Trump’s decision to abandon Kurdish allies in Syria wasn’t the first time their invisible nation’s dreams of independence have been dashed – and they’re worried it won’t be the last. Mark MacKinnon returns to Kurdish territory with photographer Andrea DiCenzo to see how its recent years of progress have been undone

Sisters Hamdiyah, left, and Fatiyah Salam embrace at the Bardarash refugee camp in Iraq on Oct. 23, six years after they were separated by Islamic State’s mobilization near their hometown in Syria.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ANDREA DICENZO • GRAPHICS BY MURAT YUKSELIR

BARDARASH REFUGEE CAMP, IRAQ

Tears welled in Fatiyah Salam’s eyes as she hugged her sister, Hamdiyah. Their surroundings, in a refugee camp more than 250 kilometres from their homes, didn’t matter, at least for the moment.

Fatiyah and Hamdiyah hadn’t seen each other since 2013, when Fatiyah fled northeastern Syria as Islamic State fighters approached her hometown. Her sister stayed behind. For the past six years, Fatiyah has lived with her daughter-in-law and grandson in the Domiz refugee camp, on the outskirts of the Iraqi city of Dohuk, wondering when it might be safe to return to the Kurdish part of Syria.

Times seemed to get better in Rojava, as the Kurdish enclave in northeastern Syria is known, especially after U.S. soldiers arrived in the area to help crush the self-declared caliphate. Maybe, the family hoped, they’d be able to move home soon.

The Salam sisters – at 56, Fatiyah is the elder by two years – were reunited on Oct. 23, not in Rojava, but in Bardarash, yet another refugee camp in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq, where Hamdiyah arrived after her own flight from northern Syria. She will spend at least the next three weeks in Bardarash while her documents are processed.

Reuniting in Rojava became impossible when U.S. President Donald Trump withdrew troops from the region earlier this month and greenlighted Turkey’s invasion aimed at driving out the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) militia.

The sisters’ meeting in a refugee camp surely signals the death of the dream of a Kurdish state in northeastern Syria – just the latest time that an independent country called Kurdistan has seemed close, only to prove a mirage.

The fact that the Bardarash camp exists speaks to the never-ending crisis that the estimated 28 million Kurds scattered across Iraq, Turkey, Syria and Iran live in. The camp was initially erected in 2014 to receive refugees fleeing the nearby Iraqi city of Mosul, after it fell into the hands of IS.

It was finally dismantled earlier this year after the last of those refugees trickled home, only to be hurriedly reopened in mid-October to receive the Syrian Kurds who began fleeing after Mr. Trump withdrew American protection from Rojava.

Many Kurds believe the real aim of the offensive ordered by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is to drive Kurds out of Rojava and replace them with ethnic Arabs allied to the Turkish military.

Calamity is heaped upon calamity in this part of the world. The refugees who reach northern Iraq are taken by bus from the border to Bardarash via a route that passes between two sprawling camps that together hold almost 200,000 Yazidi refugees (a religious minority that shares ethnic roots with the Kurds), whose community was targeted for genocide by IS. Their shattered home region remains uninhabitable five years later.

