Local elections on March 31 have critical implications for Turkey’s transition to the new executive presidency that came into force after general elections last year.

Political parties on all sides, including President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), agree on the importance of these elections. Political parties are rooted in identity politics, but will interpret victory as a plebiscite on their policies.

If the AKP comes out on top, the president will inevitably construe the results as a blank cheque to continue his policies. On the other hand, if the results favour the loose coalition that has formed to oppose the AKP and its far-right allies, it will not change the trajectory of politics.

Beyond the two blocs, there is a third entity in these elections, the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), the first pro-Kurdish party to overcome the 10-percent electoral threshold and enter parliament in 2015. The HDP’s leaders, a number of its members of parliament and many of its members have been jailed on terrorism charges. In spite of the legitimate support it has received in numerous elections, the HDP has been shunned in domestic politics, alienated and criminalised, and regardless of how many votes the party receives, it is difficult to envision a democratic detente towards the HDP after the March 31 polls.

The election campaigns have not made space for debates about local governance and voter demands, other than heroic pledges and hackneyed populist rhetoric, but have instead been dominated by threats and aggression. This should be expected; in terms of governance, Turkey is undergoing the most critical period in its history

The instruments of the state, including the judicial system, the control of institutions, and the balance of power are arranged to benefit the AKP coalition. The government has in the past five years firmly established a clientelist structure, a centralised and partisan system that is alone enough to inhibit a fair election.

The constitutional order has in practice been suspended. The executive presidency was sold to the electorate as a means of strengthening and updating the constitutional foundations of the country, but was voted in through elections mired in allegations of fraud. Since it does not rest on a social consensus or a majority accord, there is no longer a social contract left to bind the country together. The constitution further centralises an already centralised system and has the potential to push society over the edge

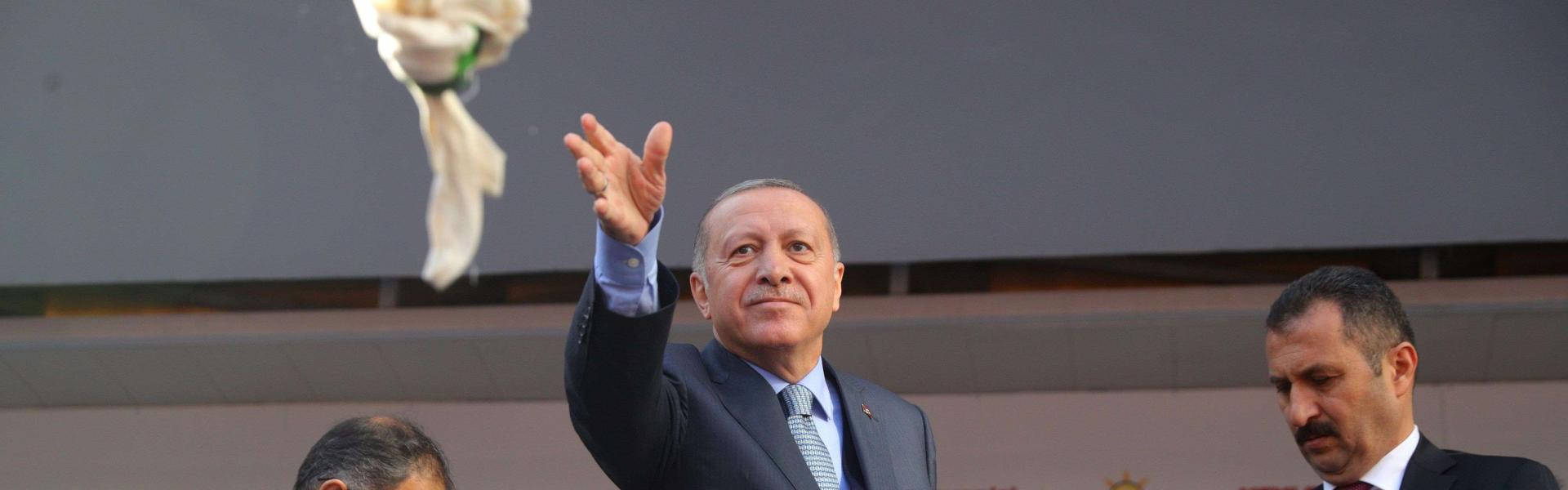

Although the presidency is meant to be an office above politics, Erdoğan has again become the leader of the AKP and trampled on the constitution and political conventions by personally going on the local campaign trail, all with little objection. Erdoğan has crossed many red lines, exploiting religion and ethnicity to an extent that surpasses his predecessors and his belligerent rhetoric has been normalised.

The result is that

Turkey is left with no guarantees of universal rights.

Always known for being politicised, the judiciary is now fully dependent on the executive. Laws are enforced at the whim and request of the regime, or not enforced at all. Before, the AKP at least went through the pretence of passing laws to uphold the guise of legality, but even this charade has now been lifted. The president and his ministers now openly use hate-filled rhetoric and hurl threats against elected officials, without any legal repercussions

This is an important development. It leaves no doubt about how those in power view the new system of administration.

One could say that after March 31, regardless of the election results, an open-ended, limitless model of authoritarianism will grow and get stronger.

In addition to the independence of the judiciary, the president has targeted the autonomy of key state institutions. The influence of parliament has been limited, and it is now a mere forum where highly paid opposition parliamentarians simply make suggestions. Checks and balances have collapsed.

Bear in mind, the powers entrusted to the executive affect local municipalities as much as they do parliament. Even if they win the elections, opposition-run municipal governments can only function with the approval of the central governing party. The HDP is certain to win some municipal elections in the Kurdish southeast, but the central government will replace its elected mayors with administrators

Another factor that tips these elections in favour of the governing coalition is the media. In violation of its own bylaws, state broadcaster TRT has become almost entirely an AKP mouthpiece, and the private media, also almost fully under government control, has similarly discounted opposition parties, especially the HDP.

Deep disappointment and anger against the system will undoubtedly emerge.

In that case, are there any solutions?

Under these conditions, in a Turkey devoid of justice and governed by a mantra of remaining loyal to the government at all costs, the only effective opposition is the economy. Unfortunately, the signs are of a severe economic downturn after March 31. This will pressure not only the governing coalition, but also the opposition.

Due to manipulative and untrustworthy polls, there seems to be growing hope among the opposition, just as in the last elections. We believe the appropriate attitude is pragmatism. It should not be forgotten that in the current climate of extrajudiciality, it would be very difficult for opposition parties to turn municipal electoral victories into effective local government.

Within this framework, we believe that speculating on scenarios of snap elections based on dubious polling is tantamount to counting your chickens before they are hatched. First of all, a parliament only last year will not easily call for snap elections. Secondly, even if the AKP’s far right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) allies call for snap elections due to economic pressures, the executive will turn to other nationalist parties to secure a coalition. For Ahval, these two scenarios are enough to indicate the severity of Turkey’s systemic crisis.

The crisis will produce its own opportunities. In the case of Turkey, it seems that new “civil solutions” and opportunities to return to democracy will require a worsening of the ongoing crisis. Society will either bow down, or find an exit path towards compromise.