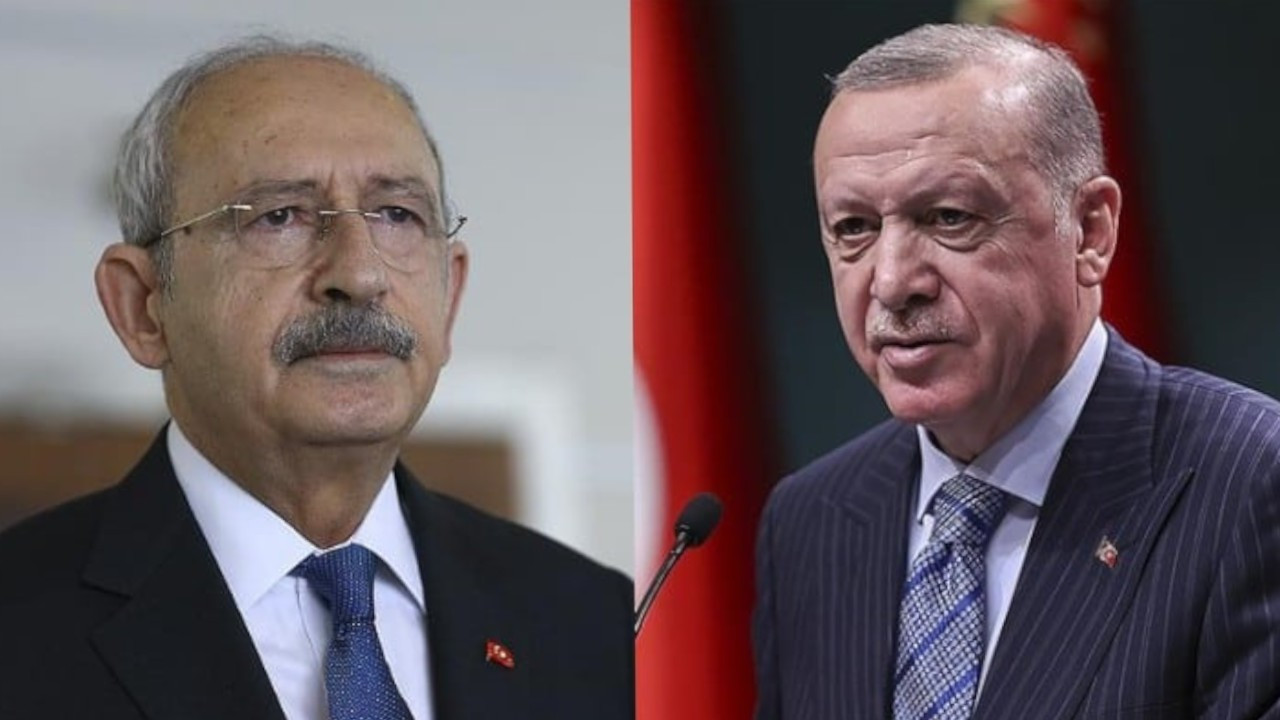

As there are only days to Turkey’s general elections, the opposition candidate, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, is closer to a victory more than ever. Most polls show Kilicdaroglu ahead of Erdogan for months. Polls can always be misleading, but in Kilicdaroglu’s case, his nationwide popularity supports the numbers. Even in Van, an Eastern Anatolian city where the Republican Party has been historically weaker, an unprecedented crowd welcomed Kilicdaroglu. This is certainly good news for the opposition. But the question of election security still waits for an answer. Rather than expecting Erdogan to concede defeat, the opposition would be well advised to formulate a strategy for addressing the potential scenario in which Erdogan declines to do so.

