US Ambassador to Turkey Tom Barrack and Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan have both moved in recent days to place Ankara at the heart of any post-war settlement in Gaza, underscoring how Washington and Turkey envision a shared – if still contested – role in shaping the territory’s future.

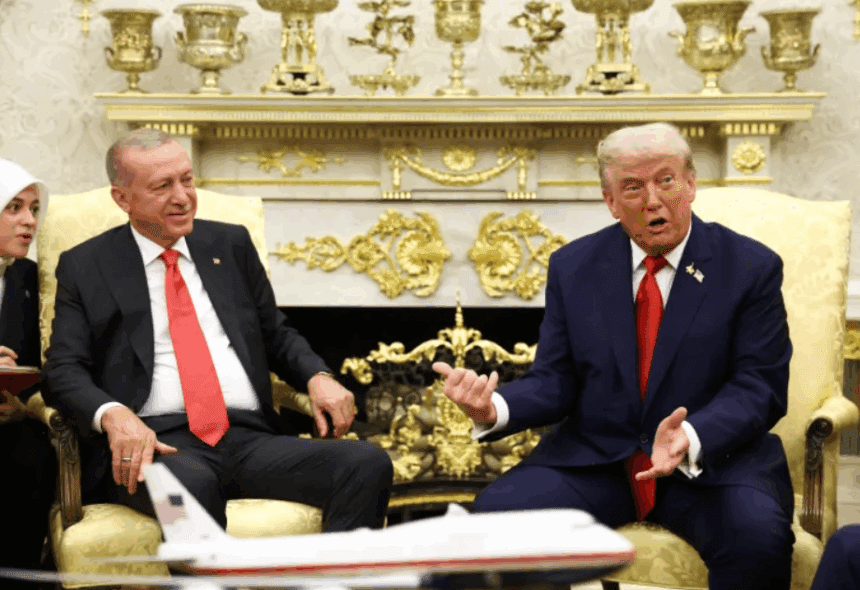

Speaking at the Milken Institute Middle East and Africa Summit in Abu Dhabi, Barrack described the personal relationship between US President Donald Trump and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as a “bromance” and “a great thing,” arguing that this unusual closeness is now a key pillar of US policy toward Ankara.

“Look, the great thing is we have a bromance between our two presidents,” Barrack said in a public conversation with Bloomberg editor Paul Wallace, contrasting the current dynamic with past periods of sharp tension between the NATO allies.

He rejected the familiar Western accusation that Erdoğan is seeking to resurrect an Ottoman-style empire. “Our belief, the U.S. belief, is he’s not interested in extending the Ottoman Empire,” Barrack said, adding that for Erdoğan “taking care of Istanbul and Ankara is enough.”

At the same time, Barrack delivered a sweeping indictment of Western policy in the region. “Since the fall of the Ottoman Empire, everything the West has done has been a mistake,” he argued, saying that from Versailles to Oslo, efforts to impose “tribes and flags” through colonial mandates have consistently failed. In his view, what does work are “benevolent monarchies” that align religious and political authority while managing the distribution of wealth and resources. “The Middle East has $9 trillion in investable capital, 20 million barrels of oil a day, 30% of global resources, and 20% of global capital,” he said. “And we’re still fighting tribes and flags. It’s ridiculous.”

Barrack portrayed Turkey as a core security partner for Washington – “our largest NATO ally besides America,” as he put it – and stressed its pivotal geography between Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia, with the Bosporus Strait a vital artery for trade and energy. At the same time, he noted that Turkey still feels locked out of Western political “clubs,” pointing to the European Union’s continued reluctance to admit Ankara despite what he called a hardworking population and an economy in crisis.

He acknowledged that under Erdoğan – in power for more than two decades as prime minister and then president – Turkey has pursued an assertive, often controversial foreign policy: buying Russian air-defence systems, launching cross-border operations in Syria and Iraq, and clashing with EU states, even as it remains a NATO member hosting key US military facilities and acting as a hub for refugees, gas and trade.

Barrack said Washington still sees Turkey as indispensable within what he called a regional “tapestry” that stretches from Azerbaijan to Armenia and includes new transport and energy corridors running from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean.

Turning to Turkey’s relations with Israel, Barrack was blunt about the damage done by Israel’s Gaza campaign and Ankara’s harsh criticism of it. “So the simple answer, it’s bad,” he said when asked to assess the relationship. He noted that, like other governments in the region, Turkey has reacted strongly to the death and destruction in Gaza and now foregrounds calls for a two-state solution or similar political framework.