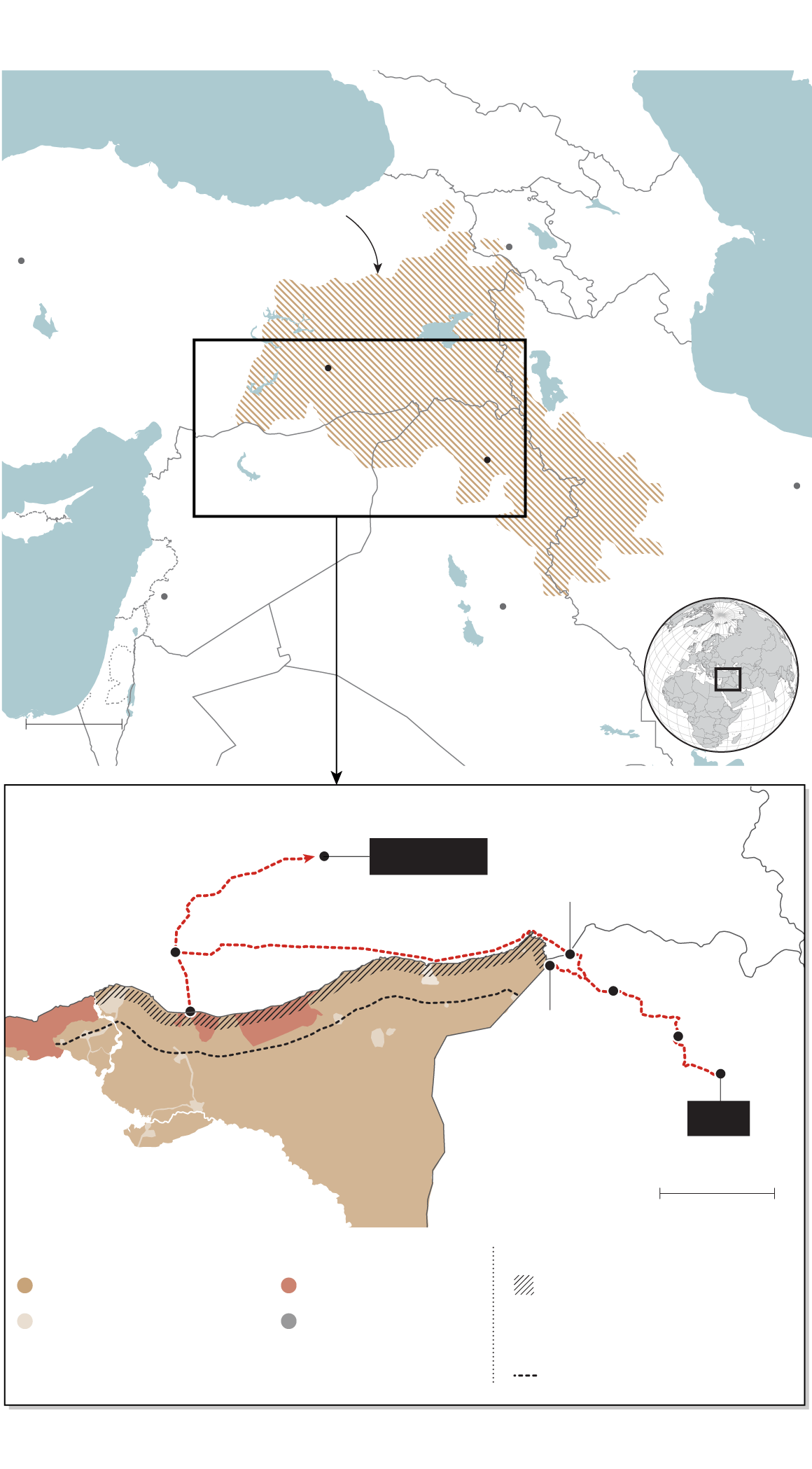

The betrayal of the Kurds didn’t begin with Mr. Trump. Over a 10-day drive across the lands of this invisible country – a journey that took photographer Andrea DiCenzo and I more than 1,000 kilometres through northern Iraq, via refugee camps filling up with Kurds fleeing Syria, and into the repressed southeast of Turkey – many of the Kurds I meet remind me that their tragedy, in its modern form, began a century ago. The great powers who divided up the Ottoman Empire after the First World War decided that the Middle East they were redrawing would be easier to manage without a land-locked Kurdistan in the middle.

Since then, the Kurds have repeatedly risen up in Iraq, Turkey, Syria and Iran, only to be crushed each time – including with the use of chemical weapons by Saddam Hussein’s regime – while the international community looked away. Their language and culture have been systematically repressed by all four states they live under.

“Whatever takes place – chemical bombardments, air strikes, keeping us from having an independent state – the big powers can do it and get away with it,” said Hussein Ali, a family friend who drove Fatiyah from the Domiz camp to Bardarash to meet her sister. “It is not in the interest of the big countries for Kurds to have a country and use our resources to protect ourselves.”

