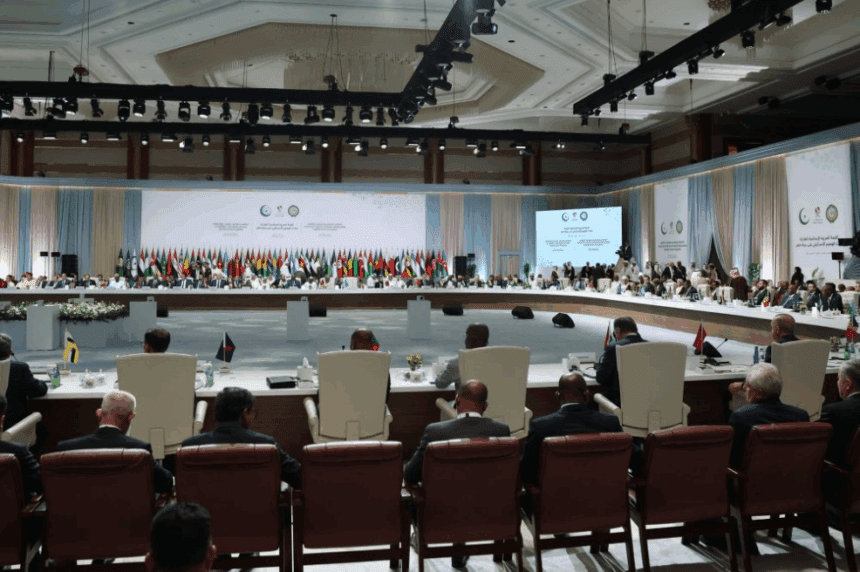

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan told an emergency Arab–Islamic summit in Qatar that Israel’s leaders should be brought before international justice mechanisms and urged Muslim and Arab states to tighten economic pressure on Israel. He framed the gathering as a show of “unconditional support” for Qatar after last week’s Israeli strike in Doha, and described Israel as a “terror mentality” that “feeds on chaos and blood.”

He also called for written decisions from the meeting, closer cooperation to achieve self-sufficiency in key sectors over “the next 10 years,” and reiterated Ankara’s political backing for a Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital. He also said Turkey has ‘halted’ all trade with Israel “for 1.5 years,” a claim that follows Ankara’s ‘full trade freeze‘ announcement on May 2, 2024 and subsequent ‘steps‘ reported this summer

Erdoğan’s speech in Doha—urging Muslim and Arab states to “squeeze Israel economically” and to mobilize international law—lands on a long paper trail. For at least two decades of Erdoğan-era governance, Turkey–Israel commerce expanded from the margins of the ledger into a durable, near-structural relationship. According to Turkish Statistical Institute data, bilateral trade was $1.41 billion in 2002; by 2022 it had climbed to $8.91 billion, a six-fold jump that set repeated records. Even when politics froze (recall 2010), the trucks, ships and ledgers kept moving, and by 2016 trade still totaled $3.86 billion, with Turkish exports up 6% that year. By late 2022, Turkish sources again flagged a “new record,” with $8.6 billion in the first ten months alone. The granular year-to-year line wiggles in places—but the broader Erdoğan-era picture is unmistakable: a mostly rising curve across twenty years.

That historical arc explains why Ankara’s recent sanctions rhetoric has struggled to convince markets that the corridor is truly shut. On May 2, 2024, Turkey declared a halt to all bilateral trade “until” a permanent ceasefire and unhindered aid to Gaza, building on an April restriction list that targeted 54 export categories. Yet UN Comtrade still records $2.87 billion in Israeli imports from Turkey in 2024, leaving Turkey as Israel’s 5th-largest supplier; the Bank of Israel later concluded that the embargo’s macro impact was limited because importers found substitutes without sustained price spikes. The headline sounded maximalist; the data read minimalist.

The latest turn—Aug. 29, 2025—tightened things further: Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan told parliament that Turkish ports were closed to Israeli ships, Turkish-flag vessels were barred from Israeli ports, and parts of airspace were newly restricted. But the policy architecture stopped short of a universal embargo on all Turkey↔Israel cargo. Turkish port agents have been informally required to present letters stating that a calling vessel has no Israeli links and carries no military or hazardous cargo destined for Israel—a compliance framework, not a blanket prohibition. In practice, that framework leaves space for third-country carriers to keep shuttling.

Sure enough, the tape keeps catching what podium language denies. AIS schedules this month show the Liberian-flag ro-ro Trans Carrier running İskenderun→Haifa on Sept. 7–8, while the Hong Kong-flag Nysted Maersk sailed Mersin→Haifa on its published rotation—plain, direct Turkey→Israel legs by foreign-flag tonnage. We have previously catalogued this pattern as a “ban that bends,” with Israeli-linked and Turkish-flag traffic curbed, but third-country hulls still able to move Turkey–Israel cargo.

Energy flows make the contradiction even harder to square with today’s moral tenor. During 2014–2015, Israeli refineries repeatedly received crude lifted at Ceyhan from Iraq’s Kurdistan Region; the Financial Times reported that Israel took as much as three-quarters of its oil from those Kurdish shipments over several months—barrels that moved through Turkey’s pipeline and export posture. Meanwhile, Israel has long sourced a large share of its crude from Azerbaijan, loaded at Ceyhan after traveling the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline across Turkey; multiple industry snapshots have put that share around ~40% in recent years. Even this summer’s organic-chloride contamination scare at Ceyhan did not durably interrupt BTC loadings; BP said cargoes resumed after additional testing, with on-spec oil reaching the tanks again by July 31. The geography that empowered Turkey to be an energy crossroads also bound it into Israel’s refinery diet—whether Ankara liked the optics or not.

The sectoral ledgers tell the same story in miniature. In 2024, Israel’s iron & steel imports totaled roughly $1.95 billion, with $210.8 million supplied by Turkey—about 11%. When a June 2025 social-media storm alleged a ship named VELA had loaded “tons of steel” in Mersin bound for Israel’s arms manufacturers, Turkey’s official Disinformation Center publicly checked manifests and denied the claim. Activists still traced the hull toward Ashdod; the government still insisted the scandal was a mirage. The episode captured the fog that has surrounded enforcement since 2024: legalistic rules and political thunder on one side, contested logistics on the other.

It is tempting, in the wake of Doha’s rhetoric, to say that history no longer matters. But two decades of trade integration—mostly rising, record-setting, year after year across the Erdoğan era—do not unwind by declaration. If Ankara truly intends the “economic squeeze” it extols, it has two honest paths: either codify a universal prohibition on all Turkey→Israel loadings and Israel-bound cargoes touching Turkish territory (regardless of flag, owner, or consignee), or admit that Turkey will target Israeli-affiliated and Turkish-flag movements while leaving a corridor for foreign-flag carriers and transit energy flows that underpin Turkish leverage. Either path is defensible; pretending there is no choice is not.

For now, the map is winning. Ships still clear Mersin and İskenderun for Haifa under non-Turkish, non-Israeli flags; BTC/Ceyhan still feeds tankers that can reach Ashkelon; and UN Comtrade still registers a Turkey→Israel channel resilient enough to blunt embargo headlines. Erdoğan’s words in Doha search for moral clarity. Two decades of trade—and the infrastructure that made it possible—keep restoring ambiguity.

By: News About Turkey (NAT)