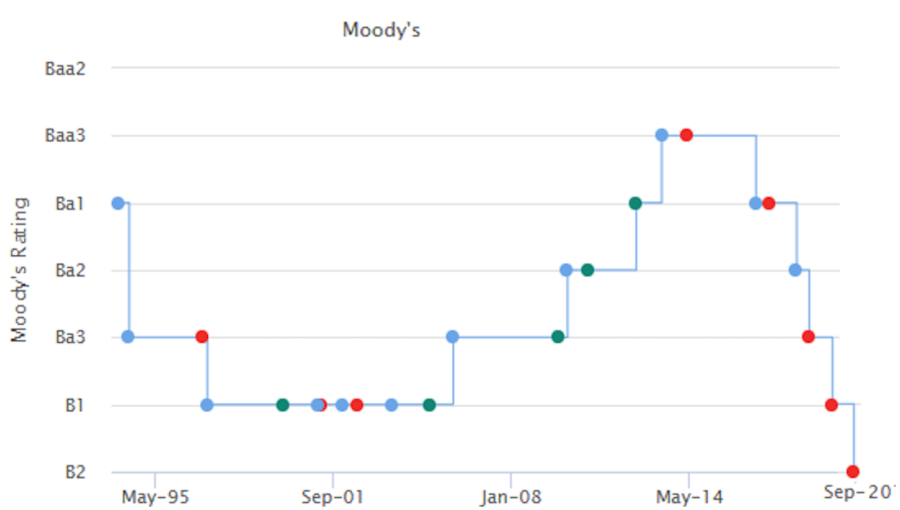

Turkey’s Moody’s grade is at its lowest level since the country received its first rating from the agency at the beginning of the 1990s. (Chart by @e507)

Moody’s Investors Service has downgraded its rating on Turkey by one notch to B2, taking it to five notches below investment grade, while maintaining the Negative outlook, the rating agency said on September 11 in an unscheduled rating action.

The action was prompted by the recent deterioration in Turkey’s external fundamentals. It made a balance of payments crisis more likely and therefore put pressure on the previous B1 rating, Moody’s noted.

In June, Moody’s passed a scheduled rating review for Turkey with no action.

In August, it warned Turkey over its erosion of reserves.

On September 8, Moody’s rating committee was assembled to discuss Turkey’s rating, the rating agency said on September 11.

“Who’da hell are you yaa?” (by @mcllkk). Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s critics didn’t take long to respond to the latest sour economic news.

The main points raised during the rating committee discussion, as noted in the Moody’s September 11 statement, were:

– The issuer’s economic fundamentals, including its economic strength, have materially decreased.

– The issuer’s institutions and governance strength have materially decreased.

– The issuer has become increasingly susceptible to event risks.

– Other views raised included: The issuer’s fiscal or financial strength, including its debt profile, has not materially changed.

Moody’s cited three key drivers for the downgrade:

1. Turkey’s external vulnerabilities are increasingly likely to crystallise in a balance of payments crisis.

2. As the risks to Turkey’s credit profile increase, the country’s institutions appear to be unwilling or unable to effectively address these challenges.

3. Turkey’s fiscal buffers are eroding.

The maintenance of the negative outlook reflects Moody’s view that fiscal metrics could deteriorate at a faster pace in the coming years.

It also reflects the downside risks associated with the authorities’ inadequate reaction function, which makes Turkey more likely to suffer a full-blown balance of payments crisis in the coming years.

Finally, it reflects elevated levels of geopolitical risk on several fronts.

Moody’s also lowered Turkey’s foreign currency deposit ceiling by one notch to Caa1, two notches above default and seven notches below investment grade, from B3.

The short-term foreign currency bond ceiling and short-term foreign currency deposit ceiling both remain unchanged at Not Prime (NP).

Ceilings generally act as the maximum ratings that can be assigned to a domestic issuer in Turkey, including for structured finance securities backed by Turkish receivables, Moody’s noted.

The alignment of the foreign currency bond ceiling and the government bond ratings reflects Moody’s view that exposure to a single, common threat—loss of external confidence and capital—means that the fortunes of public and private sector entities in Turkey are, from a credit perspective, increasingly intertwined.

