Banks are being pushed to lend with the same reckless abandon.

İşbank, one of Turkey’s largest private banks, has warned that the non-performing loans (NPLs) in its portfolio could reach 7.5% of its total loan book by the end of this year, up from a previous estimate of 6%.

Deputy CEO Senar Akkuş, during a recent earnings call, blamed weak demand for new loans as one of the main reasons behind the increase in the bank’s NPLs, since weaker credit growth renders the portion of soured loans relatively larger when compared to total loans,

Bad loans in Turkey have almost doubled since last year’s currency and financial crisis lopped off roughly a third of the Turkish lira’s value, making repayment of loans denominated in dollars or other foreign currencies much more difficult. By the peak of the crisis, foreign currency loans accounted for a staggering 40% of the the country’s banking sector’s total assets.

Many of the delinquent loans have since been restructured. At the beginning of this year, after pressure from President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, state-owned banks gave struggling bank customers and small businesses an offer most of them could not refuse: to consolidate their debts at one of the state lenders, which then paid off the money they owed their respective banks. This effectively shifted consumer and small-business debts, particularly non-performing debts, from banks to state entities, which become a form of “bad bank.”

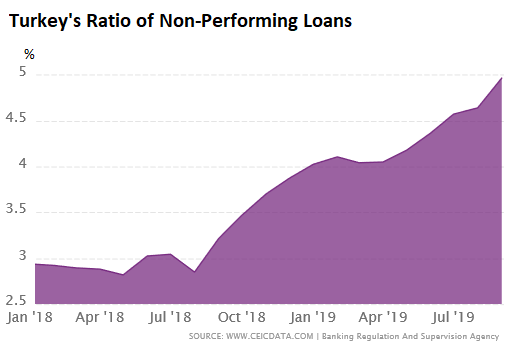

Despite all the assistance provided by Turkey’s state-owned bad banks, the NPL ratio of Turkey’s regular banks reached 5% in September for the first time since 2010. Through mid-2018, before the crisis was beginning to bite, the NPL ratio was mostly around 2.8%. It is expected to rise to 6.3% by the end of this year, according to Turkey’s banking watchdog, the BDDK (chart via CEIC):

In September, the BDDK forced banks to take losses on $8 billion of bad loans and set aside loss reserves — a move that some of the larger banks, saddled with some $20 billion in loans that construction and energy companies could no longer service, had heretofore resisted since it would mean acknowledging the bad debts as losses on their books.

The banks had hoped that Turkey’s Treasury Ministry would do more to shield them from the losses incurred by defaulting loans, as has already happened in other bad debt-infested jurisdictions, such as Italy where a state guarantee program for banks’ bad loans shields investors from the risk of losses incurred on the senior (or least risky) tranches of non-performing loan securitizations.

Without such assistance, banks in Turkey could face tough decisions in the months ahead over whether to sell or restructure the souring debt on their books, most of which are a hangover from the cheap loans, often denominated in foreign currencies, that the banks extended to the construction sector, which is dominated by government cronies. These cheap loans were a key plank in Turkey’s 15 year debt-fueled economic boom.

Now, Erdogan is determined to use the considerable sway he holds over Turkey’s economy to recreate that boom. To do that, he needs lower interest rates. Turkey’s recently appointed central bank chief, Murat Uysal, handpicked for the job by Erdogan himself, appears to be happy to oblige having already slashed rates from 19.75% to 14%. Of note, the annual inflation rate shot up during the currency crisis and ran above 20% through January this year, but has since been settling down.

Erdogan also needs the banks, both private and state-owned, to begin lending with the same reckless abandon as they did before the crisis, even as they grapple with rising levels of defaulting debt from the last boom.

To that end, in August the central bank, under Uysal’s direction, slashed the required reserve ratio for banks with loan growth rates from 10% to 20% and raised the return on those reserves, from 13% to 15%. Banks that don’t increase their annual loan growth above 10% are required to hold more reserves at the central bank and receive returns of just 5% on those reserves. State banks stand to benefit the most from the changes since they’ve been at the forefront of government efforts to boost lending.

There are tentative signs that the tactic is beginning to bear fruit. The total stock of mortgages extended by local lenders increased from 179 billion Turkish Lira ($30 billion) at the end of July to 189 billion lira ($33 billion) in the second week of October, as banks slashed borrowing costs for potential home buyers. The three biggest public banks, Ziraat, Vakifbank and Halkbank, are once again at the forefront, slashing monthly interest rates on their corporate loans and mortgages below Turkey’s benchmark interest rate (14% APR).

For now, it appears to be working. After suffering their deepest downturn in six years in the first half of the year, home sales staged a miraculous recovery in late summer, increasing by 5.1% year-on-year in August and 15.4% in September. Mortgaged sales surged threefold in August on an annual basis and five fold in September, although they were still 26% lower in the first three quarters of 2019 than they were during the same period of 2018.

But there could be a price to pay for all this largesse. In the case of Ziraat Bank, Turkey’s biggest state-run lender, which has been leading the charge to reanimate lending as well as restructure billions of lira of debt owed by business as consumers, its net income dropped by 32% in the first three quarters of 2019 compared to same period a year earlier. The bank is controlled by Turkey’s sovereign wealth fund, which in turn is chaired by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose grip over Turkey’s economy, through his unchallenged control of the Ministry of Finance, the state-owned banks, the Istanbul Stock Exchange and the central bank, has never been greater.

By Nick Corbishley, for WOLF STREET.