Bulgarian author of new book on President Erdogan’s 20 years in power tells BIRN that, despite his growing unpopularity, Erdogan has ‘plenty of tricks up his sleeve’ – and won’t be displaced easily.

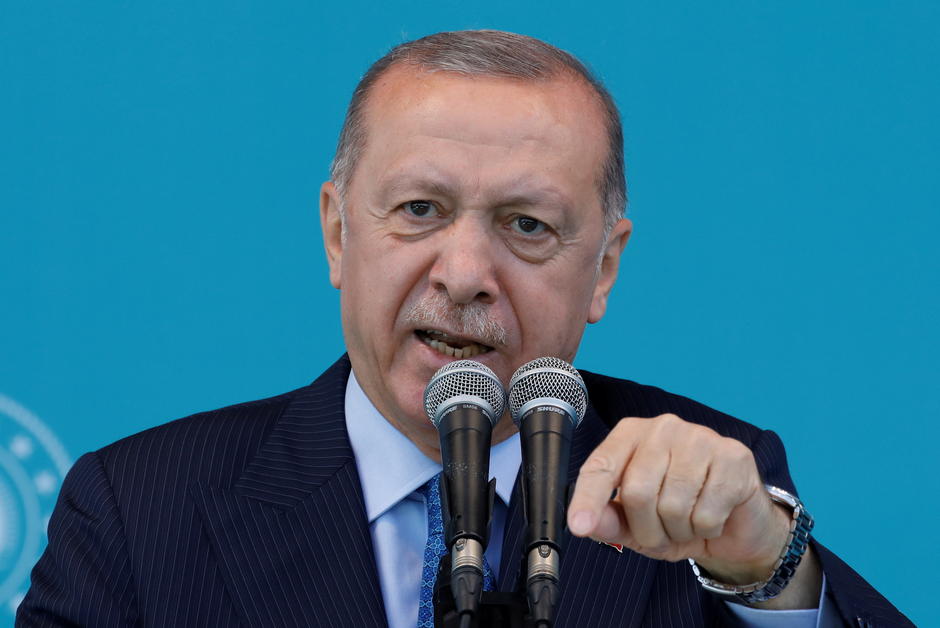

Arecently published book, Turkey under Erdogan: How a Country Turned from Democracy and the West, by Bulgarian author Dimitar Bechev, tells the story of how Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan became an autocrat – and how he has maintained his power for nearly 20 years at the expense of freedom and democracy while also shifting the axis of Turkish foreign policy.

An experienced scholar and specialist in the Balkans, Eastern Europe, Russia and Turkey, Bechev has worked on both sides of the Atlantic at universities and think tanks.

Currently affiliated with Carnegie Europe, he now lectures at the School of Global and Area Studies at Oxford University in Britain.

His latest book, published by Yale University Press, and whose previous books include Rival Power: Russia in Southeast Europe, is already hailed as an important addition to Turkish and European scholarship.

“A sweeping attempt to capture the last 20 years of Turkey, Bechev skilfully traces the radical transformation of Turkey’s domestic and foreign policies under Erdogan. An outstanding book from one of the best,” wrote Gonul Tol, Director of Turkey Programme at the Middle East Institute in Washington.

Bechev told BIRN in an interview that he decided to write the book after witnessing and following the rise of Erdogan’s autocratic rule and erosion of democracy.

“Over many years, I have been engaging with scholars from Turkey and thinking about Turkish foreign policy. At my past job at the European Council of Foreign Relations, ECFR, I covered Turkey at a crucial period,” he recalls.

Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party, AKP, “had won its third term in office in 2011, and before that there was the constitutional referendum. There was also the time of the Arab Spring and Turkey’s response was a crucial part of the story,” Bechev says.

Years of research and writing on Turkey, visits there and talking to people from the country, all fed into the project.

“That very much informed my decision to put down my thoughts in a book and think about what happened over this two-decade period, going back to 1990s and late-1980s,” he explains.

‘Golden years’ of prosperity

Bechev’s 250-page book comprises 10 chapters besides an introduction and epilogue. In it, he focuses on the breaking points in local and international politics that shaped Turkey over the last 20 years.

Bechev describes Erdogan’s first years in power as his “Golden years”.

“That is how it felt, and how people reacted to Turkey at the beginning of the AKP’s time in office. It was golden in the direct sense of the word; you don’t even need to go into metaphors,” Bechev says.

Unlike today, Turkey was moving firmly on a European path, becoming a candidate for EU membership in 2004. The economy was booming, Turkey was opening up to the world, the direction of the country led towards democratisation and Turkey was widely seen as a reliable partner to the West.