For the past 16 years, ever since Iraq’s Kurds marched south with the U.S. armies that ousted Mr. Hussein, they and their cause had one important ally: the United States of America. That ended on Oct. 6 when Mr. Trump, after a phone call with Mr. Erdogan, abruptly pulled U.S. soldiers out of the part of Kurdistan that lies within modern-day Syria. The Syrian Kurds, who had lost 11,000 fighters while spearheading the defeat of IS, were left to their own devices while their future is being decided between Mr. Erdogan, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Mr. Putin’s client, Syrian strongman Bashar al-Assad.

Suddenly, Iraq’s Kurds, clinging to the autonomous region they’ve carved out in the mountains east of Mosul, worry that they’re a Trump tweet away from a similar fate.

I’d travelled through Kurdistan before, in 2008. Then, I found a people optimistic about the future, fond of the U.S. and all things Western. Retracing part of that journey in 2019, I encountered growing anger at the U.S. and the West, blended with a sense of defeat – as if decades of progress toward the Kurds’ long-held dream of independence had been undone by one poorly considered presidential decree.

Traditional Kurdish rugs are for sale at the Erbil citadel. Much of the KRG’s trade depends on Turkey, putting those who oppose Turkish intervention in Syria in a difficult position.

The capital of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) – the mini-state in northern Iraq that is the closest the Kurds have ever come to a country of their own – was surprisingly quiet when we arrived in late October. A five-day pause in Turkey’s offensive against Rojava was about to expire, and the trickle of refugees crossing into the KRG was threatening to become a flood. But Erbil remained deceptively calm.

The nearest thing to a popular protest came Oct. 21, when a group of young men pelted a U.S. military convoy – which was arriving in Erbil after withdrawing from Rojava – with stones as it travelled to the American military base outside the city. Fearful that such scenes might annoy Mr. Trump into ending U.S. support for Iraqi Kurdistan, too, the KRG ordered the men arrested the same night.

The KRG is caught between a population that instinctively wants to stand with its Kurdish brethren in Syria, and a government that knows that three-quarters of the region’s trade comes via Turkey. Many Erbil residents say they’re boycotting Turkish-made products, but every day, trucks carrying crude oil – the region’s main export – travel down the highway to Turkey, passing trucks heading the opposite direction laden with Turkish-refined fuel and other goods. “In the KRG, our hearts are in Rojava, but our hands are in the pockets of Erdogan. If he closes the border tomorrow, people will starve here,” said Hiwa Osman, a prominent local journalist.

The KRG is afraid to lose what it has. This mini-state stands both as proof that Kurds can govern themselves and a reminder of all the barriers standing between them and genuine independence.

Iraq’s Kurds have their own border regime – this is the only part of the country where Westerners can arrive without first securing a visa – and social policies that are far more liberal than in the areas governed by Baghdad. Women play visible roles in politics and the economy. The Christian and Yazidi minorities say they feel safe here.

The model of a moderate Muslim democracy that Iraqi Kurds have built is a dangerous one in the eyes of its neighbours. Even more threatening was the autonomous region’s status as a proud ally of both the U.S. and Israel, a position that put it at odds with Iran, as well as its proxies in Baghdad and Damascus.

When I made another trip to Erbil in 2014, two of the most optimistic people I met were Tanya Gilly Khailany, a Canadian-educated politician who had served as an MP at the Iraqi parliament in Baghdad, and her husband, Dara Khailany, an adviser to the KRG’s then-prime minister (now President), Nechirvan Barzani.

A catastrophe was unfolding that year, just 80 kilometres to the west of Erbil. IS fighters had seized control of Iraq’s second-largest city, Mosul. The battle to defeat IS would subsequently claim thousands of Iraqi Kurdish lives (in addition to the 11,000 Syrian Kurds killed) as they fought alongside a U.S.-led international coalition to slowly liberate the lands that had fallen under IS control.

But to the Khailanys, there was also opportunity in this crisis. Both spoke of their hope that the countries the Kurds had allied themselves with – first and foremost the U.S. – would finally understand why the Kurds needed to be independent. Iraq and Syria were on the verge of ceasing to exist. Who could argue that the Kurds shouldn’t go their own way?

“Right now, all options are on the table,” Ms. Gilly Khailany, a graduate of Carleton University, told me at the time. Three years later, the KRG made its move, holding a referendum on whether to declare an independent state. Unlike the close-fought campaigns in Quebec and Scotland that the KRG pointed to as models, the September, 2017, vote was a romp, with 93 per cent voting Yes.

