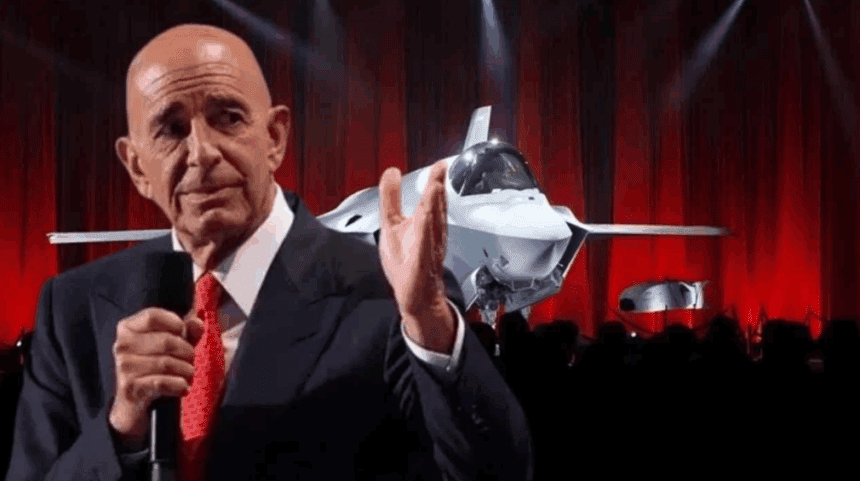

The United States has signaled fresh momentum in negotiations over Turkey’s possible return to the F-35 stealth fighter program, but Washington is standing firm on its demand that Ankara fully divest from the Russian-made S-400 air defense system, according to US Ambassador to Turkey Tom Barrack.

In a statement posted on X on Tuesday, Barrack said talks between Ankara and Washington had become “more constructive” in recent months, crediting what he called an improved personal rapport between US President Donald Trump and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Barrack underlined, however, that the legal and political condition at the heart of the dispute remains unchanged.

As spelled out in US law, he said, Turkey “must no longer operate nor possess the S-400 system” if it wants to rejoin the F-35 program, stressing that this requirement continues to apply despite the new diplomatic opening after nearly a decade of deadlock.

A Dispute Rooted in the S-400 Purchase

The rift dates back to Trump’s first term, when Washington removed Turkey from the multinational F-35 consortium in 2019 after Ankara took delivery of the Russian S-400 system despite repeated warnings from the US and other NATO allies.

US officials argue that deploying the S-400 alongside NATO air assets poses an unacceptable security risk, potentially allowing Russia to gather sensitive data on F-35 radar signatures and other stealth characteristics. The acquisition triggered sanctions under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), which still apply to Turkey.

Barrack said the latest dialogue marks “the most fruitful conversations we have had on this topic in nearly a decade,” adding that both sides are now exploring “a realistic path” that would meet US security requirements while addressing Ankara’s longstanding demand to return to the F-35 program.

“Our hope is that these talks will yield a breakthrough in the coming months that meets both the security requirements of the United States and Türkiye,” he said.

‘Four to Six Months’ Timeline

This is the second time in a week that Barrack has publicly raised the prospect of Turkey rejoining the F-35 consortium.

Speaking at a conference in Abu Dhabi last Friday, he said Ankara had already addressed part of Washington’s concerns regarding the operability of the S-400 system, noting that the batteries are currently not in active use. However, he emphasized that Turkey’s continued possession of the hardware remains a central point of friction.

Asked whether Turkey was moving closer to disposing of the S-400s, Barrack replied, “Yes,” and predicted that the remaining issues could be resolved within “four to six months” if the current trajectory in talks continues.

Complex Choices Over the S-400

Turkey’s 2017 deal with Russia for the S-400 was valued at around $2.5 billion and included two complete batteries and more than 120 long-range 48N6 missiles. The question now is whether Ankara is prepared to relinquish the systems entirely, and under what terms.

It is unclear whether Moscow would agree to buy back the S-400s at anything close to the original price, or whether Turkey would instead try to transfer them to a third country or dismantle them under an arrangement acceptable to both Washington and NATO.

A complete removal of the S-400 infrastructure from Turkish territory—potentially via resale to Russia—would remove one of the main legal and political obstacles to Ankara’s return to the F-35 program and reopen the possibility of acquiring fifth-generation US jets.

From 100 F-35s to a Mixed Fleet

Before its expulsion in 2019, Turkey had planned to purchase 100 F-35A aircraft and was a key industrial partner in the project, producing several components for the jet.

Officials now say Ankara’s current request is for 40 F-35s, reflecting the fact that Turkey has diversified its airpower plans in the intervening years. The country has invested heavily in its indigenous fifth-generation fighter, the KAAN, which Turkish officials say is expected to enter service in 2028.

At the same time, Ankara is seeking to modernize its existing fleet through the acquisition of Eurofighter Typhoons and new-build US-made F-16s, as well as upgrade kits for its older F-16s, to avoid a capability gap until KAAN and any future F-35 deliveries materialize.

Congress and Regional Skepticism

Even if the executive branches in Washington and Ankara reach a technical and political understanding, any sale of advanced US defense systems to Turkey will still require approval from the US Congress. Lawmakers have repeatedly used this leverage in recent years to pressure Ankara on issues ranging from Syria policy and Eastern Mediterranean tensions to human rights.

Greek and Israeli officials have privately and publicly raised concerns about Turkey’s potential return to the F-35 fold, arguing that it could alter regional airpower balances and complicate their own security planning. Such objections could feed into congressional debates, further complicating the approval process.

Personal Diplomacy at the Center

The renewed push comes against the backdrop of intensified personal diplomacy between Trump and Erdoğan. The two leaders discussed the S-400 issue during their meeting at the White House in September, where Trump hinted that he might be open to a compromise that would bring Turkey back into the F-35 program.

At the time, Trump said Erdoğan was “going to do something for us,” without specifying what concessions he expected from Ankara. For US officials and lawmakers, “something” has long been understood to mean a verifiable and irreversible solution to the S-400 problem.

Two Key NATO Militaries

Despite the dispute, Washington and Ankara remain central pillars of NATO. The United States and Turkey field the alliance’s two largest armies and provide critical capabilities on NATO’s eastern and southern flanks.

For now, the path back to the F-35 for Turkey runs through a single, non-negotiable condition laid out in US law: Ankara must not only refrain from operating the S-400, but must no longer possess it. Whether Turkey is willing—and able—to make that leap will determine if the current “new momentum” ends in a genuine breakthrough or yet another missed opportunity.