The Turkish president’s son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, brought his operative back from the shadows to run front company Powertrans, which has long been accused of transporting illicit oil from areas administered by the local Kurdistan government as well the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), when the jihadist group controlled oilfields.

Ahmet Muhassıloğlu, a caretaker for Albayrak who designed a sophisticated scheme involving Singapore and the British Virgin Islands, returned to take over the Powertrans in 2019 after laying low for six years. According to the trade registry records, Muhassıloğlu, who left the firm after its launch returned to the company in December 2017 and became chairman of the board in August 2019.

The reappearance of Muhassıloğlu suggested that Albayrak and his father-in-law, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, felt confident enough in their quest of further consolidate their power after a massive purge of senior government officials from the judiciary, military, intelligence and police in 2016 and 2017. With no checks on their activities by those entities and no oversight by regulatory bodies, Albayrak apparently decided to play his hand openly with no fear of running afoul of the authorities in his illegal schemes.

Muhassıloğlu was a representative for the Turkish Islamic Kuveyt Turk bank in Germany and ran the bank’s Munich branch in 2004. He was later hired by the Çalık Group, a major Turkish conglomerate that has interests in energy, construction, media and other sectors. Çalık grew rapidly with the government’s backing while Albayrak was the CEO of the group until December 31, 2013.

Before his departure from Çalık and becoming energy minister in his father-in-law’s cabinet, Albayrak laid the groundwork for Powertrans with people handpicked from Çalık. Muhassıloğlu had been in charge of the group’s Turkmenistan operations in the past, acquiring international experience in getting Powertrans off the ground.

The leaked emails of Albayrak in 2016, captured by leftist hacker group RedHack, revealed how Erdoğan’s son-in-law was micromanaging the operations of Powertrans and deciding on small matters, from food rations provided to the company’s employees in the field and travel expenses to the responsibilities tasked to managers. While he was privately involved every step of the way, Albayrak publicly lied that he had nothing to do with the firm and threatened those who wrote about Powertrans with legal action.

Muhassıloğlu was one of the main partners in Powertrans, holding a 50 percent share when it was first established on March 25, 2011 in Istanbul with start-up capital of 50,000 Turkish lira ($32,150), according to trade registry data. The other partner was listed as Grand Fortune Ventures Pte. Ltd., a Singapore-based shell company. A month later, Muhassıloğlu suddenly decided to sell his shares to another Singapore-based shell company, Lucky Ventures Pte. Ltd., but continued to run the firm as general manager. Both ventures, originally established in 2008 in Singapore, were moved to the British Virgin Islands a year later, suggesting that they were parked there for some time to be used in such illicit schemes as profit enhancement and tax evasion.

The company was left idle for four months until then-Prime Minister and now President Erdoğan secured a cabinet decision No.2011/2033 on July 18, 2011 that required licensing for the transport of crude oil and jet fuel through Turkey by truck and train. The eight-point cabinet ruling authorized the Ministry of Customs and Trade, led by Erdoğan’s long-time ally Hayati Yazıcı, to issue licensing of the oil transfers from a foreign country to Turkey and from Turkey to another foreign country.

Soon after, the Customs Ministry gave Powertrans exclusive rights to carry oil from Iraq, which the government publicly acknowledged in 2015.

More activity was recorded in Powertrans after the cabinet decision, which effectively handed a lucrative business venture with no competition to a brand new company that had no experience and no record in the oil business. At a board meeting on December 21, 2011, the firm’s capital was increased to 10 million ($5.3 million). Cheung Chi Ho and Young Ngiat Sim attended the meeting as representatives of Grand Ventures, and Andrew Gordon Galway and Young Ngiat Sim on behalf of Lucky Ventures. Both venture firms held a 50 percent stake in each.

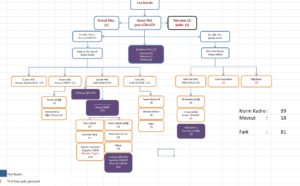

In 2012 Muhassıloğlu moved into the shadows, leaving the company to other caretakers who ran Powertrans on behalf of Albayrak and Erdoğan. On June 4, 2012 Ahmet Şadi Güngör, who previously worked in the petroleum trade coordination department of the Çalık Group, became general manager of Powertrans. Güngör had run unsuccessfully as a nominee on the Justice and Development Party (AKP) ticket in 2007 and 2015, and his wife Nurten Güngör had been active in the AKP’s women’s branches in Kocaeli province. Şevket Acar, also a Çalık employee, became chief financial officer at Powertrans.

The organizational chart, planned in September 2012, envisaged that Powertrans would specifically focus on Iraq. Each and every step was submitted to Albayrak for his approval, although he had no official responsibilities at Powertrans. The leaked emails showed that he even decided how much lunch and travel money would be provided to company employees.

By that time, it was clear that the company was expanding, bringing more hands on deck. Dursun Ali İşgüzar was running point at the Tawke, Shaikan and Doha oil fields from Powertrans’ office in Erbil. Salih Güner was responsible for logistics, facilitating truck movements through the Habur gate on the Turkish-Iraqi border and assisting in the shipment of oil from Turkish ports in Ceyhan, Dörtyol and Mersin on the Mediterranean.

Everything was in place before the Kurdistan Regional Government’s (KRG) move in October 2012 to sell its oil in the international market in independent export deals in defiance of Baghdad. Erdoğan helped the KRG use Turkish territory to do this business in exchange for the KRG favoring Powertrans. It was a pure abuse of power by Erdoğan to enrich his family through illicit and backroom deals.

Powertrans initially moved small shipments of oil from Iraqi Kurdistan to test the waters. Trafigura, one of the world’s largest trading houses, was the first to take the Kurdish oil cargo worth more than $10 million in a deal brokered by Powertrans as intermediary. The Kurdish oil was trucked to Turkey and then shipped from Turkish ports on the Mediterranean. Another $10 million oil purchase in the same month was made by Vitol, another major trading house that picked up the oil from Turkey’s Toros terminal.