But none of the Kurds’ allies – not the U.S., not Canada, which had deployed soldiers to advise the Kurdish Peshmerga forces as they battled IS – backed the Kurds’ desire for a country of their own. When the federal Iraqi army, supported by Iranian-backed Shia militiamen, marched a month later on the Kurdish city of Kirkuk – in an oil-rich region economically vital to the idea of an independent Kurdistan – the Peshmerga withdrew. It had been made clear to them that the Western troops supporting their fight against IS would not help the Kurds defend land they considered their own.

“I still remember that day [of the referendum]. I took my daughter and told her ‘maybe you will see this [an independent state] in your lifetime.’ I didn’t expect it would happen overnight, but we were close. We were almost there,” Ms. Gilly Khailany said, fighting back tears at the memory. “But it didn’t happen that way. We’ve been set back two generations.”

Her husband, from his office inside the KRG headquarters in Erbil, is just trying to manage the shifting realities. The government is facing political pressure – including from activists such as Ms. Gilly Khailany – to do more to support the Kurds of Rojava. But Mr. Khailany is well aware that Turkey could quickly crush the economy of northern Iraq if Mr. Erdogan wanted to.

“I think more people will come to the realization that we have to be realistic. We are in a region where we have to go through these people – who some consider to be our enemies – in order to survive. If we had a border with any European country, or even an Asian country, it would have been different,” Mr. Khailany said. “If you can’t rely on the United States of America, who can you rely on?”

Kurdish peshmerga fighters shop for new uniforms at one of the military markets near the Erbil citadel. Peshmerga have had help from the United States and Canada in battling Islamic State, but not in their ambitions for a country of their own.

A vendor pushes a cart outside Machko Chai Khana, a 75-year-old traditional teahouse at the Erbil citadel.

Divisions among the Kurds themselves have long been a weak point. Even in northern Iraq, the eastern third of the mini-state is governed by the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), a long-time rival of Mr. Barzani’s Kurdish Democratic Party. The two factions fought a civil war in the 1990s, and deep animosity lingers today. Drive east from Erbil and road quality deteriorates as soon as you enter PUK-controlled areas. The money and investment apparent in Erbil isn’t shared with Mr. Barzani’s political rivals. There are also geopolitics at play: To the extent that Erbil is under Turkish influence, the PUK is economically and politically reliant on Iran.

Many see a similar dynamic at play in Erbil’s reluctance to fully back the YPG in this moment. While Iraq’s Kurds instinctively sympathize with their Syrian cousins – there were calls in the regional parliament for Iraqi Kurdish forces to be sent to fight the Turkish army alongside the YPG – the ruling Barzani clan see the YPG as a rival and a nuisance.

In fact, Erbil has often been accused of taking Turkey’s side. Three times during Rojava’s brief flirtation with U.S.-protected autonomy, Erbil closed its lone border with Syria in what critics said was an attempt to score political points with Mr. Erdogan.

“We used to think a [united Kurdistan] was possible. In 2014, 2015, 2016, we heard it was a political project of the U.S. to unite these two [Iraqi and Syrian] parts,” said Abdulselam Mohammed, a 42-year-old Syrian Kurd and YPG supporter I met in a teahouse beneath Erbil’s historic citadel. “Now, I am not optimistic about this, because [Iraqi] Kurdistan is under the occupation of Turkey – economically and sometimes politically.”

Mr. Mohammed was an English teacher before the outbreak of Syria’s civil war, then helped translate documents for the local administration after Rojava gained de facto autonomy. He was forced to move to Erbil in January because his 17-year-old daughter developed leukemia and needed medical treatment she couldn’t receive in Syria.

He said that if he had a choice, he would have remained in Rojava to face the Turkish invasion. Instead, he’s watching from afar, fuming at how quiet the Kurds of Iraq and Turkey remain while their Syrian cousins are driven from their homes.

“Maybe this is our fate, to always be divided, not to be like other nations, who have a home,” Mr. Mohammed said, staring into an almost-empty glass of tea. “It makes us weak and easy to be occupied by our enemies.”

