Past dithering on inflation is hampering the Turkish central bank’s ability to prop up the weakening economy.

While the lira crashed and prices soared over the summer, Governor Murat Cetinkaya and colleagues hesitated until September before finally raising interest rates. The legacy of that delay means the central bank is trying to quell inflation and keep investors on side for fear of unsettling the currency even as Turkey slides toward recession. The result: an economy painfully squeezed by real rates that Morgan Stanley estimates are double the level for emerging markets as a whole.

“There is now zero scope for monetary policy experimentation,” said Timothy Ash, a strategist at BlueBay Asset Management in London. “In effect the central bank now has to rebuild its credibility by maintaining a hawkish policy stance for longer than perhaps the underlying data might suggest.”

The bank hiked borrowing costs only after investors dumped the lira — in part because they worried that policy makers, who’ve balked in other times of crisis, weren’t doing enough to control prices. As authorities increasingly take their cue from the market, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has dialed back pressure on the central bank to reduce borrowing costs.

The Turkish leader, who once declared himself an “enemy of interest rates,” has instead resorted to market interventions to control price increases. He’s gone as far as deploying police to monitor stores and sending officials to inspect onion warehouses.

But given the track record of political interference, the damage was done. The central bank’s credibility as an independent regulator has yet to fully recover after policy makers under pressure to keep rates low held back at a time of extreme market turmoil.

With the central bank’s hands tied, the economy faces an uphill climb. On an annual basis, gross domestic product probably contracted last quarter and is on track to shrink through the first half of this year, according to the median forecasts compiled by Bloomberg. And instead of a growth spurt that Turkey experienced after the past two recessions, its rebound this time may be far more gradual.

Still, monetary easing in Turkey remains a question of when, not if. While price growth has decelerated by almost 5 percentage points in the past three months, and the central bank is projecting an even bigger decline by year’s end, the benchmark rate has stayed at 24 percent since an increase of 625 basis points in September.

“The real test will be when inflation declines significantly, likely late in the second quarter,” said Credit Agricole SA strategist Guillaume Tresca. “The central bank has regained some credibility but it is still fragile. It takes months to reassure markets.”

Relief won’t be in sight any time soon if concern over investor perception continues to set the tone for the central bank’s actions. Easing won’t start until the second quarter, with the key rate ending this year at 20 percent, according to the median forecasts of economists polled by Bloomberg.

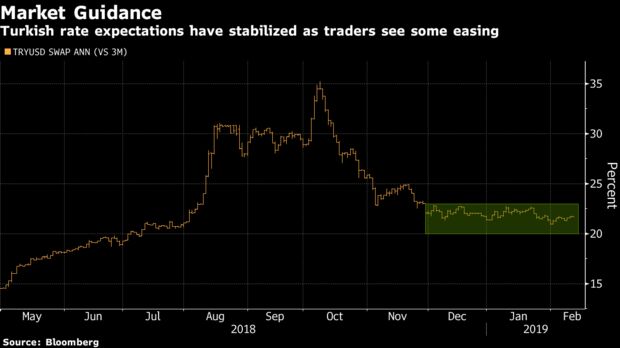

Traders are mostly on the same page. The one-year dollar-lira swap has hovered around 22 percent since December, which suggests the market has priced in at least 300 basis points of cuts over the next 12 months.

If the market’s expectations are at odds with the official view, “it could prove difficult for the central bank to signal an interest-rate cut without potentially undermining the lira’s stability, which is a crucial factor to maintain inflation on the downside trajectory,” said Rabobank strategist Piotr Matys.

“One could argue that policy makers guide market expectations — not the other way round,” he said. “For this notion to be valid, a central bank needs very high credibility.”

— With assistance by Onur Ant

Source: Bloomberg