Baghdad was not happy, however. The Iraqi federal government was furious at the KRG’s move and complained about Turkey’s facilitation of the Kurdish oil sales, describing it as stealing from Iraq’s treasury. The Erdoğan government paid no attention to the criticism, while the family enterprise pocketed substantial revenue from the Kurdish oil sales. The small volume sales accelerated, with the KRG planning to move more crude to Turkey via a new pipeline to later be built. In January 2013 Powertrans brokered a 30,000 ton cargo from the KRG’s Shaikan oilfield. The oil was trucked to the Turkish port at Dörtyol on the Mediterranean.

With its prospects looking promising, Powertrans decided to expand further. It changed its status on April 22, 2013 from a limited company to joint stock company, which allowed more room for Powertrans to operate and grow further. Güngör became CEO and Acar his deputy.

In 2013 Albayrak brought in his cousin, Ekrem Keleş, to run Powertrans’ sales and marketing department and made Acar the CEO. Two new people were brought aboard at a meeting on April 25, 2013: Cem Osman Sokullu as deputy general manger, and Ayhan Saraç as coordinator of financial affairs. Two Turkish nationals, Muhsin M. Nezir and Amen Işıl Gözleveli, were named as holders of B-group shares.

The restructuring of Powertrans came amid a huge spike in the company’s revenue, reportedly $674 million as of July 31, 2013. The company was also poised to benefit immensely from multi-billion dollar energy deals including gas pipelines and exploration opportunities, signed by the Erdoğan government and the KRG on December 29, 2013. The agreements, valid for 50 years, regulate the delivery of Kurdish oil and gas to the Ceyhan district of Adana, products that would then be sold on the international market. The Iraqi federal government was furious, accusing Turkey of “interfering in the sovereign rights of Iraq.” Erdoğan defied Baghdad and added more deals with the KRG in March 2014.

In July 2014 the KRG oil sales were brought to parliament’s agenda with a question posed to then-Energy Minister Taner Yıldız to explain the details of the agreements. The ministry declined to provide details, claiming that the Iraqi side had contracts with private companies on the Turkish side and that the government had no role in that.

In the meantime, more allegations surfaced about Powertrans with regard to ISIS oil. It was reported that some of the oil transported by Powertrans did not make it to the port for re-export but rather was illegally sold to the domestic Turkish market. The allegations were investigated by Customs and Commerce Ministry inspectors, but it was eventually hushed up. The allegations that Powertrans was involved in the smuggling of ISIS oil from Syria were also not investigated under pressure from the Erdoğan government.

It was widely reported at the time that Erdoğan’s son Bilal Erdoğan and Maltese shipping company BMZ (derived from the initials of its three partners: President Erdoğan’s son Bilal, his brother Mustafa Erdoğan and his sister’s husband Ziya İlgen) were involved in ISIS’s oil trade. The main accusation, initially raised by the Russian government, was that Powertrans was transporting Kurdish oil commingled with crude from ISIS-controlled wells to Ceyhan, from where Bilal’s ships were delivering it to international markets.

The US government also provided some clues as to where the ISIS oil went. US Department of the Treasury Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence David S. Cohen said that ”ISIS was selling oil at substantially discounted prices to a variety of middlemen, including some from Turkey, who then transported the oil to be resold. It also appears that some of the oil emanating from territory where ISIL operates has been sold to Kurds in Iraq, and then resold into Turkey.”

Powertrans attracted new attention on May 23, 2014, when the Iraqi government officially complained to the International Chamber of Commerce about Turkey, listing the names of the local and foreign companies selling Kurdish oil illegally in the international market.

As of January 2015, 34 million barrels of oil had been sold by the KRG, valued at $2.5 billion. The oil extraction capacity of the Kurdistan region also rose to 400,000 barrels per day in January, with 150,000 of those barrels sold in the domestic market. The remainder was transported through the Ceyhan pipeline in line with an agreement signed with Baghdad.

In October 2015 Keleş left Powertrans, followed by Gözleveli in December 2015 and Okullu in October 2016. At a board meeting held on December 21, 2017 Muhassıloğlu, who had set up Powertrans, returned and assumed the chairmanship on August 8, 2019. According to the leaked emails, Albayrak continued to be involved Powertrans dealings in Iraq while he served as energy minister. Albayrak left the energy ministry to a caretaker and assumed the position of finance and treasury minister in a July 2018 cabinet reshuffle.

The leaked emails also confirmed that President Erdoğan’s lawyer, Ahmet Özel, also handled legal matters in Powertrans dealings on behalf of Albayrak. When an article appeared in the Turkish press in March 2015 about Powertrans, alleging government favors and Albayrak’s links to the company, Özel drafted a legal notice to the newspaper denying the allegations. Özel is partners with another lawyer, Mustafa Doğan İnal, who also works closely with Erdoğan. İnal also communicated with Albayrak on Powertrans matters. İnal represented controversial Saudi businessman Yasin Al-Qadi, a close friend of Erdoğan who for years was listed as an al-Qaeda financier by both the UN Security Council sanction committee and the US Treasury.

Albayrak abruptly resigned in November 2020 as finance minister amid an overhaul of the economic leadership. Some alleged that a feud within the family led to his sudden departure, but months later Erdoğan started defending his son-in-law’s track record, fueling speculation that he might return to the government or to AKP management. From the shadows, he still manages the family’s business ventures including Powertrans and is considered to be a highly valuable asset in moving and protecting the Erdoğan family wealth in Turkey and abroad.

By: Abdullah Bozkurt

Source: Nordic Monitor