Cooperation must include adversaries, says energy expert Brenda Shaffer, doubting that either East Med gas pipe to Europe or big Israeli role in Europe-bound Gulf oil will take off

Sounds of celebrations coming from the Energy Ministry in the wake of this month’s normalization agreements with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, as well as Tuesday’s formal launch of the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), may be premature, experts say.

Israel currently has two functioning commercial gas fields — Tamar and Leviathan — with the smaller Karish and Tanin fields set to start production in 2021.

For the past three years, Israel and Egypt, co-founders of the EMGF, have been working hard to bring Jordan, Greece, Cyprus, Italy and the Palestinian Authority on board.

After all those parties signed on Tuesday, Israel’s Energy Ministry said in a statement that the forum would aid “development of the natural gas economy in Israel, and especially the export of natural gas from Israel to its neighbors, Europe and other regions.”

Israel’s Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz poses with a copy of the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) statute signed by Israel, Egypt, Jordan, Greece, Cyprus, Italy and the Palestinian Authority; on September 22, 2020. (Energy Ministry)

Israel sees the EMGF as a platform for advancing what Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz has in the past called a “very realistic” plan to lay an undersea pipeline that will carry natural gas from Israel, Cyprus, and Egypt to Italy, the gateway to Europe. It would be the longest and deepest underwater gas pipeline in the world. The EU has contributed 70 million euros ($81.5 million) for a feasibility study, which is being led by the Athens-based company, IGI Poseidon.

Poseidon said in April that it aimed to reach a FID (final investment decision) in two years. This is the stage where a company or conglomerate signals to investors that it has the money to implement a project and start a commercially profitable operation.

When work was starting on the EMGF, Steinitz declared that the then-estimated 6.2 billion euro ($7.36 billion) pipeline could take six to seven years to build and that the countries involved in the project were “serious about it, it will happen.”

In a separate development, the Globes business daily reported that following Israel’s normalization deals with the UAE and Bahrain, discussions within Israel’s Foreign Ministry and security circles have gathered pace over the possibility of offering the Gulf a land bridge between Saudi Arabia and European oil markets — using an old pipe that connects the Red Sea (at Eilat) with the Mediterranean (at Ashkelon).

But according to Brenda Shaffer, an international energy expert at Georgetown University, the East Med pipeline is unlikely to be realized and the land bridge idea may be implemented, but only for emergency use.

International energy expert Brenda Shaffer (Courtesy)

“Currently, commercial prospects for this proposed [EMGF] pipeline are very low,” she told the Times of Israel from Washington DC. “There is not one company that’s committed to this project. Companies in general don’t like to invest in pipelines, because they mean a lot of risk and not a great return. And Italy is not on board.”

Italy, she continued, gets gas from Russia, Central Europe and Algeria, and is currently carrying out testing for the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), which will transport gas from Azerbaijan’s massive Shah Deniz gas field to Europe. TAP will channel gas to Europe from Azerbaijan via Greece and Italy. “Italy is not committed to the [EMGF] pipeline anymore and it’s the only important market along that route,” Shaffer said.

In a lucid analysis published last month, Sir Michael Leigh, whose expertise includes Europe, energy, Turkey, the Mediterranean and the Middle East, said that while gas reserves discovered by Israel and Cyprus are valuable to the countries themselves, they are “insignificant in terms of international energy markets.”

Sir Michael Leigh. (YouTube screenshot)

He wrote, “The attractive notion of a pipeline from the region to Europe, agreed in principle by the governments of Cyprus, Greece and Israel, faces technical and financial obstacles and will not happen unless considerable additional quantities are discovered.”

Cyprus, he added, is importing gas because it lacks the infrastructure to exploit its own reserves, while Greece has so far made no commercially significant offshore gas discoveries.

A land bridge for Gulf oil to Europe?

The Globes newspaper last week reported on discussions within the Foreign Ministry involving senior officials from the state-owned Europe-Asia Pipeline Company (EAPC) about the possibility of providing a land bridge for Gulf countries to transport their oil, gas and fuel distillates to Europe.

