The Armenian Genocide is Turkey’s founding evil. Is it possible for a system that was founded on this atrocity – the liquidation of the non-Muslim citizens of the Ottoman Empire – to work properly? How can this huge loss determine Turkey’s situation today?

Here are a few examples, from many thousands, of the political and social cornerstones of the system that fosters a culture of denying equal citizenship, extortion, denying responsibility, and accountability, impunity, and making people forget the past and instead memorise the official narrative.

Regarding equal citizenship, the approach today is no different than what it was at the beginning of the 20th century. Both of them reveal a determination to jealously refuse to share power.

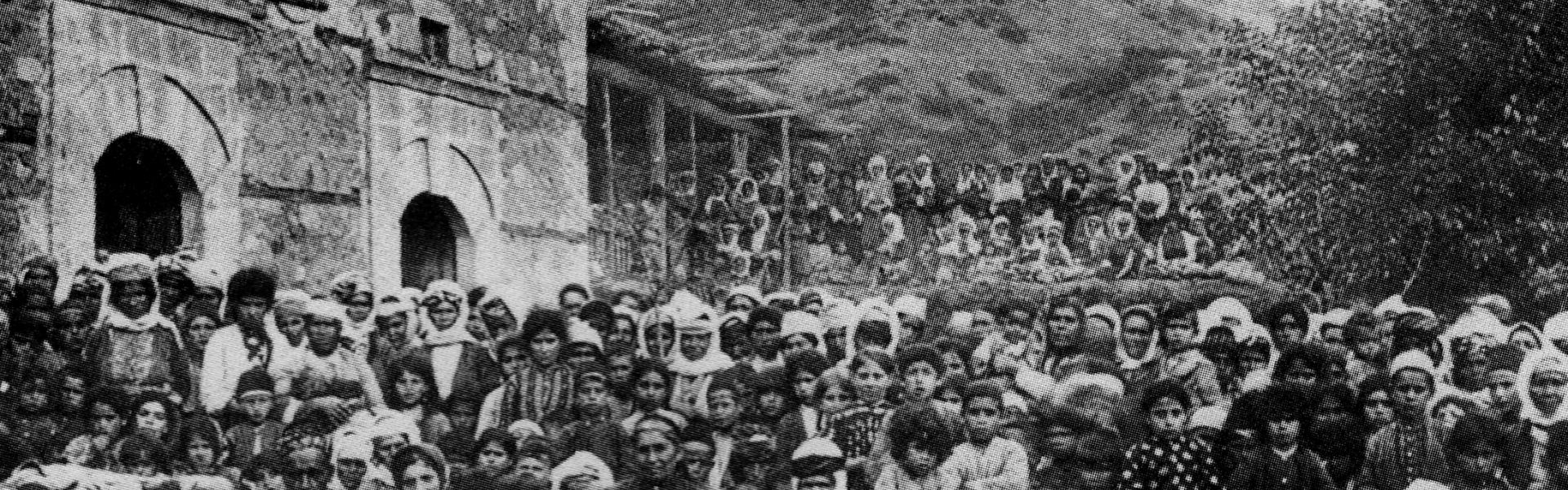

Would non-Muslims be equal to Muslims in the new Turkish nation being established after the fall of the Ottoman Empire? They were not and non-Muslims were no longer able to live on the lands where they had been for centuries.

Today the question is whether Kurds will be accepted as equal to Turks. There is no clear answer, but the trajectory of what has happened since the founding of the republic in 1923 suggests they will not.

Even what has happened since the March 31 local elections is evidence of this. The tactical support given by the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) to other opposition parties in the polls was a one-way Kurdish overture to Turks that helped fiercely anti-Kurdish opposition parties win municipal seats in the west of the country.

On the one hand there is the cheerfulness in the west at the election of the opposition’s Ekrem İmamoğlu as Istanbul’s new mayor, but a deaf ear towards Kurdish allegations of electoral fraud in the east.

