ISTANBUL (Reuters) – A run on the lira proved a pivotal moment for Turkey’s financial markets in 2018, prompting action from Ankara that has tilted the economy inward and frightened off foreign investors.

Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan, his government and his deputies have said the measures taken tmsnrt.rs/378W6fq, which sparked an exodus of foreign money, were needed to stabilize the economy and bolster belief in the lira, which has dropped 36% in two years.

But the impact on investment in what was once a darling of emerging markets has been dramatic. The World Bank estimates that net foreign direct investment, which fell 30% last year, will not regain 2018 levels until after 2021.

For import-dependent Turkey, some analysts say the danger is that this outflow could over time starve the Middle East’s top economy of funds and stall Erdogan’s recovery plans.

Former Turkish Treasury research associate Ugras Ulku, who now heads the Institute of International Finance’s (IIF) regional Emerging Markets research, said that “tighter control on financial markets, risks including U.S. sanctions and Turkish borrowers’ inability to access foreign funding” mean the country may miss out on foreign cash.

Overseas investors have largely steered clear of Turkey’s sovereign bonds, despite a once-in-a-decade rally since May, while some players are reconsidering their strategies.

HSBC is considering selling its Turkish bank, sources familiar with the matter told Reuters last week, while Citigroup (C.N), one of the top foreign banks in Turkey, transferred at least two foreign exchange and rates traders to London from

Citi and HSBC both declined to comment.

The fallout has also led to losses for Goldman Sachs (GS.N) and other foreign firms who were burnt in 2019 when Turkey directed its banks to withhold liquidity from a key London swap market to defend the currency, two bankers familiar with trading activity said.

Goldman Sachs declined to comment.

The swap market move was one of dozens of dictats and regulations to defend the lira, from setting deposit rates at lenders to tapping the central bank’s reserves.

New rules and regulations spiked to 3,800 in 2018 from 551 in 2007, a World Bank analysis here shows.

Interest rate cuts, along with a surge in public spending and a push to get state-owned banks to lend more, have helped Turkey recover from recession. But a rapid uptick in lending in an already indebted economy and a widening budget deficit risk storing up trouble, ratings agencies and economists say.

Turkey’s Treasury and its central bank each declined to comment. Erdogan’s office was not available to comment.

A government effort to boost lending a year ago, by cutting the amount of interest Turkish savers could get from their deposit account, prompted some to keep their spare cash in dollars or euros, according to bankers and central bank data.

State banks have since March tapped up to $32 billion of central bank reserves in buying up lira, a Reuters analysis of the central bank’s balance sheet shows.

The state banks then re-deposit lira at the central bank, officials and bankers with knowledge of this loop told Reuters.

An official at one state lender said Turkey’s banks are now staffed by traders at all hours, part of what some call a “national team” ready to respond to any lira weakness.

Despite this support, the lira skidded 11% last year, with the biggest slide between March and May, as interventions began.

For a timeline of post-crisis interventions, see: here

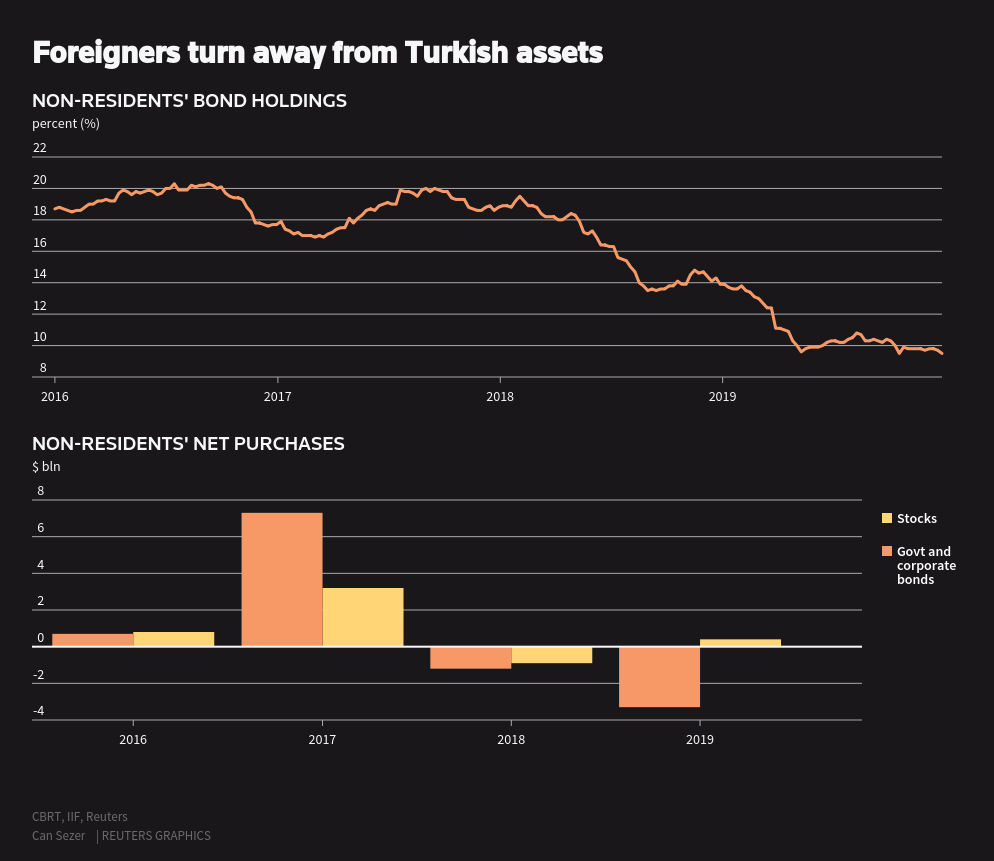

GRAPHIC: Foreigners turn away from Turkish assets – here

Slideshow (5 Images)

SWAP MARKET

Last year non-residents sold a net total of $3.3 billion in Turkish bonds, compared to purchases of $7 billion in 2017, IIF data shows. That means local investors mostly profited as Turkey’s benchmark 10-year yield dropped below 10% from 21% in May, thanks mostly to monetary easing and a drop in inflation.

The foreign flight is partly a response to the government’s approach to markets after a 2017 referendum handed Erdogan wide-ranging authority over the courts, military and economy.

The clearest signal of an intensification of this intervention came days before nationwide local elections in March 2019 that would deal a blow to Erdogan’s party, more than a dozen investors, bankers and Turkish officials told Reuters.

That was when Turkish state lenders suddenly cut short-term lira funding to the London swap market, which was popular for hedging and shorting, traders and bankers said, sending rates rocketing to 1,200%.

The move reversed a volatile drop in the currency, but left big European and U.S. banks scrambling to cover positions and sell Turkish bonds, several sources have told Reuters.

Goldman Sachs was among the hardest hit, two of them said.

A person familiar with Goldman’s operations said that while the Wall Street firm faced the same tough conditions as others, it had not logged “material” losses.

Reuters could not confirm positions in the market, where bilateral trades are made privately.

The lira swap market, a source of funding for Turkish mortgages, has since collapsed, Bank of England data here shows, and several foreign investors say they no longer trust it.

Since the March episode, foreigners have dumped Turkish debt even while most other emerging markets benefited from a global hunt for yield. Data from Turkey’s bank regulator shows they owned only 8.3% of the debt in mid-January, down from nearly 17% in early 2018.

“Subliminally they know that after all they have done they have beaten their guests and those guests will never come back,” a Turkish investment adviser, speaking on condition of anonymity, said.