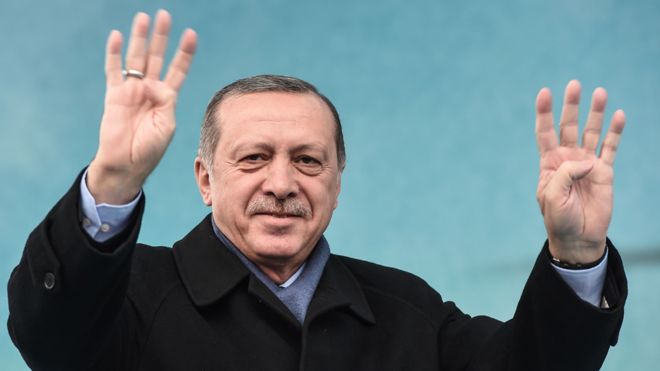

The four-finger salute – the “rabaa” – came from Muslim Brotherhood protests in Egypt in 2013

From humble beginnings Recep Tayyip Erdogan has grown into a political giant, reshaping Turkey more than any leader since Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the revered father of the modern republic.

But in the past year the economy has deteriorated, with inflation rising to some 20%, a weaker Turkish lira and unemployment reaching about 15%.

Mr Erdogan’s Islamist-rooted AK Party won the 31 March local elections nationally, but lost in the three biggest cities – Istanbul, the capital Ankara and Izmir.

Losing the Istanbul mayorship narrowly to the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) was a bitter blow to Mr Erdogan, who was the city’s mayor in the 1990s.

The AKP (Justice and Development Party) alleged voting irregularities in Istanbul, and the supreme election council finally decided to annul that result, ordering a re-run of the city’s election on 23 June.

The cancellation was highly unusual and condemned by the opposition, which accused the supposedly independent electoral judges of bowing to political pressure.

Istanbul is a key battleground for the AKP, even though most of the party’s voters are in small Anatolian towns and rural, conservative areas.

Beefed-up presidency

Mr Erdogan first rose to prominence in Istanbul, now a city of some 16 million. It was there and in Ankara that the AKP turned local success into a national political steamroller, becoming Turkey’s dominant party for years.

In June 2018, Mr Erdogan won a new five-year term after securing outright victory in the first round of a presidential poll.

It granted him sweeping new presidential powers, won in a controversial referendum in 2017. That constitutional change was tight, however – the Yes vote was 51%.

His powers include:

- Directly appointing top public officials, including ministers and vice-presidents

- The power to intervene in the country’s legal system

- The power to impose a state of emergency

Beefing up the presidency was accompanied by a massive purge of state institutions, following a July 2016 coup attempt which nearly toppled Mr Erdogan. His grip on power was seriously challenged by military officers – and his response was mass arrests and show trials.

The crackdown drew a chorus of criticism from Western politicians and human rights groups.

Image copyright AFP Image caption Ankara, 16 July 2016: Erdogan supporters thwarted a military coup in a night of drama

Image copyright AFP Image caption Ankara, 16 July 2016: Erdogan supporters thwarted a military coup in a night of drama

In 1960 and three more times in later decades the Turkish army intervened in politics, seeing itself as the guarantor of Kemal Ataturk’s secular republic.

Its shadowy nationalist influence behind the scenes came to be known as “the deep state”.

The AKP has shown a fierce determination to clip the military’s wings.

The failed 2016 coup claimed at least 240 lives and, according to his officials, also came close to killing Mr Erdogan, who had been staying at the Aegean holiday resort of Marmaris.

Yet he was back in less than 12 hours, having outmanoeuvred the plotters.

He appeared on national TV and rallied supporters in Istanbul, declaring he was the “chief commander”. But the strain on the president was clear when he sobbed openly while giving a speech at the funeral of a close friend, shot with his son by mutinous soldiers.

His critics call him an autocratic leader intolerant of dissent, who harshly silences anyone who opposes him.

And dissenters range from a 16-year-old arrested for insulting the president to a former Miss Turkey who got into trouble for sharing a poem critical of the Turkish president.

Image copyright AFP Image caption Erdogan supporters like his tough language and defence of traditional Muslim values

Image copyright AFP Image caption Erdogan supporters like his tough language and defence of traditional Muslim values

Purge of public servants

Mr Erdogan came to power nationally in 2002, a year after the formation of the AKP. He spent 11 years as Turkey’s prime minister before becoming the country’s first directly-elected president in August 2014 – a supposedly ceremonial role.

His silencing of critics has caused alarm abroad, contributing to frosty relations with the EU, which has stalled Turkey’s bid to join the bloc.

