The European Union (EU) and Turkey said on Friday they will keep working toward modernizing their long-stalled customs union, a push Ankara increasingly frames as urgent as Brussels advances new trade agreements that can reshape competitive conditions for exporters tied to the EU market but outside its deal-making.

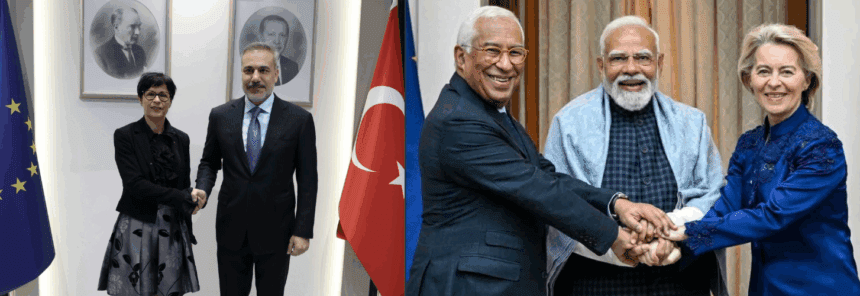

The renewed message came after Marta Kos met Hakan Fidan in Ankara and the two issued a joint statement saying they would continue engagement to improve implementation of the existing customs union and work toward paving the way for its modernization. They also welcomed the gradual resumption of European Investment Bank operations in Turkey and said they intended to strengthen cooperation on EIB-backed projects in Turkey and nearby regions.

The customs union, in force since 1995, allows tariff-free circulation for most industrial goods between Turkey and the EU, but it does not cover services, public procurement, or most agricultural commerce. Turkish officials and business groups have long criticized the structure as asymmetric, arguing it leaves Turkey exposed to shifts in the EU’s external trade policy while limiting Ankara’s ability to secure matching access in third-country markets.

That asymmetry has gained new urgency in Ankara after the EU’s recent trade breakthrough with India. On January 27, the EU and India announced the conclusion of a landmark free trade agreement, with headline terms that would eliminate or reduce tariffs covering 96.6% of EU goods exports to India (by value) and liberalise around 99.3–99.5% of EU tariff lines for Indian goods, phased in over time.

If implemented as outlined, the EU–India deal could produce two parallel effects that matter for Turkey. First, it is designed to unlock significant new opportunities for European exporters in a market where tariffs have been a major barrier, particularly in sectors such as automobiles and other industrial goods, potentially redirecting some EU firms’ investment and supply-chain planning toward India. Second, it can increase competitive pressure inside the EU market as Indian exporters gain improved preferential access on a wide range of products over the phase-in period, strengthening “preference erosion” concerns voiced by Turkish critics of the current customs-union model. As the EU expands its network with major partners, Turkey’s position becomes harder to sustain politically and economically unless the customs union is updated or Turkey secures equivalent arrangements.

Brussels and New Delhi have presented the agreement as strategically significant as well as commercial, but its timeline still depends on legal review and approval steps on both sides. The deal would require legal vetting and could take around a year to implement. Until then, much will hinge on technical details such as rules of origin and the sector-by-sector sequencing of tariff cuts, which can determine how quickly preferences translate into real shifts in sourcing and pricing across EU supply chains.

The EU–Turkey statement on Friday also touched areas that have become part of a broader “re-engagement” agenda, including mobility and sanctions enforcement. Turkey has repeatedly urged smoother access to Schengen visas, and EU institutions have pointed to the “cascade” system introduced in mid-2025, which can allow longer-validity, multiple-entry visas for applicants who meet prior-travel conditions, as a step to ease travel for frequent, law-abiding applicants. At the same time, EU statements have continued to link closer economic cooperation to rule-of-law expectations and to preventing circumvention of EU sanctions—issues that have contributed to the long freeze in Turkey’s EU accession process despite its formal candidacy status.

In Turkey, calls to upgrade the customs union have drawn support across the political spectrum. Ekrem İmamoğlu, a leading opposition figure currently jailed, urged EU leaders this week to move faster on modernization, arguing the current framework harms Turkish industry and deepens structural imbalances, while presenting an updated customs union as part of a broader reset that he said could follow democratic reforms after an opposition election victory.

For now, Friday’s language signals intent rather than a breakthrough: both sides spoke of improving implementation and “paving the way” for modernization, but formal negotiations would still require political decisions in the EU. Still, the timing—immediately after the EU–India deal—underscores Ankara’s core argument that every major new EU trade agreement increases the economic cost of leaving the EU–Turkey relationship anchored in a 1990s framework.