View of the Europe-Asia Pipeline Company after an oil leak in the Arava area of southern Israel caused the country’s biggest environmental disaster, December 9, 2014. (Marc Israel Sellem/Jerusalem Post/POOL)

The oil would go from Abkeik in eastern Saudi Arabia (which has not yet signed any agreements with Israel) via an existing pipe to Yanbu on its western coast. A 700-kilometer (435-mile) overland pipe would be built to connect into Israel’s southernmost port of Eilat, on the Red Sea. From there, the oil would be taken — via the existing state-owned Europe Asia Pipeline Company — to Ashkelon on the Mediterranean coast for departure by ship to Europe and North America.

Globes pointed out that the peace agreement signed by Israel and the United Arab Emirates includes the clause, “the sides will advance and develop cooperation in projects in the area of energy including regional transport systems to increase energy security.”

Today, Saudi Arabia only supplies around six percent of the EU’s oil.

‘Not commercially viable’

Shaffer — a former energy policy adviser to the Israeli Prime Minister’s Office and Energy Ministry, who currently serves as a faculty member of the US Naval Post-Graduate School, a senior adviser for energy at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies think tank in Washington, DC, and a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center — doubts this vision will get off the ground either.

The Shah of Iran Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and wife Empress Farah Pahlavi of Iran during a visit to Aswan, Egypt in 1979. (AP Photo/Bill Foley)

“When this pipeline was built [before the shah of Iran was ousted by the current Islamic regime], the idea was to bring Iranian oil to markets in Europe and at that time it made sense,” she said. “Europe was an importing market. The Soviet Union was exporting far less oil than Russia does now. Today, Russia supplies most of Europe’s oil, together with Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan.

“The Gulf exports mainly to Asia. So if it is to be used at all, I think this pipe line would serve only in an emergency, for example if Iran blocked the Persian Gulf. But it doesn’t make sense on a daily commercial basis. It would make the oil too expensive. It could be a boutique pipeline.”

She added, “There isn’t a lot of oil from the Gulf to Europe – and tankers are still cheaper and safer than pipelines, so if you can go by tanker [from the Red Sea], you’ll do that instead.”

Illustrative photo of a Saudi Arabian oil facility. (Shutterstock images)

Going back to Tuesday’s official launch of the East Mediterranean Gas Forum, Shaffer said it was a “huge mistake” not to invite Turkey.

“There’s no meaning to regional cooperation if you don’t include adversaries,” she opined. “It’s exacerbated the situation with Turkey, which sees the forum as anti-Turkish. [Ankara has already called it an “alliance of malice.”] Imagine that everyone was invited other than Israel. Israel would see this as anti-Israeli. The forum has neither money nor troops.

“Its establishment has raised tensions in the region. Turkey is still a very important power. Israel’s relations with Greece and Turkey should not be a zero sum game.”

A backdrop of escalating Greek-Turkish rivalry

The official launch of the EMGF took place against the backdrop of an escalating Greek-Turkish power struggle in the Eastern Mediterranean, which Germany has warned could spark a war.

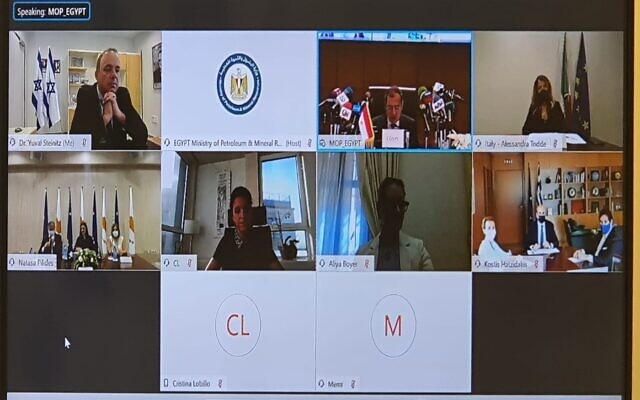

A screenshot of an online ceremony during which Israel, Egypt, Jordan, Greece, Cyprus, Italy and the Palestinian Authority formally signed the statute of the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), to be based in Cairo, September 22, 2020. (Energy Ministry)