At the Bardarash refugee camp, a convoy arrives carrying new refugees from Syria. The camp, once home to people who fled the Islamic State takeover of Mosul, had been shut down and hastily reopened last month to accommodate people displaced by the Turkish intervention in northern Syria.

On one of the buses of refugees, a woman tries to soothe a child.

The reunions in the refugee camp keep happening. Shortly after we watch the Salam sisters embrace, another convoy of 19 buses arrives, each carrying between 20 and 30 more refugees from Syria. Two women dressed in long, colourful chadors shuffle alongside the convoy as it enters Bardarash, scanning the buses for their own long-lost family members.

A young boy and girl lean out the window of the second-to-last bus, and the two women – aunts the children haven’t seen in six years – reach up and pinch their cheeks in a moment of pure relief.

A few tents away from the one Hamdiyah has been assigned (while she waits for permission to join her relatives in the Domiz camp), 19-year-old Jihan Mahmoud was settling into her third new home in as many months.

Ms. Mahmoud and her family first fled from their Syrian hometown of Kobane in 2013, just ahead of the arrival of the IS. They lived for six years as refugees in Turkey before deciding this summer that it was finally safe to go home. Now they’re on the run again, this time fleeing the country that had until recently given them refuge.

“I don’t really understand why this is happening,” Ms. Mahmoud said, clutching a backpack containing everything she still owns.

Dohuk, a town in Iraqi Kurdistan, was Mr. MacKinnon and photographer Andrea DiCenzo’s next stop en route to the Turkish border.

University students and their families hold a graduation ceremony in Dohuk.

Corruption has done as much to undermine the Iraqi Kurdistan project as any of its neighbours. We drive west from Bardarash to the city of Dohuk, then onward to Iraq’s border with Syria. There, we discover that the YPG – hoping to prevent a mass exodus of Kurds from the region – has sealed its side of the border, forcing refugees to pay smugglers hundreds of dollars a person to escape. When we visit the Faysh Khabur border between Iraq and Syria on Oct. 24, a Peshmerga border guard tells us that not a single refugee has crossed that day, even though 1,700 Syrian Kurds would arrive in Bardarash camp by nightfall after taking a longer and more dangerous journey to cross into Iraq via another route.

Smuggling of a different kind rules the Iraq-Turkey border. When we arrive the next day at the Ibrahim Khalil crossing, Andrea and I are besieged by taxi drivers desperate to be the ones who take us. Driving a Western traveller across the frontier, I’d learned the last time, is excellent cover for a smuggler who doesn’t want the contents of their car to be scrutinized too closely.

Determined not to be part of the racket, Andrea and I found another Peshmerga and told him we didn’t want to cross with bandits. He nodded his head and summoned a minibus forward. “Don’t worry,” he said. “This driver is my friend.”

There were packages of smuggled cigarettes crammed into every conceivable space in the vehicle.

Kurdish regional workers in Turkey, north of the Syrian border. South of that border lies a ‘safe zone’ from which Turkey and Russia want Kurdish forces to withdraw.

A family’s courtyard is shown in Akcakale, home to the Turkish military’s temporary press centre during its crossborder operation in Syria.

AKCAKALE, TURKEY

In Turkey, the chaos of Iraqi Kurdistan disappears, replaced by the grim seriousness of NATO’s second-largest army. The border with Iraq is guarded by green watchtowers. Further in, there are regular military checkpoints where cars are forced to drive through a gauntlet of armoured personnel carriers and soldiers clutching M-16 assault rifles as they stare into passing vehicles.

Rojava is visible out the left window of our car for most of our long drive to the border town of Akcakale, which plays host to the temporary news media centre that the Turkish military has set up for the duration of its cross-border operation.

The frontier with Syria is lined with a three-metre-high concrete wall, topped with razor wire. Pillboxes on dirt mounds allow Turkish soldiers to peer over at what is – when we pass – a Russian-led operation to persuade the YPG to withdraw.

The effort is part of an agreement reached between Mr. Erdogan and Mr. Putin (whose status as the region’s main power broker was confirmed by the precipitous U.S. withdrawal). By Wednesday, the Russian Ministry of Defence had announced that the YPG had withdrawn from the 30-kilometre “safe zone” sought by Mr. Erdogan. Joint Russian-Turkish patrols in the area were due to begin on Friday.

