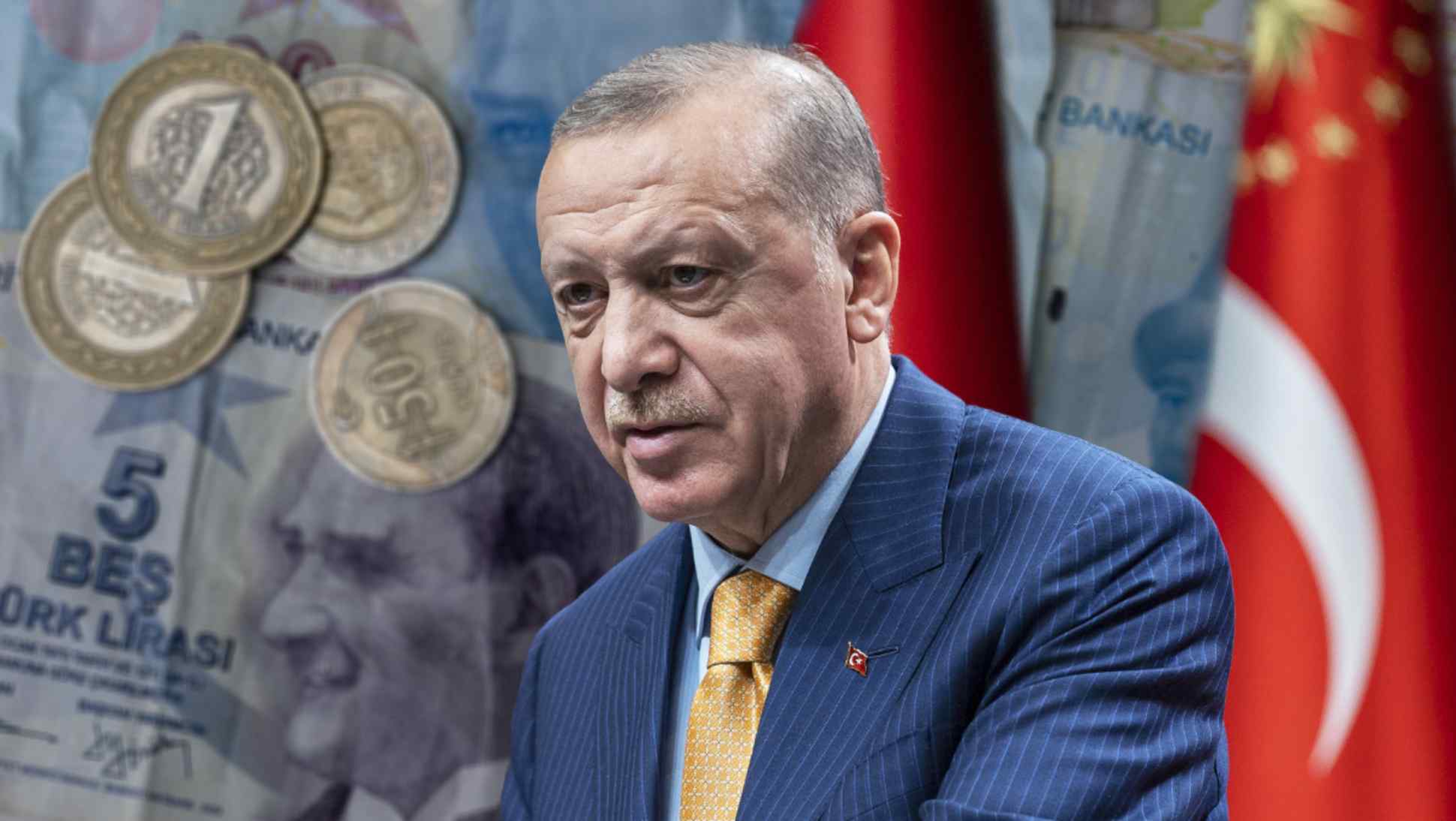

Architect of past growth blasts president for letting currency slide and cash flee

ANKARA — After going on at length about Turkey’s breakneck growth from 2003 to 2013, a period during which the country became an emerging market darling to international investors, the once and long-served economy czar took a deep breath and sighed. The subject had just turned. “What, when and how did it all go wrong?”

“I think there are series of episodes, like a Netflix drama,” Ali Babacan told Nikkei Asia at the modest Ankara headquarters of the centrist Democracy and Progress Party. Babacan founded the party a year ago, after resigning from the ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, run by Turkey’s omnipotent Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who before becoming the country’s president in 2014 spent 11 years as prime minister.

Babacan in 2001 was a founding member of the AKP. Over the 13 years to 2015, when he left government, he became the AKP administration’s longest-serving cabinet member. He served as the foreign minister, state minister and deputy prime minister. After serving as a lawmaker for three more years, he ultimately left the AKP in 2019 before founding the centrist Democracy and Progress Party, whose Turkish acronym, DEVA, means “remedy.”

DEVA’s formation last March represented a challenge to Erdogan.

