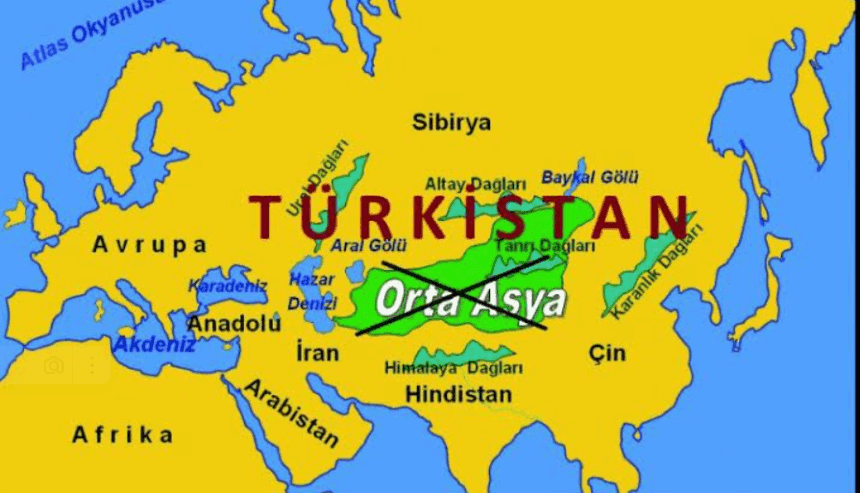

Turkey’s education ministry has formally decided to replace the term “Central Asia” with “Turkistan” in the national school curriculum, in a move Ankara says is meant to reinforce unity across the “Turkic world.”

Education Minister Yusuf Tekin announced in Ankara that from now on, the region long taught to Turkish pupils as Orta Asya will appear in textbooks as Türkistan. He framed the change as part of the new “Türkiye Yüzyılı Maarif Modeli” (Century of Türkiye Education Model), saying that the word “Central Asia” was consciously introduced into the literature to fragment the Turkic world and that Turkey is now pushing back against such “imperial” concepts.

Tekin argued that previous governments allowed foreign categories to shape how Turkish students imagined the region. According to him, aligning the curriculum with “the Turkish state tradition” means reviving historical terminology and emphasizing values like human rights and the rule of law as understood through that tradition.

Renaming a region in the classroom

In international usage, Central Asia refers to the five post-Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, and in some scholarly works also includes China’s Xinjiang region. The term itself is relatively modern, popularized by European and Russian geographers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

“Turkistan” or “Turkestan,” by contrast, is an older, civilizational term. For centuries it denoted a broad belt of territory inhabited largely by Turkic-speaking peoples and Islamized under Arab and later Turkic rule, long before the borders of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China carved the region into separate states and provinces. Under tsarist and early Soviet rule, a Turkestan Governorate/ASSR existed as a large administrative unit before being dissolved and subdivided into republics like the Kazakh and Uzbek SSRs—precisely to dilute any pan-Turkic political imagination.

By reintroducing “Turkistan” into schoolbooks, Ankara is deliberately privileging this older civilizational vocabulary over the more neutral, geographic one. News outlets across Central Asia and the Turkic world reported the change as a conscious attempt to “strengthen national identity and patriotism” and to underline the cultural and historical bonds among Turkic-speaking states.

The power of names

Names are never just labels; they encode entire narratives. The word “Central Asia” suggests a region defined by its position on the map: a landlocked zone between Russia, China, South Asia and the Middle East. “Turkistan” instead suggests a historic homeland of Turkic peoples stretching across today’s Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and parts of western China—and, in some nationalist imaginations, even beyond.

The term also carries contemporary political weight. Uyghur groups use the name “East Turkestan” for the region the Chinese state calls Xinjiang, framing their cause as one of national self-determination for the Turkic and mostly Muslim inhabitants. Turkey has long been a sympathetic but cautious observer of the Uyghur question; embedding “Turkistan” into the curriculum inevitably echoes the Uyghur vocabulary, even if Ankara avoids making explicit connections to Xinjiang policy.

At the same time, the standard Central Asian definition includes Tajikistan, a predominantly Persian-speaking country whose identity is tied more to Persianate than Turkic heritage. Treating the whole region as “Turkistan” risks flattening this diversity and foregrounding Turkic identity over others, a point that some regional analysts have already raised.

