By Cagan Koc

It’s payback time for Turkey’s economy after a decade of living beyond its means, and the reckoning couldn’t come at a worse time for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan as the country heads toward bellwether municipal elections.

An era of record monetary stimulus around the world supercharged Turkish companies as capital came pouring in, more than doubling corporate credit in the past 10 years. Driven by Erdogan’s push for growth at all costs, the momentum rarely stalled as the Middle East’s biggest economy repeatedly boomed back to life after downturns.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan

Photographer: Arif Akdogan/Bloomberg

But an almost uninterrupted expansion that lifted the economy by an average of nearly 7 percent each quarter since late 2009 is now giving way to recession following a currency crash, policy missteps and an unprecedented diplomatic rift with the U.S.

Data due Monday will probably show gross domestic product ended last year with two consecutive quarters of contraction. On a seasonally adjusted basis, the pace of decline worsened to 2.4 percent during the last three months of the year from the previous quarter, when GDP shrank 1.1 percent, according to economists polled by Bloomberg. From a year earlier, it dropped 2.5 percent in the fourth quarter, another survey showed.

For investors, the worry is that Turkey will face a long slog to recovery as the torrent of foreign capital dries up while households and companies begin paying down debts.

“Unlike Turkey’s past V-shaped recoveries, there’s the significant risk that the recovery will be much slower this time round,” said Inan Demir, an economist at Nomura International Plc in London. “The entire Turkish economy may be facing deleveraging pressures.”

The undoing of Turkey’s growth model comes at a sensitive time for Erdogan, who first became prime minister in 2003, as he braces for his first test at the ballot box since assuming vastly expanded executive powers last year. After the March 31 vote, Turkey isn’t scheduled to hold another election for four years.

In an effort to restart growth, the government has heaped pressure on state banks to ramp up credit, helping annualized lending turn positive last month for the first time since August. It recapitalized three of its lenders by selling bonds to Turkey’s unemployment fund, and is working on a fresh plan to further bolster state-owned banks’ capital.

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say

“Turkey’s economy probably entered a technical recession in the fourth quarter of last year. Timely indicators, such as industrial production, banking credit and the PMI manufacturing survey, show the economy likely contracted for a second consecutive quarter.”

–Ziad Daoud, Mideast economist

Click here to view the piece.

For now, the outlook remains bleak. GDP may be in contraction through the first half of 2019, followed by four quarters of tepid growth that will average less than 3 percent from a year earlier, according to Bloomberg polls.

As the central bank holds interest rates high to stabilize the lira and keep inflation in check, the engine of Turkey’s economy is misfiring. Real banking credit shrank by 7.2 percent on a quarterly basis in the last three months of 2018.

With total debt at 121 percent of GDP, the ratio of non-performing loans may climb to about 7 percent this year from around 4 percent, according to a February report by Morgan Stanley, which cited the guidance it received from lenders. The World Bank in December put the share of what it called “distressed assets” at closer to 13 percent.

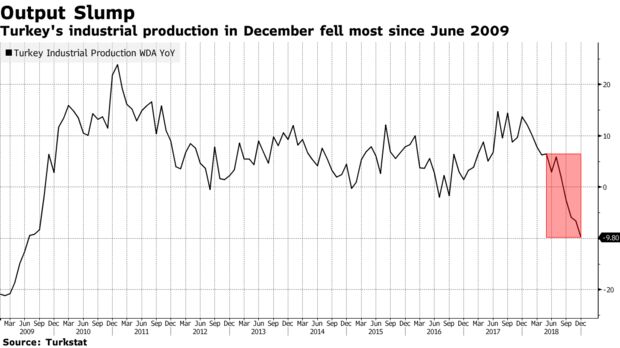

Industrial production capped 2018 with its biggest plunge in more than nine years, while economic confidence languishes near the lowest level since the 2009 crisis. Turkey’s largest companies have either completed or sought almost $24 billion of loan restructurings.

“We expect a recovery, but slower than in the earlier episodes,” said Magdalena Polan, emerging-markets economist at Legal & General Investment Management. “ Fortunately for Turkey, potential growth is high.”

— With assistance by Harumi Ichikura, Kyungjin Yoo, and Constantine Courcoulas

Source: Bloomberg