The inequality between those in power and the second and third class citizens has determined the social vision since the 19th century Tanzimat reforms and reached its peak in the Armenian genocide.

The culture of extortion/spoliation is closely tied to that inequality and springs from the right of conquest that says Muslims have the right to seize the property of heretics. This mentality never apologises, but makes others apologise. Almost all the property of non-Muslims has been expropriated, despite hard struggles to keep that belonging to non-Muslim foundations.

Today this extortion/spoliation culture has spread to everywhere. The property of anyone declared or assumed to be treacherous can be confiscated. In cities where the HDP won the local elections, the outgoing centrally appointed administrators stripped the municipalities of assets, including even town halls, before the new Kurdish mayors could take office. Members of the Gülen movement, accused of mounting a failed coup in 2016, have similarly had their property seized.

The decision first made to seize the property of Armenians now opens the way to seizures of all types of rights, including the right to live, and is recognised as legitimate. Moreover, nobody can be held accountable. Is it not this culture of impunity that is behind the huge institutional and moral wreckage that has been created in Turkey and internalised by society?

The only exceptions are the crimes against state; they are always punished.

The second stage is to forget and make others forget such practices.

Let me give two examples. One of them is the trial of two generals who carried out 1980 military coup that overthrew the civilian government. A lawsuit was launched in 2012 against two of the five generals of the coup – Kenan Evren and Tahsin Şahinkaya – following a 2010 referendum that removed the article of the constitution that protected the putschists. An Ankara court handed them both life sentences in June 2014 and stripped them of their rank.

While the case was with the Court of Appeals, the two generals died and the court discontinued the trial. The court then overturned the previous ruling and the case was returned to the criminal court, which issued a final verdict on April 12.

The case against Evren and Şahinkaya was dismissed on the grounds that they had died. The court decided there was no reason to confiscate their property and no reason to posthumously strip them of their rank. As with the Armenian genocide, the atrocities of the 1980 coup were also whitewashed.

The second example is being taking place before our very eyes.

During the local election campaign, opposition parties, excluding the HDP, said they would not question the legitimacy of the president. They were saying they would not question the legitimacy of the person who is responsible for everything that has been happening in the country, including the forceful change of regime, since November 2015.

Let us start with the issue of municipal debts. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) said at the weekend he had instructed his party’s incoming mayors not to bring up the problem.

“Do they have debts? Yes, they do have debts. But we told our mayors to never use the rhetoric of having taken over a wreckage,” he told reporters.

Huge damage has been made as a result the ruling party pillaging resources through its control of the municipalities. The details of the pillaging are known to everyone, but the leader of the opposition says he will not ask for any accountability.

What lies here is one of the cornerstones of Turkish politics that is recognised by everyone; the principle of not creating criminals. This has been the case since the genocide and what it means is that some people get away with crimes. Turkey is a museum of malicious acts, crimes that have never been questioned, carried out by perpetrators who have always gotten away with it. As the practice repeats itself in time and creates new criminals, society’s capacity to digest more evil acts becomes stronger and evil becomes ordinary.

What is left is an implicit social contract that is built on the premise that evil acts will be forgotten. That is followed by a culture of refusing to question and memorising the official narrative.

Today those analysts who want to believe the totalitarian regime in Turkey can be ended via elections make such predictions on the premise that new criminals will not be created once more. They think the government will politely hand over power to the opposition and the former rulers will return to their corners knowing they will not be held accountable for their crimes. Otherwise, the present regime, which has engaged in incredible acts of evil and left behind unprecedented institutional and societal wreckage, should be subject to legal process akin to the Nuremberg trials.

Nevertheless, the accumulated evil of the forgotten past returns as social decay. Of course, such social decay can only produce Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Ironically, he is the one making others pay the price for the accumulated evil. As the Turkish saying puts, “Allah does not have a stick”.

By Cengiz Aktar

Source: Ahval News