- Kerem Mamut was held for three months in Turkey deportation centres

- He was suspected of communicating with two people who had links to a terrorist organisation

- He believes Turkey may have been cooperating with Chinese authorities

Late at night on October 31 last year, Wang Yi and her husband Kerem Mamut had just returned to their home in Basaksehir, a middle-class Istanbul neighbourhood, after a visit to the doctor to treat one of their children who had a fever.

The couple who are from China’s Xinjiang province, but have lived in Turkey for a decade, then heard loud bangs at the door.

“The neighbours,” they said to themselves, until one of their daughters ran upstairs. It was the police.

Twenty members of a Turkish special police unit detained Mamut and took him to a nearby police station to question him.

Mamut, a Chinese Uygur who held a Turkey residence permit, was suspected of communicating by phone with two people who had links to a terrorist organisation.

For three months, he was held at two deportation centres in Turkey without charge. His family and lawyer speculate he might have been targeted as part of China’s efforts to pressure Turkey to repatriate some ethnic Uygur Muslims living abroad.

The 53-year-old Chinese passport holder, who owns restaurants in Turkey and China, was held for two months at the first deportation centre.

There he said, his interrogators regularly asked if he wanted to be sent back to China.

Late December, Mamut was transferred to another deportation centre in Izmir, a city on Turkey’s Aegean coast.

Then on January 25, Mamut was unexpectedly granted conditional release.