“During the first years of his rule, if two or three ministers objected on a matter, [Erdogan] could not proceed,” Babacan told Nikkei. Those turned out to be the AKP’s golden years. The party took power in 2002 and delivered democratic reforms, kicked off European Union accession negotiations and embraced prudent macroeconomic policies that brought high economic growth and delivered welfare and public services to citizens. Ali Babacan says that after three electoral victories — in 2002, 2007 and 2011 — and nine years in power, Erdogan began disregarding those he once confided in. (Photo by Momoko Kidera)

Ali Babacan says that after three electoral victories — in 2002, 2007 and 2011 — and nine years in power, Erdogan began disregarding those he once confided in. (Photo by Momoko Kidera)

By 2013, per capita gross domestic product had more than tripled in nominal terms, to $12,600. Before the AKP came to power, the country experienced decades of hyperinflation, with the year-on-year rate soaring higher than 100% in some months.

During those lean decades, Turkey had sought help from the International Monetary Fund close to 20 times. But in 2008 it graduated from its final bailout program, fully repaying loans to the fund in 2013.

Throughout the ride, Babacan was in the driver’s seat, picking up throngs of foreign investors, from Tokyo to Silicon Valley. Many of these financiers, he said, still regularly meet with him, seeking his insights.

“However, after three electoral wins [in 2002, 2007 and 2011] and nine years in power, starting from 2011, [Erdogan] grew too self-confident and started not to consult anyone. … Institutions [were] being downgraded, and he started to attack the central bank.” Then Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in Istanbul, in 2015. The two men are now political rivals. © Reuters

Then Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in Istanbul, in 2015. The two men are now political rivals. © Reuters

A series of events in early November tell how centralized Turkish politics has become.

Around 2 a.m. on Nov. 7, a Saturday, news broke that the official gazette had published a presidential decree signed by Erdogan, sacking central bank Gov. Murat Uysal and replacing him with Naci Agbal, an experienced bureaucrat and former finance minister. It was the second time in 16 months that Erdogan had sacked a central bank governor.

The second shock came on Sunday evening — via an Instagram post in which then Finance Minister Berat Albayrak, Erdogan’s son-in-law, posted his resignation. Albayrak has not been seen since.

The president on Monday night officially announced that the resignation had been accepted. On Tuesday, Lutfi Elvan, another veteran bureaucrat and ex-minister, was appointed to replace Albayrak.

Now that political revolving door has some foreign investors looking at the country with skepticism.

Erdogan is notorious for abhorring high interest rates; the economic model he had been pursuing uses an expansion in bank lending to ignite domestic demand. He calls high interest rates the “mother of all evil” and occasionally blames shadowy foreign “interest rate lobbies” when bond yields increase. Similar to how Donald Trump treated the U.S. Federal Reserve, Erdogan constantly pressures the central bank to lower interest rates.

When he was in government, Babacan, a staunch defender of the central bank, tried to temper Erdogan’s impulses. But after Babacan left the government in 2015 — and following a bloody coup attempt in 2016 — the emerging market darling began to lose its charm.

Without its defender, the central bank became increasingly pressured by Erdogan and his entourage to lower interest rates; as a result, more and more foreign investors pulled out their money, leading to a depreciation of the lira.

The trend was especially pronounced for the two years up to Albayrak’s departure. While Erdogan’s son-in-law was steering the economy, the lira lost half its value against the dollar.

Albayrak was pursuing an unorthodox policy mix, pushing for aggressively cutting interest rates, pressuring bank regulators and forcing commercial banks to lend at real negative interest rates. With borrowers thus being paid to take money, a massive credit boom resulted, igniting the economy.

The downside was a ballooning current-account deficit, a currency plunge and close to 15% inflation in 2020.

In 2018, Turkey also began paying the price for the arrest of an American pastor, a rare and audacious move against a fellow NATO member. The U.S. retaliated with sanctions that spooked foreign investors and locals alike. As investors fled, Turks rushed to buy hard currencies and gold to protect their savings.

But thanks to the unorthodox policy mix — and despite the pandemic and inflation — Turkey’s GDP in 2020 grew 1.8%.

The spurt came at a high cost to the central bank, which in a two-year span burned through $130 billion in foreign currency reserves to defend the lira.

This “was a terrible strategy,” professor Hakan Kara of Bilkent University, once the central bank’s chief economist, told Nikkei Asia. It “will appear in international macroeconomy textbooks on what not to do.”

Kara was removed from the post in 2019. He said his sacking was due to political pressure. “They were trying to adopt an unsustainable framework,” he said. “Technical expertise of people like me was no longer needed under such a nonscientific approach.

“Once the central bank started to sell reserves, all international institutions and foreign investors started to calculate [how much was left] every day.”

The central bank’s gross reserves currently stand at $92 billion, but Kara calculates that when currency swaps with foreign central banks and local banks are excluded, net foreign reserves are at minus $46 billion, leaving Turkey vulnerable to financial turmoil.

