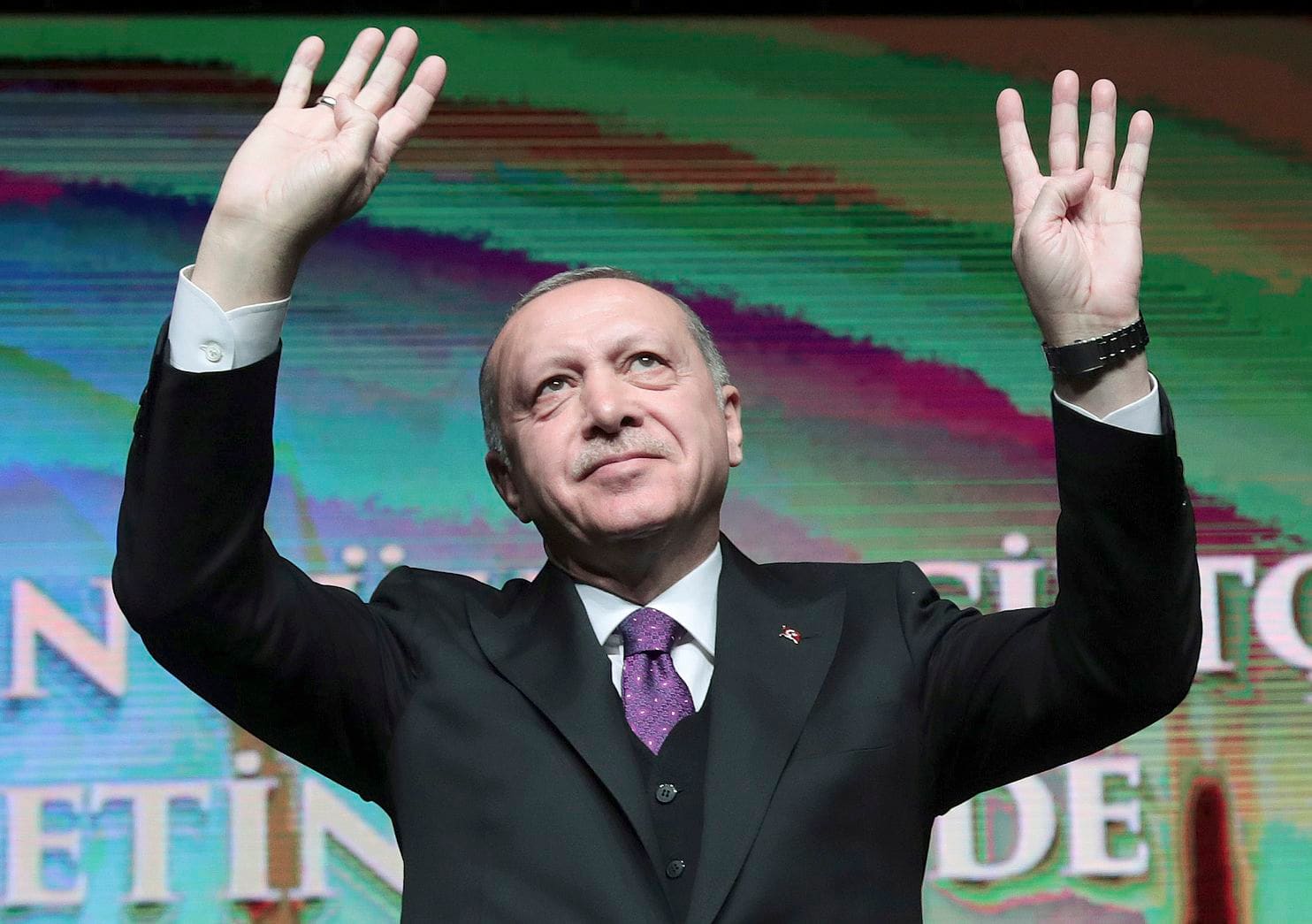

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan waves to supporters following his speech at an event in Ankara, Turkey, on March 6. (Presidential Press Service via AP)

For a scary snapshot of what a “post-American” world looks like, consider the rupture that has been developing through three administrations in the U.S.-Turkey relationship. Turkey has come to think it can call the shots, regardless of U.S. interests.