Israel, whose relations with Islamist Ankara have long been in decline, has joined the European Union and the US in taking Greece and Cyprus’s side. Shaffer thinks that Israel, France, and the UAE should “sit this one out and let Washington resolve this with Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey.” Moscow, she says, is doing what it can to fan the flames and take Turkey away from NATO — something that would not only deal a victory to Russia but be a “huge loss for the US and NATO,” given that Turkey is a large and powerful state that borders Russia and the Black Sea.

Greek-Turkish enmity is currently focused on maritime drilling rights, but reflects a much wider, bilateral rift that has flared on and off since the 19th century, only to be strengthened by Turkey’s invasion of northern Cyprus in 1974.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan after a cabinet meeting at the Presidential Complex in Ankara on August 10, 2020. (Adem ALTAN/AFP)

Turkey has a 1,600-kilometer (just under 1,000-mile) long Mediterranean coastline. But together with Israel and a handful of other nations, it has not signed the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The convention gives signatories — which include Greece and Cyprus — the right to establish offshore Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). Turkey claims that its national rights override this treaty. Shaffer says that the law on maritime delimitations is “very murky.”

In November, Turkey signed an accord with Libya on the “delimitation of maritime jurisdictions,” with Greece angrily pointing out that Crete lay between these two countries.

In this photo provided by the Turkish Defense Ministry, Turkey’s research vessel, Oruc Reis, in red and white, is seen surrounded by Turkish navy vessels as it heads to the west of Antalya on the Mediterranean, Aug 10, 2020. (Turkish Defense Ministry via AP, Pool)

Last month, Ankara upped the ante by sending a vessel, accompanied by warships, to survey for oil and gas in waters claimed by Greece. At one point, according to Reuters, Greek and Turkish warships collided.

Egypt and Greece struck back, signing their own maritime-boundary agreement. The Egyptians want to curb Turkey’s influence in the Eastern Mediterranean and have little in common with Ankara following the 2013 ouster of Mohamed Morsi’s Islamist regime.

‘Any spark could lead to disaster’

Calling for a de-escalation of tensions last month, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas warned, “The current situation in the Eastern Mediterranean is … playing with fire, and any spark, however small, could lead to a disaster.”

German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Jerusalem on June 10, 2020. (Olivier Fitoussi/Flash90)

Germany, home to a large Turkish population and keenly aware of Turkey’s role as a buffer against refugees and migrants, currently holds the EU presidency. EU ministers have reaffirmed full solidarity with Greece and Cyprus, but called for an approach based on “solidarity, de-escalation, and dialogue.”

France, on the hand, is taking an aggressive anti-Turkish stance. Last month, the French joined military exercises with Greece, Cyprus and Italy, just off southern Cyprus. The French have also asked to join Israel and Egypt’s new regional forum, in which the EU and the US are observers.

French President Emmanuel Macron, wearing a face mask at the Elysee Palace in Paris, on August 26, 2020. (Ludovic Marin / AFP)

This tough, partisan position, wrote Michael Leigh, could undermine the EU’s efforts to prevent a conflagration.

Leigh, a senior fellow at the European economics think tank Bruegel and an adjunct professor at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University in Bologna, suggests that Turkey’s recent discovery of large gas deposits in the Black Sea could be a “game changer,” limiting Ankara’s eagerness to find gas in the Eastern Mediterranean and opening a window for talks with Greece.

Turkey’s drilling ship, Fatih, heads toward the Black Sea in this May 29, 2020, photo, with the Hagia Sophia in the background, in Istanbul. (AP Photo/Emrah Gurel)

“But mediation will only stand a chance if there are convincing incentives for both parties,” he continues. “For example, the EU could double down on its rejection of any resort to force by Turkey and, at the same time, press for Turkish participation in the Eastern Mediterranean Energy Forum.”

By: Sue Surkes

Source: The Times of Israel