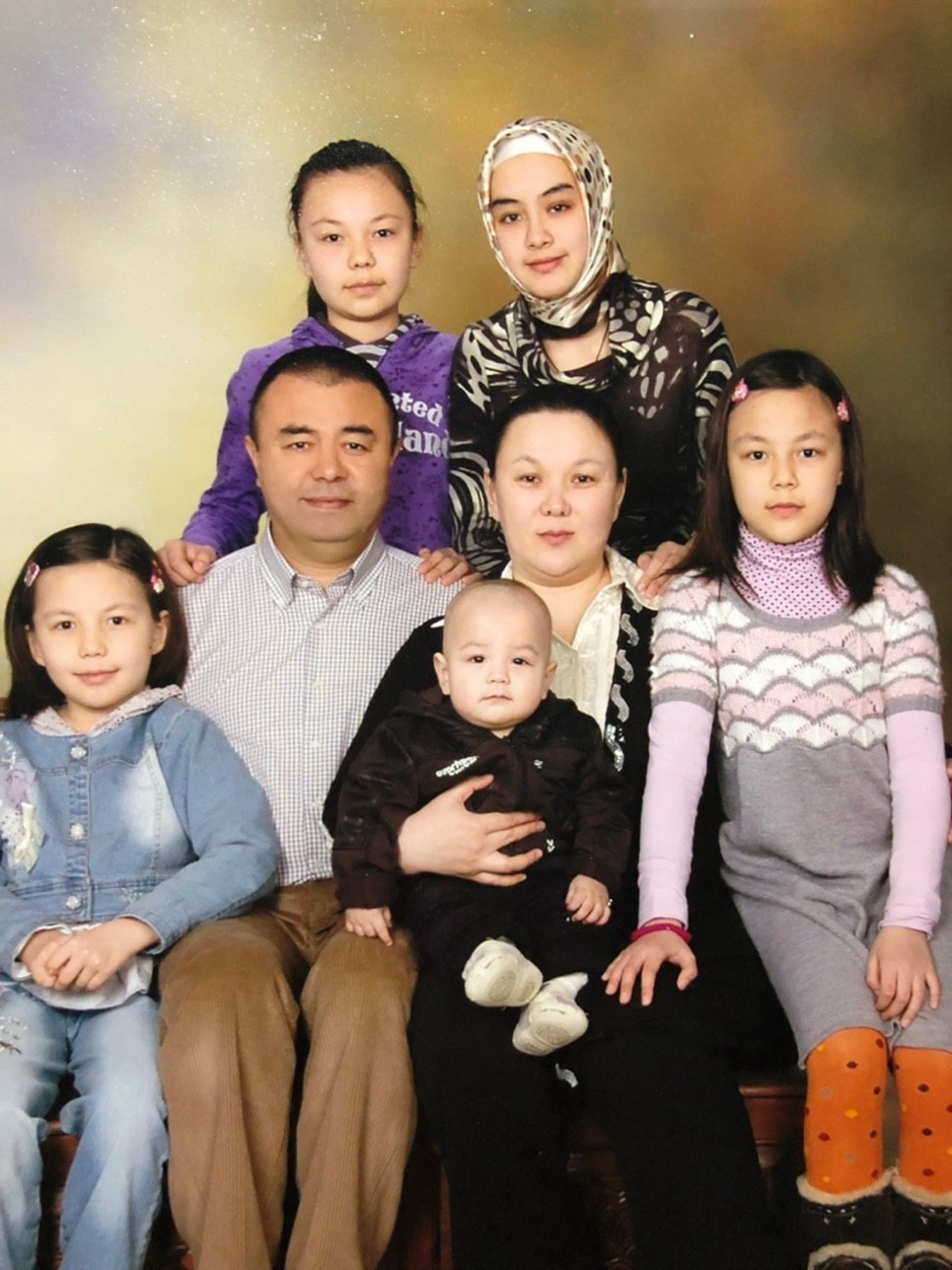

“These accusations of terrorism are so remote from who I am,” Mamut told South China Morning Post in Istanbul last week during an emotional gathering with his family.

That evening, Mamut hugged his 10-year-old son Babur, whom he did not see during his three-month detention.

“We initially thought it might be a misunderstanding and that they would investigate quickly,” said Mamut’s wife Wang about her husband’s detention.

“But as time went on, we started to think that things were not that simple.”

Wang, a Han Chinese mother of four who holds Turkish citizenship, took over running the couple’s Chinese-Uygur restaurant while Mamut was being held.

The restaurant called Kroren, in Istanbul’s conservative Fatih district, is well-known to both Uygur and Chinese people, including employees of China’s consulate in the city.

Mamut’s lawyer, Lokman Akcay, called the case a “massive mystery” and has yet to be shown concrete evidence that proves his client’s alleged links to a terrorist organisation.

China’s crackdown on its Uygur Muslim minority in Xinjiang province has forced many to flee to countries such as Afghanistan, Kazakhstan and Turkey.

Muslim Uygur children taught the ‘forbidden language’, far from their restive homeland in China’s Xinjiang

Some have established organisations that protest China’s presence in what some still call “East Turkestan”, where they say Uygurs face cultural and religious repression.

After 2010, when a series of terrorist attacks both in Xinjiang and in the rest of China involving Uygurs, and the onset of the Syria civil war, Beijing’s relationship with the Uygurs worsened.

According to some estimates, up to 5,000 Uygurs went to fight with militant groups in Syria, and Beijing feared some could return to carry out attacks in China.

In 2014, China launched its “Strike Hard” campaign against violent extremism and tightened restrictions on Uygurs, including the practice of Islam and the teaching of Uygur language.

A UN human rights panel in August last year estimated that a million ethnic Uygurs and other Muslims in China were being held re-education camps.

Beijing calls the camps “vocational training centres”, designed to help people drawn to extremism be reintegrated into society.

China has used economic pressure to persuade several countries, including Turkey, a close economic and political ally, to support its position on the Uygur issue and its fight against extremism.

Turkey, whose currency lost 30 per cent of its value in 2018, seems to be receptive.

Its energy and transport sector secured a US$3.6 billion loan from Industrial and Commercial Bank of China last summer, while the number of Chinese tourists jumped by 80 per cent in 2018, according to Turkey’s Culture and Tourism Ministry.

After the riots in Xinjiang’s capital Urumqi in 2009 which claimed at least 200 lives, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, then prime minister, compared the events to a “genocide”.

He has yet to publicly comment on China’s crackdown on Uygurs and the camps.

Turkish media have also refrained from hard-hitting reporting on the country’s sizeable Uygur community, especially after a 2017 trip to China by the Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu, during which he vowed to prohibit anti-China media reports.

Mehmet Ogutcu, a former Turkish diplomat in Beijing, calls the relationship a “delicate balance” especially for Turkey.

In the past Turkey welcomed thousands of Uygurs that left China. Some were extremists who transited through Turkey to fight for Islamic State in Syria.

“Over the past few decades the Chinese have insisted all along on signing security and counter-intelligence agreements with Turkey in order to deal with extremist Uygur militants,” Ogutcu said.

Similar arrangements were made with countries such as Pakistan and Egypt, he added.

In 2017, Malaysia deported 29 Uygurs suspected to be involved with Islamic militants. Two years earlier Thailand deported more than 100 Uygurs back to China sparking an outcry.

“However, Turkey could not comply with such requests, making it clear that Turkey is a democratic country and cannot act upon one-sided intelligence,” Ogutcu said.