Since the thwarted coup, more than 50,000 people have been detained, including many soldiers, journalists, lawyers, police officers, academics and Kurdish politicians.

The authorities have sacked an estimated 150,000 public servants, and there are widespread complaints of AKP-inspired intimidation.

Image copyright AFP Image caption“Freedom for jailed journalists”: More than 100 journalists have been arrested since the abortive coup

Image copyright AFP Image caption“Freedom for jailed journalists”: More than 100 journalists have been arrested since the abortive coup

Mr Erdogan says the plot was engineered by Fethullah Gulen, a US-based Muslim cleric who used to be an ally.

Mr Gulen heads a global network of supporters – including Gulen schools – and his Hizmet movement has penetrated many areas of Turkish life. But he strongly denies plotting against the AKP government.

Mr Erdogan’s authoritarian approach is not confined to Turkey’s borders. His bodyguards harassed reporters in the US, and a German satirist was investigated in his home country for offending Mr Erdogan on TV.

Rise to power

Born in February 1954, Recep Tayyip Erdogan grew up the son of a coastguard, on Turkey’s Black Sea coast.

When he was 13, his father decided to move to Istanbul, hoping to give his five children a better upbringing.

As a teenager, the young Erdogan sold lemonade and sesame buns to earn extra cash.

He attended an Islamic school before obtaining a degree in management from Istanbul’s Marmara University – and playing professional football.

1970s-1980s – Active in Islamist circles, member of Necmettin Erbakan’s Welfare Party

1994-1998 – Mayor of Istanbul, until military officers made power grab and banned Welfare Party

1999 – Jailed for four months after he publicly read a nationalist poem including the lines: “The mosques are our barracks, the domes our helmets, the minarets our bayonets and the faithful our soldiers”

Aug 2001 – Founds Islamist-rooted AKP with ally Abdullah Gul

2002-2003 – AKP wins solid majority in parliamentary election, Erdogan appointed prime minister

June 2013 – Unleashes security forces on protesters trying to protect Gezi Park, a green area of Istanbul earmarked for a building project

Dec 2013 – Big corruption scandal batters his government – three cabinet ministers’ sons are arrested, Erdogan blames Gulenists

Aug 2014 – Becomes president after first-ever direct elections for head of state

July 2016 – Survives attempted coup by factions within the military

April 2017 – Wins referendum on increased presidential powers

Muslim revival

Mr Erdogan has denied wanting to impose Islamic values, saying he is committed to secularism. But he supports Turks’ right to express their religion more openly.

Some supporters nicknamed him “Sultan” – harking back to the Ottoman Empire.

Image copyright REUTERS Image caption Some secularist critics bristle at the sight of Mr Erdogan’s wife Emine (left) in a headscarf

Image copyright REUTERS Image caption Some secularist critics bristle at the sight of Mr Erdogan’s wife Emine (left) in a headscarf

In October 2013 Turkey lifted rules banning women from wearing headscarves in the country’s state institutions – with the exception of the judiciary, military and police – ending a decades-old restriction.

Critics also pointed to Mr Erdogan’s failed bid to criminalise adultery, and his attempts to introduce “alcohol-free zones”, as evidence of his alleged Islamist intentions.

A father of four, he has said “no Muslim family” should consider birth control or family planning. “We will multiply our descendants,” he said in May 2016.

He has extolled motherhood, condemned feminists, and said men and women cannot be treated equally.

Dominant landmark

Critics see a lavish new presidential palace as a symbol of Mr Erdogan’s grandiose ambitions.

Overlooking Ankara, the 1,000-room Ak Saray (White Palace) is bigger than the White House or Kremlin, and it cost even more than the original £385m ($482m) price tag.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES Image caption Much controversy has surrounded Mr Erdogan’s sprawling presidential palace in Ankara

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES Image caption Much controversy has surrounded Mr Erdogan’s sprawling presidential palace in Ankara

Mr Erdogan initially owed much of his popularity to economic stability, with an average annual growth rate of 4.5%. Turkey became a manufacturing and export powerhouse.

But in 2014 the economy began flagging – growth fell to 2.9% and unemployment rose above 10%.

He has backed some Syrian opposition groups in their fight against Bashar al-Assad’s government in Damascus.

He sometimes gives a four-finger salute – the “rabaa”- in solidarity with Egypt’s repressed Muslim Brotherhood.

His tentative peace overtures to the Kurds in south-eastern Turkey soured when he refused to help Syrian Kurds battling Islamic State jihadists.

Like previous Turkish leaders, he has cracked down hard on the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Source: BBC