The prime mover has been President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Over the past decade, he has altered Turkey’s political geography — undoing the Western-facing secular republic created by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and creating a neo-Ottoman Turkey that’s more aligned with its eastern neighbors, including Russia.

“Ever since the end of the Cold War, this relationship has been in trouble, because the common threat of the Soviet Union has disappeared,” argues Bulent Aliriza, who heads the Turkey Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. U.S. presidents have tried to coerce and cajole Erdogan, but to little effect.

The two countries are now heading toward the most serious confrontation yet. The Pentagon warned Monday that Turkey would face “grave consequences” if it went ahead with its planned purchase of a Russian S-400 air-defense system rather than the Patriot system the United States has offered. NATO commander Gen. Curtis Scaparrotti on Tuesday implored Ankara to “reconsider.”

Erdogan responded, in effect, by flipping the bird. “It’s done,” Erdogan said Wednesday of the S-400 purchase. “There can never be a turning back. This would not be ethical, it would be immoral. Nobody should ask us to lick up what we spat.”

Erdogan’s defiant decision comes despite U.S. warnings that Turkey was jeopardizing its role as a partner in building the F-35 fighter — the very weapon the S-400 is designed to shoot down. Having the rival weapons systems in the same country could compromise the security of the F-35, U.S. officials believe. They are now scrambling with Lockheed Martin, the lead contractor, to find alternative sources for fuselage parts and hundreds of other F-35 components that were to be made in Turkey.

“We have to take them [the Turkish government] at their word,” says a senior Trump administration official. “We have a responsibility on our side to take the steps that are necessary.”

“Turkey is a totally unreliable ally,” argues Eric Edelman, who served as U.S. ambassador to Ankara from 2003 to 2005. Edelman was warning about Erdogan’s “authoritarian loner streak” back then, in a January 2004 cable revealed by WikiLeaks: “Erdogan has traits which render him seriously vulnerable to miscalculating the political dynamic, especially in foreign affairs.”

The Turkish pendulum has been swinging away from the West, despite attempts by the past three U.S. presidents to reassure the Turkish leader. Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama both pushed Europe to admit Turkey into the European Union; Obama treated Erdogan as a model Muslim leader during the Arab Spring, courting the Turkish leader in more than 20 personal phone calls. President Trump embraced Erdogan as a kindred spirit and offered in December to withdraw U.S. troops from northeast Syria and let Turkish forces take over there, a position he has since reversed.

The United States and the NATO alliance are strong enough to survive Erdogan’s mischief. The tragedy is that the Turkish leader has been sabotaging his own country’s progress, which had been one of the world’s great success stories. Erdogan crushed a thriving free press, enfeebled a once-strong military, jailed thousands of dissidents and undermined the Turkish economy, once the jewel of the emerging markets.

Erdogan’s version of populist nationalism features strident attacks on the Kurdish Workers Party, or PKK, that approaches Kurdophobia. A decade ago he was exploring a possible truce with PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan; now he blasts the group and its Syrian Kurdish affiliate, the YPG, as terrorist organizations — even though the YPG has been America’s best ally against the Islamic State. This anti-PKK zealotry moved a step further this week, when Turkey’s interior minister said Turkey and Iran were planning joint operations against the group.

There has been a string of anti-American moves by Erdogan in recent years: undermining U.S. sanctions against Iran; jailing pastor Andrew Brunson; blaming the United States for the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey; allowing his bodyguards to attack demonstrators in Washington in 2017; and touting Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro in a January phone call, saying, “Maduro brother, stand tall, Turkey stands with you,” according to a tweet by Erdogan’s spokesman, Ibrahim Kalin.

In today’s messy world, the United States seems to be everyone’s target, and authoritarian leaders take potshots at will. And for now, sadly, Erdogan is a wrecking ball for Turkish efforts to build a modern, Western-style democracy. But eventually, the political pendulum swings back.

Source: Washington Post