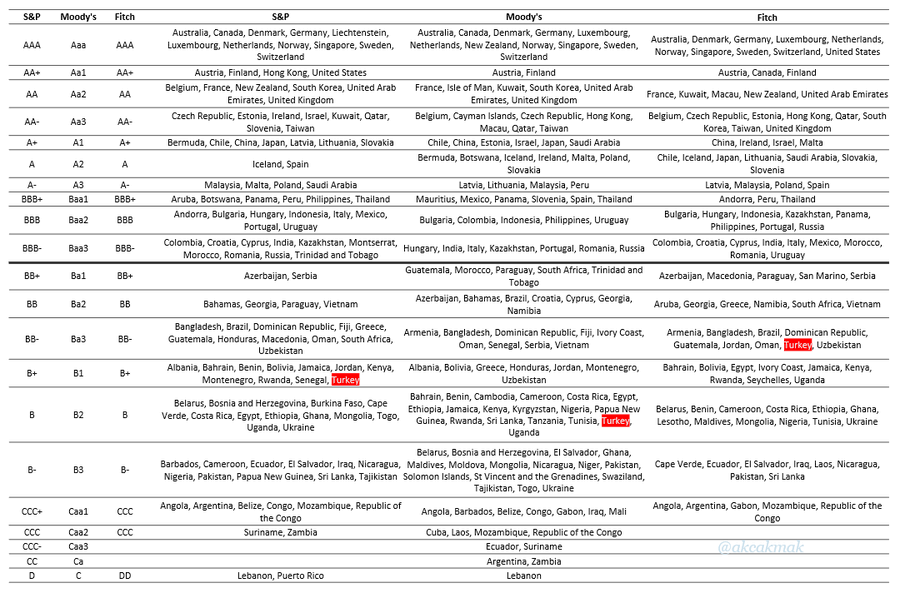

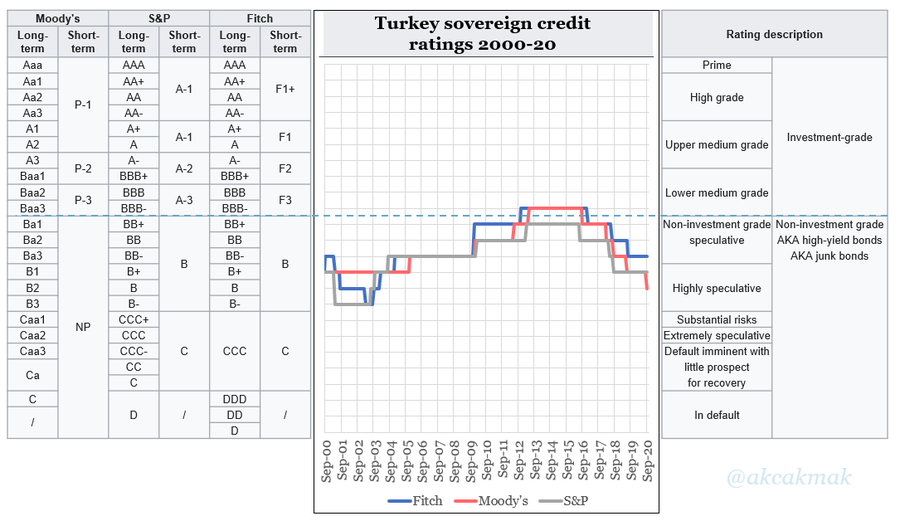

“To put things into perspective, Moody’s rating downgrade pushes Turkey further away from other major emerging markets and pushes it into the same league as smaller emerging and frontier markets,” Emre Akcakmak of EastCapital (@akcakmak) wrote on September 12 in a tweet.

In the below, bne IntelliNews relays some of what Moody’s is saying.

Likelihood of BoP crisis

Turkey’s foreign currency reserves have been drifting downward for years on both a gross and a net basis but are now at a multi-decade low as a percentage of GDP because of the central bank’s unsuccessful attempts to defend the lira since the beginning of 2020.

Gross foreign exchange reserves (excluding gold, in line with Moody’s methodology) were at $44.9bn (as of September 4), marking a decline of more thatn 40% since the beginning of the year.

Turkey has tried a number of measures to increase gross reserves—including a tripling of the country’s swap line with Qatar to $15bn and increasing banks’ reserve requirements—but by any measure there is an exceptionally low buffer when measured against upcoming external debt payments.

Moody’s forecasts that the country’s external vulnerability indicator (EVI), an indicator of the adequacy of foreign currency reserves to cover external debt repayments and non-resident deposits, will rise from 263% in 2019 to 409% in 2021, which represents heightened exposure to changes in international investor sentiment.

In a crisis, the authorities could use the commercial banks’ reserves of $44bn deposited at the central bank to repay maturing external debt, which is why Moody’s uses gross reserves in its EVI calculation.

However, such a situation would increase the risk of the government imposing restrictions to safeguard its scarce FX assets.