Amid sporadic clashes even during the recent ceasefire, Turkey has vowed to resume its offensive – which it has labelled “Operation Peace Spring” – if the YPG is found anywhere in the border area.

While the Kurds of Syria feel abandoned by their allies, anger at the West is even sharper in Turkey, where the foreign media is seen as having vilified the country by focusing on Kurdish suffering rather than Turkey’s security concerns.

“All the news stories presented by the Western media end up becoming propaganda material that has lost all neutrality,” read one editorial carried last month by Turkey’s state-run Anadolu news agency.

We arrive in Akcakale hoping to collect our media cards – which we’d applied for by e-mail a week earlier – and report the Turkish perspective. Without accreditation, we’re told, we can’t report from the border areas, or even the hospital beside the military media centre, where those wounded in an Oct. 11 YPG mortar attack on Akcakale were being treated.

Each day we’re in Turkey, I message the centre, asking if the media cards are ready. The accreditations never come.

Sanliurfa is home to many refugees from Syria. Turks, Arabs and Kurds have long lived together here, but recent conflicts have inflamed relations between the groups.

Men gather at a bird market in Sanliurfa. Agriculture and animal husbandry are the pillars of the region’s economy.

It’s a 30-kilometre zone on the Syrian side of the border that’s the focus of Mr. Erdogan’s concern – but the tension stretches deep into Turkey, as well.

In Sanliurfa, a historic city where Turks, Arabs and Kurds have long lived cheek by jowl, animosity is rising. Among Turks, there’s near-unanimous support for Mr. Erdogan’s military move against the Kurds of Syria. A long and bloody struggle for Kurdish autonomy inside Turkey waged by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, has eroded any trust that once existed between the two populations. More than 40,000 people have been killed on both sides over four decades of off-and-on fighting between PKK militants and the Turkish state.

Despite the YPG’s participation in the anti-IS coalition, Ankara sees no distinction between the PKK and the YPG, which has former PKK fighters among its top commanders.

While the Kurds, who make up nearly 20 per cent of Turkey’s population, sympathize with their ethnic kin across the border, opinion polls suggest that 75 per cent of the country supports the incursion into Syria. Behind that support are polls showing that almost 80 per cent of Turks think it’s time to start sending back the 3.7 million Syrian refugees who have been living in Turkey since early in Syria’s eight-year-old civil war. The second phase of the agreement between Mr. Erdogan and Mr. Putin provides for exactly that.

As Syria’s Kurds flee their homes, plans are being made to move many of the Syrian refugees currently in Turkey – the large majority of whom are ethnic Arabs – into a “safe zone” the Kurds are leaving. “We think that two million refugees may return to territories liberated from terrorists,” Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said Wednesday.

Amnesty International has accused Turkey of “forcibly deporting refugees.” Turkey says those returning are doing so voluntarily.

The planned resettlement is loathed by many Kurds – who describe it as de facto ethnic cleansing – and baffling even to some of the Syrian Arabs that Turkey wants to move into the border area. “Tel Abyad is not our home, Qamishli is not our home. There’s nothing for us there,” said Fayza Barkat, a 35-year-old war widow and mother of five from Damascus, naming some of the towns the YPG has withdrawn from. “We are from Damascus, Aleppo, Raqqa,” she adds, pointing to neighbours who have gathered to join the conversation.

Mohammed al-Hamed, a 31-year-old refugee from the eastern Syrian city of Raqqa, looks uncomfortable as Ms. Barkat speaks. “We will move there if Erdogan says we should move there,” he quietly replies.

A military-style police vehicle is parked outside the heavily guarded government building in Diyarbakir, a major hub of Kurdish culture.

Men point toward the reconstruction under way in Sur, a Diyarbakir neighbourhood that was mostly levelled by the Turkish military in 2016 after Kurds there declared self-rule.

Before the battle for Rojava, before the battle for Kirkuk, came a 2016 fight for Sur, a neighbourhood of the ancient city of Diyarbakir, one of the world’s biggest centres of Kurdish culture. As with the other fights, the Kurdish side – this time represented by the PKK – tried to establish local self-government. Once again, the Kurds were hopelessly outmatched once the shooting started.