Barrack also said that remarks by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu are “just rhetoric,” expressing confidence that “Turkey and Israel will find their relationship at some point.”

He underlined how quickly the economic relationship has deteriorated. “Go back to October 5th,” he said. “On October 5th, the [Turks and] Israelis had a trading relationship and a foreign trade agreement with a surplus of about $7 billion. It vanishes in an afternoon.” Inside Turkey, he added, many now view Israel as “Greater Israel,” seeing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s strategy not as defence but territorial expansion, citing repeated Israeli strikes in Syria and Lebanon.

Yet Barrack predicted that, once the current phase in Gaza ends and a broader regional architecture emerges, Ankara and Tel Aviv will be pushed back toward cooperation. “At the end of Gaza, which is a dramatic step forward, I think that you will see at some point in time Turkey and Israel finding a relationship,” he said. “Whether it’s the Abraham Accords or the Solomon Accords or a hybrid, it makes sense.”

He also highlighted Turkey’s channels to Hamas and its role in hostage negotiations. “Quite honestly, Turkey, at the end of these discussions, stepped in to have the final discussion with Hamas side by side with Qatar, which saved us,” Barrack said. “It really got the US to a decision point.”

Against that backdrop, Barrack voiced strong personal support for Turkey joining an international stabilization force that Trump wants to see deployed in Gaza in stages after an Israeli withdrawal. “My personal opinion, which is beyond my job description, is absolutely,” he said when asked if Turkey should take part. If he were advising Netanyahu, he added, he would urge him to accept Turkish participation, arguing that Turkey’s controversial relationship with Hamas could be turned into an asset – though he admitted he does not expect Israel to agree.

Fidan: Hamas to Step Back, New Palestinian Authority and ISF in Gaza

While Barrack was making the case for Turkey in Abu Dhabi, Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan used the Doha Forum in Qatar to sketch out what Ankara’s concrete role in Gaza might look like.

In an interview with Reuters on the sidelines of the conference, and in a public session at the forum, Fidan outlined a plan under which Hamas would step back from governing Gaza in favour of a new Palestinian civil administration, backed by a vetted local police force and an international peace mission that Turkey wants to join.

Fidan said Hamas is ready to relinquish day-to-day control of the territory, but only after a “credible” Palestinian administration and a functioning, professional police force are in place. It is, he argued, “neither realistic nor doable” to demand that Hamas give up its weapons as a first step in the current ceasefire roadmap without those institutions on the ground.

Under the proposal he described, the new Gaza police force would not include Hamas members and would operate under the protection of an International Stabilization Force (ISF) deployed inside the Strip. Fidan said the United States is pressing Israel to accept Turkey as a contributor to that force, echoing Barrack’s own enthusiasm for Turkish participation.

The Doha Forum, an annual gathering of political leaders and experts, is this year heavily focused on the US-brokered ceasefire efforts in Gaza and on how to move from a fragile pause in fighting to a permanent halt to Israel’s offensive and the reconstruction of the devastated territory. Qatar’s prime minister has called the moment “critical,” emphasizing that the current arrangement is still only a partial truce: Israeli forces remain inside Gaza, and violence has not fully stopped.

More than 70,000 Palestinians have been killed and well over 150,000 wounded since Israel began its campaign in 2023, according to Gaza’s health ministry, with most of the enclave’s 2.1 million residents displaced and basic infrastructure in ruins. UN experts warned early that Palestinians were at serious risk of genocide, and South Africa’s case at the International Court of Justice has already produced provisional orders instructing Israel to prevent genocidal acts and allow more humanitarian aid. Major rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, argue that Israel’s operation involves genocidal acts and the crime against humanity of extermination.

Any international stabilization force of the kind Barrack and Fidan are discussing would therefore have to operate under the shadow of ongoing genocide proceedings and war-crimes investigations.

Fidan said Turkey is ready to “do whatever it takes” to support peace efforts, including the potential deployment of Turkish troops as part of the Gaza mission. He described wide-ranging talks over the proposed ISF, from deployment and rules of engagement to which states might contribute personnel. “Thousands of details, questions are in place,” he was quoted as saying in regional media.

In his view, the first task of any such force should be to create a physical and security separation between Palestinians and Israelis along the border, and only then move on to other issues. The mission would need a trained Palestinian police contingent and local governing structures in Gaza capable of forming what Fidan called a “peace committee” to anchor the transition.