In fact, if banks’ required reserves for Turkish lira and FX liabilities are netted out, net foreign-exchange reserves are now close to zero.

Moreover, the reliance on swaps has grown at a very rapid pace in 2020. As of the end of July, the Turkish central bank had a $53bn net short position in the swap market, up from $30bn in March.

In other words, all the commercial banks’ reserves at the central bank would be insufficient to cover this short position if these swaps were not rolled over.

Turkey does hold substantial gold reserves, and due to both increases in the gold price and an increase in gold volumes held, gold holdings are now broadly equal to FX reserves ($42.7bn at the beginning of September).

The lower the gross and net reserves go, the more likely it is that Turkey experiences a severe balance of payments crisis, causing acute disruptions to economic activity and further deterioration in the government’s balance sheet.

In the past, when the economy came under pressure, Turkey’s flexible exchange rate acted as a shock absorber that insulated the real economy from macroeconomic shocks and allowed the country to muddle through without addressing its structural imbalances. More recently, the authorities have been unwilling to allow the lira to float freely because of the economic consequences of a weaker currency.

Turkey’s weaker exchange rate does not have as much of an impact on growth and export competitiveness of goods as it does in many other countries because of the high import content of exports in some exporting industries.

That said, the tourism industry is highly responsive to a more competitive exchange rate, and periods of exchange rate weakness often coincide with tourist arrivals hitting record levels. This was certainly the case in 2019 when import compression and a very strong tourism season helped to shift Turkey’s current account deficit into surplus.

However, in light of the pandemic’s impact on the tourism industry, Turkey will not reap this benefit next year, and Moody’s base case is that globally the industry will only make a partial recovery to pre-pandemic levels in 2021.

Dollarisation is a significant issue for Turkey that heightens the risk of a balance of payments crisis; the Turkish economy has the second-highest dollarisation vulnerability indicator in the single B-rated universe. The country de-dollarised in the early 2000s because of growing confidence in the domestic economy. However, in recent years Moody’s has observed progressively higher levels of dollarisation, and since 2018 the share of deposits that are denominated in hard currencies such as USD or EUR have accounted for over 50% of the total deposits in the banking system.

Chart by @akcakmak.

Institutions

The second factor informing the rating action is Moody’s view that Turkey’s policy credibility and effectiveness, elements that the rating agency considers a governance factor under its ESG framework, have weakened.

At the moment, political pressures and limited central bank independence, a slow reaction function of the monetary authorities, and a lack of predictability in their reaction function increases the probability of a disorderly exchange rate and economic adjustment.

The policy rate is now negative in real terms, inflation remains well above target, and inflation expectations are rising. However, the central bank has taken only modest action to tighten monetary policy. The longer this goes on, the more likely it is that there will be continued downward pressure on the lira.

Moreover, Turkey’s longstanding commitment to a floating exchange rate since 2001 was an important institutional source of insulation from a balance of payments crisis because the exchange rate could act as a shock absorber. Given the scale and number of interventions and regulatory actions in the FX market this year, it is difficult to see the lira as being governed by a floating currency regime.

Turkey’s structural economic challenges are clear, and Moody’s believes that the Turkish authorities understand that the economy’s chronic shortfall in domestic savings generates significant imbalances and an over-dependence on foreign sources of capital.

Turkey also suffers from labour market rigidities that inhibit job creation. Productivity is also weak, which in some sectors underpins structurally high inflation.

International observers such as the EU, IMF, and OECD point to weak educational outcomes as a key driver of weak productivity and employment outcomes.

Policy initiatives in recent years have fallen short in terms of addressing the structural underpinnings of Turkey’s macroeconomic problems, pointing to a lack of willingness or capacity to tackle these economic vulnerabilities.

Moreover, growth-supporting measures have gone in the opposite direction and have relied on credit growth (and fiscal or quasi-fiscal stimulus).

Starting in the second half of 2019, state-owned banks were encouraged to expand credit creation to counter the economic downturn. They adopted special programmes to assume and restructure credit card and other consumer debt at extended maturities and below market rates. Credit growth has remained high in 2020 due to measures taken by the banking regulator to support domestic demand during the pandemic.

Some of those measures are being withdrawn now, but credit growth will remain high through the end of the year.

