological fractures. As Erdogan grapples to find an appropriate response to this unprecedented declaration, the evolution of Turkish politics is well underway, and the impact of Kilicdaroglu’s announcement remains to be seen. However, the positive responses from conservative Turkish Muslims indicate that these divisions could be healed.

By: Güney Yıldız

Source: Forbes