In the summer of 2015, while the eyes of the world were fixated on the rise of IS, Kurdish activists declared self-rule in Sur. Five months later, the Turkish military cracked down, using helicopters and heavy artillery to crush the uprising – levelling 80 per cent of the neighbourhood in the process.

The part of Sur where the PKK made its stand was literally flattened and is only now being rebuilt – although in a concrete-and-glass style that would fit in well in Istanbul, but which clashes with the red-brick architecture around it in Diyarbakir. Many Kurds fear that another historically Kurdish area is about to vanish, and that it will be Turks who move in after the reconstruction is finished.

The siege of Sur marked a sea change in Mr. Erdogan’s relationship with Turkey’s Kurds, many of whom initially supported his Islamist AK Party when he first came to power in the early 2000s. Where once Mr. Erdogan had courted the Kurdish vote – beginning a peace process with the PKK and allowing Kurdish-language classes in schools – in Sur, he switched course.

No longer would Mr. Erdogan try to assuage the Kurds. His new allies would be Turkey’s nationalists and its military. The PKK were again the mortal enemies of the Turkish state.

Three years later, Diyarbakir is still a city on edge. While police cars in Istanbul and Ankara are a mélange of Japanese and European makes, in Diyarbakir, police have for years prowled about in armoured personnel carriers.

The streets have been largely quiet since the beginning of Turkey’s assault on Rojava, but journalists and analysts in Diyarbakir say that shows only the level of repression in the city. Turkey is a NATO ally, and technically still an applicant to join the European Union, but these days, the political atmosphere more closely resembles that of Mr. Putin’s Russia.

Hatice Kamer, a local journalist, said her camera was smashed by police when she tried to cover a small demonstration – she estimates that there were a few dozen people there – on Oct. 9, the first day of the Turkish military operation in Syria. Twenty-four people were arrested.

“It’s simple: If you are a normal citizen and you protest, the police will smash your head. If you are a journalist, the police will smash your camera,” she said when we meet in a dimly lit tea house. “People say there will be a [popular] explosion some day, because we can’t say anything.”

Of all the people we meet on our journey through invisible Kurdistan, Sedat Yurtdas is perhaps the most nervous speaking to a foreign journalist. Mr. Yurtdas was once a prominent politician, a founder of the Democratic Society Party, one of a host of Kurdish political movements that were briefly tolerated before being disbanded by the Turkish courts. He says he’s still facing criminal charges related to his political activities.

Mr. Yurtdas now expresses himself through Turkish-language novels about the conflict. He hopes his fiction communicates that only politics, rather than violence, can resolve the Kurdish issue.

“We are trying to use careful words. Openly, we can’t really share our views,” he said, sitting in a law office across the street from the sprawling Turkish military base in the centre of Diyarbakir. “This can’t go on forever. It has to change.”

By: Mark MAccinon

Source: Globe & Mail

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/VO6UKK2AZNA43MUQSXBK6WTTHA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/N4DISP3IJRFNLJZUQP62VRTHQY.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/44PWGDHC4RELXLN3TX23Q3B7CY.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/LRQDWIMR4ZGLLKXTUXFEN7UJNI.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/DTDXHR6QORFMZH5Q7BJUF2HZUI.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/R5IOSEDF2VH6DBENY7SJLATTYU.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/V75S3XREWVGD5JG4RUHKM2WFJQ.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/ZYATLUGQXJBFNNPEGQIP6WHQYM.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/CYCAXDEFEVCSFBJO4W7MRDYMPM.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/7GZWESRR4RCGZHHDZSIBGKCSSI.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/VDHB5Z5NEZCD5MIFPF2YVQGHSA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/7XHOHUSGO5AX3H3GA6OGIKVOPM.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/QWBOQ3R33ZCXTIOWOZDGRVKFDY.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/EZ3XGGGOSRFSJOQYQCX6FNIJ4Q.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/EHFRRQOOCZAKJDXGHUCCQB57HM.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/KRXTFR53YVCQNNZPFBW3HHZGRE.JPG)