“Erdogan’s AKP was also a vast coalition of very different actors: from Islamic conservatists to liberals, from the business sector to the Kurdish movement,” Bechev notes. “The sky was the limit in terms of optimism about Turkey.”

However, things changed, and the optimism felt about Erdogan was proved wrong.

Bechev said the change in EU leadership, Nicolas Sarkozy’s rise to power in France – his suspicions about Turkey’s EU membership –moves to shut down Erdogan’s AKP party, and the departure of various members of Erdogan’s coalition as a result of disagreements with AKP policies, were the main breaking points, ending those “golden” years.

“Clearly, after the closure case that the AKP faced in 2008, the AKP came to a conclusion that the only way to survive was just to stay in power, no matter what,” Bechev says.

The birth of an autocrat

“People have taken the line that Erdogan had a grand plan from the start, that people like myself and my colleagues were too naïve, and he was a wolf in sheep’s skin. Maybe there is an element of truth in that. He was always an authoritarian personality,” Bechev concedes.

However, Bechev underlines that the change was not only down to Erdogan’s personality; structural conditions allowed him to develop and build a regime in his own image.

“The AKP transformed from pluralistic leaders like [former president] Abdullah Gul and [former speaker] Bulent Arinc who shared power with Erdogan,” Bechev says.

Erdogan later expelled them from his party, making himself the supreme leader.

Bechev adds that the deterioration of media freedom, increasing polarisation in society due to Erdogan’s increasingly Islamist policies, the rise of nationalist discourses and the failure of talks with the Kurds were all important drivers behind Erdogan’s emergence as an autocrat.

“External actors were also instrumental. When the EU dropped Turkey [as a likely member], the country turned backwards. So, there are a lot of ingredients – of personality, institutions, ideology and internal-external dynamics,” Bechev says.

Another important element in building Erdogan’s regime was his cooperation with Fethullah Gulen’s movement.

The Turkish preacher, who has lived in exile in the US since 1999, once supported Erdogan, using his supporters in the state, police and judiciary to overwhelm the old secular establishment.

“They had to take over a state machine that never belonged to them. Gulenists were part of this enterprise, in the sense that they provided the cadre of qualified people to run ministries and departments of states,” Bechev explains.

According to Bechev, the Gulenists’ power in state institutions then became a security issue for Erdogan’s government.

“It was a marriage of convenience. But Erdogan realised that there was no way that he could sustain this partnership,” Bechev says.

“Future generation of historians will tell us what really happened between Gulen and Erdogan, including the coup attempt in 2016. Erdogan needed Gulen in his fight against the establishment. But as time went on, cracks appeared and then become more open,” Bechev says.

The Erdogan government has accused the exiled Gulen and his network of operating a parallel structure within the Turkish state and of orchestrating the failed coup attempt in July 2016.

Gulen has dismissed the accusations.

According to the Turkish Interior Ministry, since the failed coup, more than 15,000 Turkish armed forces members, 31,000 police officers, more than 4,000 gendarmerie officers and 348 coastguards have lost their jobs over alleged links to Gulen.

A total of 292,000 people have been detained for alleged links with the Gulen movement and more than 30,000 people are in prison for the same reason. More than 125,000 public servants have been dismissed from office.

Turkish opposition and rights groups have accused Erdogan of using the failed coup to target his critics and consolidate his rule.

“We know only the tip of the iceberg. Gulenists were among the initiators, but were not the only players in this complex dynamic,” Bechev says.

Downfall may not be inevitable

Many local and international experts believe Erdogan’s fall is inevitable, given the increasing popular opposition, his endless domestic and international quarrels, and most importantly, the bad shape of Turkey’s economy.

In recent polls, Erdogan’s coalition lags behind the opposition.

Bechev thinks differently. “There is an optimism in Turkey [about the fall of Erdogan] but I think that he is much more resilient,” he says.

“I hope I am wrong, but it seems to me that the stakes for Erdogan are so high that he does not really have an exit option.”

If he falls, “he will either face justice and to prison or he will go somewhere like Qatar in exile”, Bechev continues.

Bechev thinks Erdogan will fight to the end to stay in power, underlying the importance of election trickery, attempts to divide the opposition, and the strength of Erdogan’s media power.

“He has quite a few more tricks before he leaves. I am afraid for the day before the election day and after. I do not know what will happen next year in Turkey [when elections are due], but I am afraid that there is a scenario that he will stay in power while the legitimacy of the elections remains in question,” Bechev says.

He concludes: “I am not sure his downfall is imminent. I don’t think the regime is sustainable in the longer term, but it might not be the next year before we see an end to it.”

Hamdi Firat Buyuk

Source: BIRN