Making a dictator concede defeat is not an easy task. According to a study based on The Rulers, Elections, and Irregular Governance (REIGN) dataset, only 12 percent of dictators who suffered an election loss left their offices. One important parameter is the regularity of elections. The dictators who held regular elections have shorter tenures than the dictators who held irregular elections. But more importantly, the existence of an escape route or a ‘feasible alternative’ is a stronger determinant. Indeed, military dictators, who have a chance to return to barracks, have a higher rate of accepting election defeats. The article reminds us how Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet maintained his control over the armed forces even after abdicating power. Pinochet designated himself as a senator-for-life and granted his fellow military officers immunity.

In the Turkish case, Erdogan does not seem to have much alternative other than clinging to power. In the case of a Kilicdaroglu government, Erdogan might stand trial for corruption, human rights violations, ties with radical groups, and others. Thus, he is more likely to follow the path of Belarusian President Lukashenko, who won a landslide victory at overtly rigged elections, or Donald Trump, who refused to admit defeat. After all, Erdogan showed his likely course of action in previous instances. In June 2015 general elections and the 2019 local elections in Istanbul, Erdogan did his best to override results.

In this respect, Kilicdaroglu should reveal at least the outlines of his strategy in case of election fraud or denial. First, the opposition, as a united front, should declare that they will not be part of the Parliament and not recognize the legitimacy of rigged election results. Thus, Erdogan will not enjoy the façade of democracy and legitimacy that the somewhat diverse structure of Turkish politics provides.

Another step that Kilicdaroglu can take is civil disobedience or peaceful demonstrations, which can mobilize millions of his supporters. Although its success rate has been decreasing in recent years (thanks to improving surveillance capacity of the states), it has been successful in many previous cases, like in colored revolutions.

For sure, even if the opposition leaders stay silent, rigging elections or rejecting its results may trigger widespread demonstrations all over the country, like what happened in Belarus, recently in Iran, or the Gezi protests in Turkey. Yet, Kilicdaroglu’s precommitment to a strategy is important for three reasons. First, it can discourage state institutions from eliminating the last instance of democracy. The tendency towards political inertia, or a belief in the status quo, may lead state bureaucrats to serve Erdogan’s efforts to negate the election results obediently. However, if these bureaucrats perceive that Erdogan’s authoritarian rule will lead to irreversible one-party dictatorship, they are less likely to pursue his agenda recklessly.

Second, increasing the opposition’s determination to save democracy might cause fissures within the governing coalition, particularly among the bureaucrats. Erdogan’s regime is not a single united front but a coalition that includes actors even with ultra-secular or Kemalist agenda. As the chances of opposition victory increase, more actors will consider jumping from Erdogan’s sinking ship or, at least, they will be less likely to commit to Erdogan.

Kilicdaroglu’s resistance will also shape the international community’s attitude. Erdogan’s victory is not the worst thing for Turkey’s relations with the EU or the US. Turkish-American relations, especially from the perspective of Washington, have already been in a precarious state. Furthermore, Washington does not appear to have any hope of improvement in the near future. Thus, Erdogan’s election victory is not the worst-case scenario for the West. But, the idea of democracy’s official ending in a NATO country will certainly complicate the situation for the Western countries. If Kilicdaroglu shows his resoluteness to defend election results, this might increase the chance of international diplomatic and economic pressures on Erdogan.

Kilicdaroglu’s willpower can encourage desperate voters and bureaucrats too. The role of despair cannot be underestimated in Turkish politics. Most people believe that Erdogan will win some way or another even if he loses – the idea which demoralizes the opposition. Those people or groups are less likely to struggle for democracy. Nevertheless, Kilicdaroglu’s leadership can unite undecided or hopeless voters.

Kilicdaroglu’s performance so far should not be belittled. Yet, securing and executing elections are as important as winning them. Kilicdaroglu’s rival is a Machiavellian strongman who believes that the ends justify the means. Hence, Kilicdaroglu must convince people that he will not concede to Erdogan’s abolition of democracy’s last remaining institution in Turkey.

By: Haşim Tekineş

Source: Institute for Diplomacy and Economy (instituDE)