When they came aboard in early November, new central bank chief Agbal and Finance Minister Elvan quickly started to unwind Albayrak’s legacy with a series of moves. For his part, Agbal halted the selling of foreign reserves. He also raised the policy rate by a total of 675 basis points, taking the rate to 17% in December.

Agbal has also been talking up the importance of price stability, reiterating his intention to “maintain the tight monetary policy stance until we bring inflation down to 5% at the end of 2023.”

And on Thursday, when the central bank starts its next monetary policy meeting, financial market players expect him to raise the policy rate by another 100 basis points.

His actions and comments have lured back some foreign investors. Erdogan seems to be on board for now. Such “bitter pills,” he said, are necessary.

On Friday, Erdogan rolled out an economic rejuvenation program and vowed to bring the inflation rate below 10%. The headquarters of Turkey’s central bank, in Ankara. By one observer’s calculation, the bank has net foreign reserves of minus $46 billion, when currency swaps with foreign central banks and local banks are excluded. © Reuters

The headquarters of Turkey’s central bank, in Ankara. By one observer’s calculation, the bank has net foreign reserves of minus $46 billion, when currency swaps with foreign central banks and local banks are excluded. © Reuters

Turkey, however, is “not completely out of the woods,” Kara said. The new economic policy officials “have still not attempted to solve long-term structural issues, but just picked the low hanging fruit. … Success will depend on … structural reforms such as improving democratic institutions, rule of law, fundamental rights and freedoms, normalizing foreign relations with traditional allies.”

Babacan agrees. He said Agbal and Elvan “are good tacticians” but wonders about their bureaucratic upbringings. “My reason for highlighting that they have a bureaucracy background,” he said, “is they tell what is necessary but when they are instructed, they obey the instruction.

“Will President Erdogan be patient enough for rate hikes to produce results in taming inflation? It is a big open question.” While the central bank targets inflation at 5% by the end of 2023, financial market surveys forecast 7% for the next 10 years.

Agbal’s job has become more difficult in recent weeks. A four-month lira rally stalled around the end of February and the currency erased all of its 2021 gains.

The reversal coincided with a change in rhetoric from Erdogan, his chief economic adviser Yigit Bulut — who once claimed foreign powers were trying to kill Erdogan through telekinesis — and new Finance Minister Elvan. In breaking a four-month silence, the three began to defend former Finance Minister Albayrak and his free-money track record.

Turkey is suffering from a concurrent exodus: Talent is also escaping.

Erdogan has “pushed out talented human resources,” Babacan said, “or good people left themselves.” As a result, governmental institutions and the AKP have less capacity to get things done. “The governing mentality must change,” Babacan went on, “and mentality will only change with the change of the president and the small group around him.”

The eventual fate of Albayrak is gaining attention. Rumors are floating around that he will be reappointed as vice president or cabinet minister, or be given a senior role within the party. The rumors are heaping more pressure on the lira, market traders say. Rumors are flying that Berat Albayrak will be rehabilitated and make his way back into Erdogan’s cabinet, or be given a senior party post. © Turkish Ministry of Finance and Treasury/Getty Images

Rumors are flying that Berat Albayrak will be rehabilitated and make his way back into Erdogan’s cabinet, or be given a senior party post. © Turkish Ministry of Finance and Treasury/Getty Images

Emre Peker, Europe director for the Eurasia group, said, “It is more likely that Albayrak’s political rehabilitation will not materialize this year but regardless of whether or not he returns to politics in an official capacity, he will likely exert influence behind the scenes.”

Economic policy is also likely to be influenced by the political calendar: A presidential and general elections are set for 2023, when the republic also celebrates its centennial. The Erdogan administration once set ambitious economic targets, such as becoming a top 10 economic power and reaching $25,000 per capita GDP by 2023. But the nation has been shedding per capita GDP for seven years now, with the measure falling to $8,600 in 2020, a 14-year low.

Babacan and Kara predict Erdogan’s patience for high interest rates might last a year while his policy team fights to control inflation and stabilize the lira. Both predict that in 2022 Erdogan could call for snap elections, presidential and parliamentary, if the economy recovers.

But Erdogan’s showing in the 2018 presidential election, which he won with 52% of the vote, demonstrates that he would have a difficult go in another electoral race.

On the other hand, the opposition is weak, fragmented and has to find a way to appeal to the religiously conservative majority of voters who pull the lever for AKP politicians.

As for the splintered opposition, ex-Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, another former Erdogan ally, has also formed a party. Along with DEVA, this and other newly born conservative parties have the potential to strip votes from the AKP.

In opinion polls, however, Babacan’s and Davutoglu’s parties score in the low single digits. In Babacan’s view, Erdogan’s economic missteps will end up costing the AKP some of its support. The new parties could potentially tilt the balance of power and become kingmakers in the process.

Babacan, no longer sighing, insists DEVA’s existence is giving Erdogan “sleepless nights.”

By: SINAN TAVSAN and MOMOKO KIDERA

Source: Nikkei Asia