Defense Secretary Mark Esper telephoned his Turkish counterpart on July 29 for the first time since formally taking the Pentagon’s helm, and the call did not go well. According to the Turkish read-out of the phone call, Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar demanded that the United States grant Turkey a buffer-zone in northern Syria extending 20 miles into the country.

Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar and acting US Secretary for Defense Mark Esper shake hands during a NATO Defence Ministers meeting in Brussels, Belgium

Virginia Mayo/Pool via REUTERS

Turkey justifies its demand in the accusation that it alone can provide security and that Kurdish-controlled regions in northern Syria are terrorist dens. Specifically, Turkish officials argue that the Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, controls the Kurdish cantons in northern and eastern Syria.

Akar has said that if the United States does not acquiesce to Turkish demands, that Turkey will launch a full-scale military operation into northern Syria.

Are fears of Kurdish terrorism and self-governance really motivating Turkey’s increasingly aggressive demands?

I have visited the Kurdish-controlled regions of northern Syria twice over the last five years: In January 2014, and again earlier this month. What the Kurds — and the Sunni Arabs, Christians, Yezidis, and others with whom they worked — have achieved is remarkable.

With very little money, they have provided security and a tolerant society. While Turkey provided support for Islamist extremist groups and opened its borders to thousands of Islamic State recruits, the People’s Protection Units, YPG, its female equivalent the Women’s Protection Units, YPJ, and the subsequent Syrian Defense Forces distinguished themselves for pushing back and ultimately defeating the terrorist groups.

Indeed, for all Turkey and its partisans complain about U.S. support for Kurdish groups in Syria, the United States sought to partner with Turkey initially, but concluded that defeating the Islamic State required working with its opponents rather than its enablers. While Akar says the entirety of the region is a PKK terror state, PKK founder Abdullah Öcalan’s portrait is far less present in the region now than it was five years ago. I am on the record criticizing PKK actions in the past and also questioning PKK political philosophy now, but the group has evolved. Importantly, a Belgian court recently ruled that the PKK was not a terror group.

Even if the PKK or, more likely, some of its offshoots, do conduct armed operations against Turks, two facts remain: First, Turkey conducts far more political assassinations of Kurdish leaders than Kurds do of Turks; and, second, that there is no evidence that Kurds have launched any terror attacks from Syria. Most recently, for example, assailants assassinated a Turkish intelligence officer in Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan. The Turks blame that operation on the PKK, but even Turkish reports suggest that it was Kurds from Turkey and perhaps Iraq who were responsible, and not Kurds in Syria.

If counter-terror concerns do not motivate Turkey’s demands, what do? Three factors:

