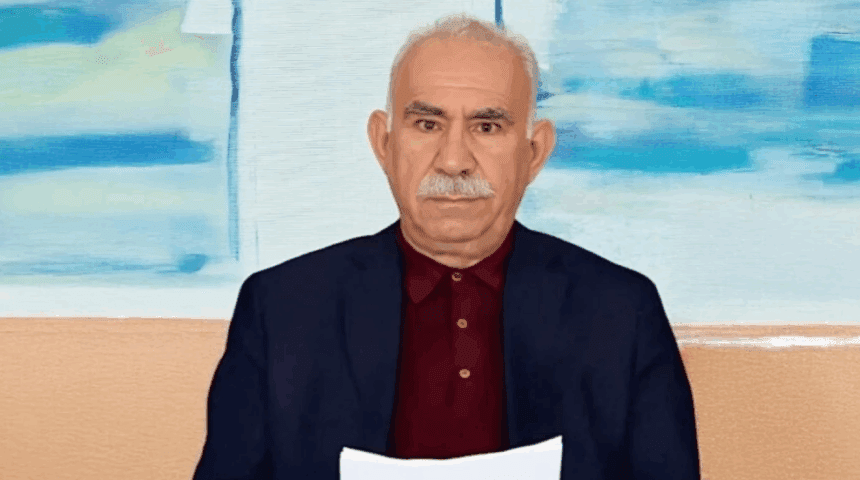

Jailed PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan has accused Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) of trying to manufacture a sense that it has already defeated the PKK, warning that Kurds “have alternatives” if Ankara does not move beyond rhetoric to binding guarantees. His remarks were relayed by the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party) at a news conference in Diyarbakır attended by DEM Deputy Co-chair Tayip Temel, HDK Co-Spokesperson Meral Danış Beştaş and Diyarbakır lawmaker Cengiz Çandar.

According to the party officials, Öcalan condemned what he described as a manipulative, “deceitful” approach by the government and insisted that Kurds would not remain “without status” in the new century. The emphasis, they said, is on concrete legal architecture—guarantees that would lock in any settlement rather than leave it to political goodwill. DEM figures characterized this as Öcalan’s toughest message since the current round of talks picked up momentum.

The present track traces back to October 2024, when Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) leader Devlet Bahçeli—normally a hard-line ally of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan—publicly called on Öcalan to urge the PKK to end its armed campaign. In late February 2025, Öcalan answered by calling on the organization to disarm and disband. The PKK followed in the spring by declaring that it had “completed its historic mission,” and in July staged a symbolic weapons-burning ceremony near Dukan in northern Iraq. These gestures created expectations that Ankara would reciprocate with a legal framework for demobilization and reintegration.

At Tuesday’s briefing, the DEM Party outlined what it views as essential steps for a durable settlement. It wants formal recognition of Kurdish language rights, stronger local governance and a halt to the practice of appointing government trustees in place of elected mayors. It is pressing for revisions to Turkey’s expansive counterterrorism laws, which have long been used to prosecute Kurdish politicians, and for activation of a “right to hope” for Öcalan—a pathway that could, based on behavior and time served, allow a prospect of conditional release under law. DEM also urged that Öcalan be heard by the parliamentary commission established in August to shepherd the process.

The “right to hope” debate has become a focal point. In essence, it concerns whether life sentences—especially aggravated life terms—are genuinely reducible in practice, giving prisoners a realistic prospect of eventual release if they meet strict legal criteria. Kurdish groups and rights advocates argue that without such a mechanism, any peace architecture lacks credibility for the movement’s base, while Ankara has so far avoided committing to a reform that would include Öcalan.

Government statements in recent weeks have stressed vigilance against spoilers and emphasized monitoring the PKK’s dismantling. Yet Kurdish representatives say the state has not tabled the “bold steps” they seek: legal guarantees for disarming militants, codified protections against politically driven dismissals of elected officials, narrower definitions in security legislation and a clear reintegration path that moves rank-and-file out of legal limbo. Continued detentions of Kurdish politicians and the replacement of mayors by trustees have further eroded trust, even as the ceasefire environment largely holds.

All this is playing out against a long and brutal history. Designated a terrorist group by Turkey and its Western allies, the PKK launched its insurgency in 1984, and the conflict has claimed around 40,000 lives. Today, with gestures already taken on the insurgent side, the trajectory depends on whether Ankara anchors the process in enforceable law and institutional reform. Supporters of the talks argue that a parliamentary timetable that includes hearing from Öcalan or his legal team, revisiting sentencing and municipal governance rules, and clarifying protections for those who disarm would signal that the state intends a peace that outlives the political moment.

For now, Öcalan’s warning—that projecting a “false victory” without structural change risks squandering another opening—captures the fragility of the moment. The coming weeks will reveal whether the parliamentary commission moves beyond procedural meetings to substantive proposals and whether the government is prepared to convert a season of gestures into a legally durable settlement to the Kurdish question.