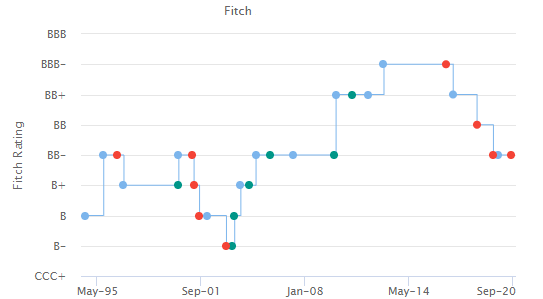

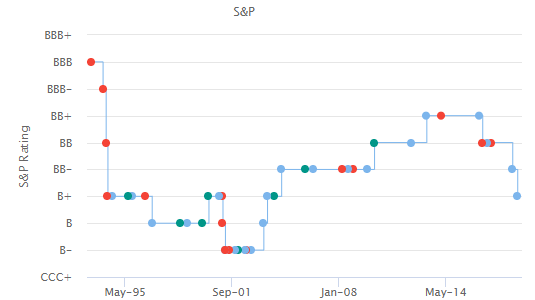

Chart by @e507.

The budget

Earlier this summer, Moody’s reduced Turkey’s fiscal strength factor score by two notches to “ba1” as debt affordability weakened markedly due to rising government debt levels, while there is a weaker debt structure that renders the government’s finances more vulnerable to high inflation and currency depreciation than was the case only a few years ago.

The fact that Turkey has had to contend with two crises since 2018 has taken a toll on the public finances even though the government’s fiscal response to the pandemic has been relatively modest.

The weak growth performance and fiscal measures to manage the economic effects of the coronavirus will have a meaningful impact on the deficit in 2020, and Moody’s forecasts that it will rise to 7.5% of GDP (using the IMF definition, which excludes one-off revenue sources).

In addition to the widening primary balance, the depreciation of the lira and high inflation will contribute to an increase in the debt burden and higher interest payments on account of an increased reliance on domestic and floating-rate borrowing which comes at the expense of higher yields.

As a result, Moody’s forecasts the government debt burden to increase from 32.5% in 2019 to 42.9% in 2020 and the debt affordability ratio (the ratio of general government interest payments to general government revenues) will deteriorate to 8.8% in 2020, up from 7.3% in 2019 and 5.8% in 2018.

Under Moody’s baseline scenario, the return to growth after the economic shock of 2020 will not suffice to offset the impact on the upward debt trajectory of primary deficits of around 2% and an increasing interest burden. Therefore, Moody’s expects Turkey’s debt burden to increase to above 46% of GDP in the coming years.

While Turkey’s debt metrics are still more favourable—sometimes by a significant margin—than those of similarly rated peers, in Moody’s view the deterioration in debt metrics outlined above means that Turkey’s fiscal strength no longer offsets the country’s other credit challenges to the same degree that it has in the past.

This situation could be exacerbated if, for example, the government’s desire to revive growth were to lead to even larger budget deficits than expected and if it needed to cover obligations on public-private partnerships (PPPs) or guaranteed debts.

Chart by @e507.

E(nvironmental) S(ocial) G(overnance)

Turkey experiences some environmental pressures because of rapid population growth, which has translated into industrialisation and rapid urbanisation. While this results in increased pollution and some degree of environmental degradation, these considerations are not material to Turkey’s credit profile.

Turkey is faced with labour market rigidities and low female participation rate in the labour market. Moody’s regards the coronavirus outbreak as a social risk.

Moody’s assessment of Turkey’s weak and deteriorating governance has been an important credit feature, which has underpinned its decision-making in downgrading Turkey’s rating by multiple notches since the introduction of the executive presidential system in mid-2018.

Since then it has become frequent practice in Turkey that official decrees, which order sometimes significant changes in laws and practice, no longer need go through parliament to gain approval. These interventions by decree have become more frequent since the 2018 market pressures. Moreover, the executive continues to undermine the independence of key institutions, meaningfully undermining those institutions’ credibility and effectiveness.

Default history: At least one default event (on bonds and/or loans) has been recorded since 1983.

Given the negative outlook, a positive outlook or an upgrade is highly unlikely. However, the rating outlook could stabilise if fiscal and monetary policies become more coherent in preventing further exposure to a balance of payment crisis near term. External financial support could also be credit supportive, as would diminished tensions with the US and the EU. A determined set of economic reforms that address the economy’s structural imbalances while capitalising on the country’s inherent strengths could lead to upward rating pressure over the medium term.

Turkey’s rating would likely be downgraded if there was an increasing likelihood that the current balance of payments pressures were going to deteriorate into a full-blown crisis. In such an event, the government could try to conserve scarce FX assets by imposing restrictions on foreign-currency outflows that affect sovereign creditors as well.

By: Akin Nazli

Source: bne IntelliNews