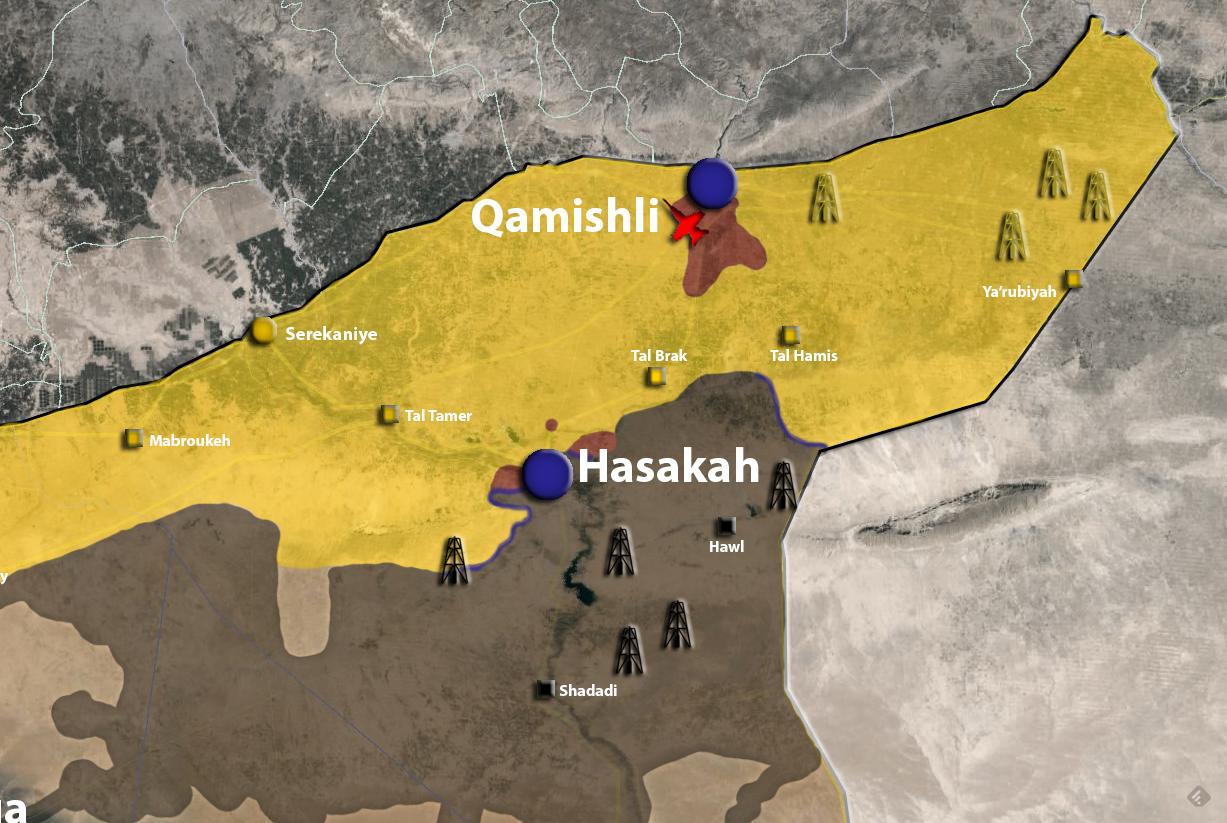

First, Turkey seeks a landgrab. In its previous operation in Afrin, Turkey engaged not in counter-terror, but in ethnic cleansing. A 20-mile buffer would give Turkey control not only of most Kurdish-governed towns and cities: Qamishli, Kobane, Amudeh, Malikiyah (Derik), Ain Issa, and Manbij. A Turkish buffer on the Syrian side of the border could spark civil war as Kurds who fled Turkey have nowhere else to go. If Turkey is truly concerned about terror, it could create a buffer within its own territory. But Turkish diplomats and generals must recognize that Turkish troops in Kurdish regions of Syria would be about as provocative as Armenian or Greek troops inside Turkey. In sum, further Turkish deployments into Syria are a non-starter and perhaps even reason for a far less limited war.

Second, Erdoğan wants a military campaign to distract Turks from his own failings. Turkey’s economy is teetering. Blaming enemies (or former allies as in the case of Fethullah Gülen) loses its credibility when it is done repeatedly. Erdoğan’s repeated losses in Istanbul elections further shakes the Turkish leader’s confidence. As modern Turkey nears its centenary, Erdoğan recognizes that the only thing Turkey’s founder Atatürk could claim that Erdoğan cannot is a great military victory. Ironically, Erdoğan’s hubris might embroil Turkey into a war and terror campaign that may ultimately end in its division.

Third, and perhaps most important, is Turkey’s thirst for oil. Lacking its own gas and oil resources, Turkey has long positioned itself as an energy hub. Pipeline transit fees bring Turkish coffers billions of dollars annually. Turkey’s aggression in Cyprus is motivated as much by a desire to maintain Turkey’s (and Russia’s) monopoly over pipelines as it is a desire to acquire oil and gas resources of its own. The vast majority of Syria’s oil resources would also fall in the “buffer zone” that Turkey seeks to occupy. In effect, what Turkey seeks is not only the expulsion of Syrian Kurds from the buffer zone, but possession of the oil reserves their historic towns and villages sit over. This would be a boon not only for Turkey’s economy but likely also for Erdoğan himself, as there are few major business deals today in Turkey from which Erdoğan or his family members do not profit.

Esper was correct to identify China as the greatest long-term strategic threat to the United States, but the job of the defense secretary is not only to address the long-term threats but also the short-term crises. If Esper wants to prevent a growing crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean or Syria, it is crucial he tell Akar there will be no buffer in Syria, and no more Turkish troops on Syrian soil. He should not fall victim to the Turkish game of staking out extreme, exaggerated positions in order to solicit supposed compromises that are equally untenable. The answer to Turkey must be no.

The best way to address a bully is to stand up to him, not to appease him.

By Michael Rubin

Source:AEI