Education as pan-Turkic soft power

The curricular change dovetails with Turkey’s broader effort to build a Turkic sphere of influence through the Organization of Turkic States (OTS). The OTS, founded in 2009 and headquartered in Istanbul, brings together Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan as full members, with several others as observers. In recent years, it has adopted the flagship document “Turkic World Vision – 2040”, which imagines deeper political, economic and socio-cultural integration, including explicit cooperation in education and youth policy.

Within this framework, schooling becomes a tool of education diplomacy. Studies of the OTS agenda note that education is framed as a key channel for building a shared Turkic consciousness across borders, from student exchanges to curriculum coordination and common history projects. Replacing “Central Asia” with “Turkistan” inside Turkish classrooms fits neatly into that strategy: it habituates Turkish students to see the region not just as a distant ex-Soviet periphery, but as part of an extended Turkic home in which Turkey is the most populous, militarily strongest and institutionally most established state.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has personally underlined this narrative, presenting the coming decades as an “era of the Turks” and explicitly linking his “Century of Türkiye” vision to closer alignment with Central Asian partners through the OTS. When the head of state is talking about a Turkic century and the education minister is renaming Central Asia as Turkistan, the symbolic and geopolitical layers are hard to miss.

A domestic battle over the curriculum

Inside Turkey, the renaming lands in the middle of a long-running struggle over how history and geography should be taught. Tekin situated the decision in the work of a curriculum committee evocatively titled “Gönül Coğrafyamız”—literally “Our Geography of the Heart”—tasked with rethinking how Turkey’s neighbourhood is represented in textbooks.

The same package of reforms also touches other highly sensitive topics, including Ottoman policies toward Armenians, where terminology changes are widely seen by critics as attempts to soften or sidestep the concept of genocide. Supporters of the reform argue that the entire curriculum needs “decolonization” from Western or Soviet-era narratives and should be rebuilt around an authentic Turkish and Islamic worldview. Opponents see ideological engineering aimed at cultivating a more nationalist-conservative generation and closing the space for pluralist or critical readings of history.

Tekin himself is a polarizing figure. He played a central role in the post-2016 purge of the education sector, which saw tens of thousands of teachers and academics dismissed over alleged links to the Gülen movement after the failed coup attempt. For his critics, this background reinforces the idea that curriculum debates in his hands are less about neutral pedagogy and more about loyalty, identity and regime stability.

Regional sensitivities: Moscow, Beijing and beyond

Outside Turkey, reactions are likely to be cautious but attentive. In Russia, analysts have long watched pan-Turkic currents with suspicion, especially in relation to Turkic minorities within the Russian Federation and Moscow’s own influence in Central Asia. The symbolic return of “Turkistan” in Turkish textbooks cuts against the Soviet cartographic legacy that broke the region into separate national republics; in Russian commentary it is already being interpreted as another step in Ankara’s campaign to enhance its footprint in what Moscow still considers its traditional sphere of influence.

In China, the term inevitably intersects with the Uyghur question. While Beijing and Ankara officially emphasize strategic partnership and economic cooperation—including through Belt and Road corridors that pass through Central Asia—Chinese officials are acutely sensitive to any mainstreaming of “Turkistan” or “East Turkestan” language in foreign public discourse, particularly in countries such as Turkey with strong cultural ties to Turkic peoples.

For the Central Asian states themselves, the reaction is likely to be more nuanced. Governments in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan already participate enthusiastically in OTS activities and welcome Turkish investment, cultural exchanges and security cooperation. At the same time, they have carefully cultivated multi-vector foreign policies that balance Russia, China, the West and regional players. They may appreciate Turkistan-centred language as affirming shared heritage, while quietly resisting any implication that they are junior members of a Turkey-led bloc.

For Tajikistan, the picture is more sensitive. Being non-Turkic yet geographically embedded in the same region, Dushanbe has historically been wary of discourses that package the entire area as a Turkic homeland, fearing cultural marginalization and potential cross-border identity politics.

Redrawing the map in young minds

In the end, the renaming of “Central Asia” to “Turkistan” is not just a semantic tweak buried in history textbooks. It signals a larger ambition: to align Turkey’s school curriculum with a geopolitical project in which Ankara sees itself as the cultural and political centre of a wider Turkic world.

For Turkish students, future classroom maps will no longer show a neutral Central Asia bounded by five independent republics. Instead, they will see Turkistan, a term that implicitly links them to a larger, historic community stretching from the shores of the Caspian to the fringes of China. Whether that mental map will remain primarily a cultural bond or evolve into a more assertive political agenda will depend on how Ankara, its Turkic partners and neighbouring powers choose to navigate the symbolic weight of this single, carefully chosen word.