Turkey still discreetly welcomes some Uygur refugees – the latest case last October, after it allowed in 11 men who were released from detention in Malaysia.

How China is trying to impose Islam with Chinese characteristics in the Hui Muslim heartland

That may come as some comfort to Mamut, despite Turkish authorities cancelling his residence permit after his arrest.

In the autumn on 2018, the Chinese authorities in Urumqi raided and closed down two branches of Miraj, one of the restaurants that Mamut helped establish.

Radio Free Asia reported that it was because the establishments, which served Uygur food in traditional settings, “promoted Uygur cultural identity”. Two hundred staff were reportedly arrested.

Because Mamut and his family had not had contact with their friends and family in Xinjiang, Wang said they only learned of the raids in December.

In January, a friend in Xinjiang managed to call to tell her that all properties in Mamut’s name had been seized.

“I am sure there is seriousness on the Turkish side to make sure that any extremist Uygur element posing a credible threat to China’s security should not be tolerated and be allowed to be a sore point in the strategically crucial relationship,” Ogutcu said.

“Yet, there may be cases where the intelligence requests from China might point to peaceful law abiding Uygurs living in Turkey as well.”

US lawmakers nominate jailed Uygur Ilham Tohti for Nobel Peace Prize, seeking global pressure on China

A decision on Mamut’s case will be made in a few months, according to his lawyer Akcay, who was confident his client would not be deported to China.

Turkey is bound by both domestic law and international agreements such as the European Convention on Human Rights, which prevents it from deporting a person if they could be subjected to the death penalty, torture, and cruel or degrading treatment or punishment.

Turkey signed an extradition agreement with China in 2017 but has yet to ratified it. In November 2018, the two countries signed several deals enhancing judicial cooperation.

A spokesperson for Turkey’s Ministry of Justice, when asked about Mamut, said it did not comment on specific cases.

When asked about law enforcement cooperation between Turkey and China, the spokesperson said that Turkey received communications from China about Chinese citizens, including Uygurs.

During her husband’s absence, Wang doubled her efforts to keep the family united. She would drive several times to the capital, Ankara, to see their daughter Arzu, a teenage ice hockey prodigy who plays for Turkey’s national team.

After Mamut returned to Istanbul after his release from detention last month, he slept for two days. The first night he reappeared at his restaurant, regular customers stood up to greet him.

With businesses in both Turkey and in China, he said he did not try to get Turkish citizenship like his wife and children did after they arrived in Turkey in 2009.

He had returned Xinjiang for personal visits, but things did not go well, he said.

“The police would call me repeatedly, I would be taken in for questioning. But I am used to it. It has been like this in Xinjiang for 20 years now,” Mamut said.

However, he hoped for a better future for all people in Xinjiang.

“I believe there is a misunderstanding between the Han and the Uygurs,” he said.

“They see us as dirty thieves. I want to promote a dialogue between our two cultures. There is no other way, we have to understand each other.”

Wang recalled her last trip to Urumqi, her hometown in Xinjiang in the summer of 2017.

The local authorities came to her home, took her mobile phones, credit cards and confiscated her Turkish passport for three months.

Finally in October the police let her leave. They escorted her to the airport and her multi-entry visa to China was cancelled.

She was told she was being treated this way because of her husband, she said.

Around the same time, she said her husband’s son from a previous marriage, Sami Kelimu, was taken into custody and was probably being held in a camp.

“Turkey would have to look very hard on the evidence that China provides,” said Ogutcu, the former diplomat referring to Mamut’s case.

“Because if the benchmark is that they are engaged in illegal activities against China’s security (and this is covered by security cooperation and counterterrorism intelligence sharing), they have to work together on that.”

Akcay, Mamut’s lawyer, speculated that China provided Turkish authorities with intelligence on his client.

The Chinese embassy in Ankara did not answer the Post’s emailed questions about Mamut’s case.

Sophie Richardson, China Director at Human Rights Watch, said that any government that yields to pressure from China to forcibly return Uygurs would be “violating a fundamental human rights obligation not to send anyone back to a situation in which that person faces a well-founded fear of persecution”.

What happens to Mamut in the next few months will be closely watched by the Uygur community in Turkey.

He has been ordered to report to an immigration office every week until a decision on his case is made.

Surrounded by his wife and children in his restaurant, Mamut said he was tired of trying to stay out of China’s reach.

“In China, and now in Turkey too, if they don’t like you, they can do these things to you,” he said.

Source: South China Morning Post