As recently as this weekend, Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan reiterated his unorthodox theory that lower interest rates will generate a “new economic model” for his country.

The president has said that cutting rates will bring down inflation and raise investment, employment and exports, enhancing Turkey’s independence from other countries.

Yet his economic experiment of lowering interest rates in the face of inflation, rather than raising them, has plunged his country into crisis with a collapsing currency, soaring prices, companies struggling with the costs of inputs and deep hardship, particularly among the poorest.

This indicates that Erdogan’s notions are deeply flawed — as does standard economic theory, which suggests higher interest rates are needed to defend a currency by deterring capital outflows, bearing down on domestic spending and demonstrating the authorities are serious in seeking to prevent an inflationary spiral.

Inflation in Turkey is heading towards 30 per cent after the lira lost more than half its value against the US dollar this autumn — despite a rebound late on Monday after Erdogan announced measures to compensate holders of lira in banks in the event of further currency depreciation.

Yet the economics community has itself questioned the role of hot money flows into and out of emerging economies and traditional theories, led by professor Hélène Rey of the London Business School, who noted in 2013 that emerging markets were often at the mercy of capital flows driven by the Federal Reserve’s policies and those of other major central banks.

The IMF has even sketched out a model in which higher interest rates could lead to higher inflation. The working paper by former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard and colleagues noted that large capital inflows into an emerging economy — often brought about by high interest rates — can lead to “credit booms and rising output” and inflation.

But although the IMF — the high priest of economic orthodoxy — publishes papers such as this, those circumstances do not apply to Turkey.

The country has run persistent deficits on its current account as imports regularly exceed exports, and suffers from stubbornly high inflation: the annual rate has been in excess of 10 per cent for almost all of the past five years. This suggests an underlying price growth problem that is embedded in the system and which policy has done little to eliminate.

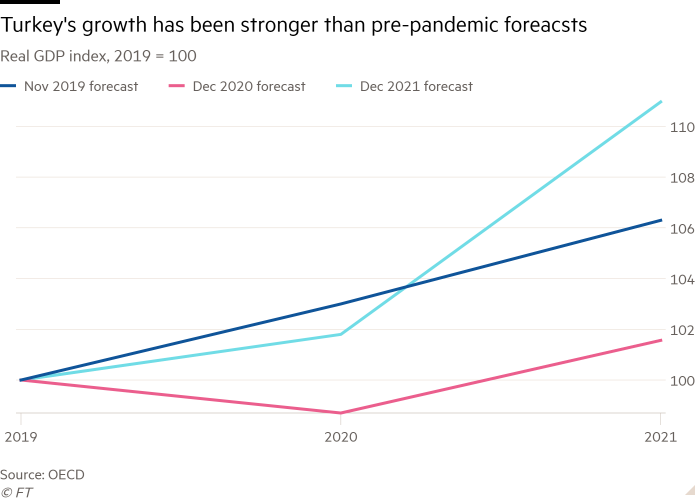

Earlier this month the OECD in Paris said that Turkey’s inflationary pressures had been further boosted this year by subsidised loans to domestic companies since the start of the pandemic, which helped fuel export-led “buoyant growth”, leaving its 2021 output higher than the OECD had expected before Covid-19 hit.

The OECD also warned that Turkey was likely to be “subject to potential further pressures from wages, import costs and producer prices”.

Professor Dani Rodrik of the Harvard Kennedy School said that for years Erdogan had ridden a wave of capital inflows that were attracted to Turkey by slightly higher interest rate margins.

“One of the myths of financial globalisation is that it enforces macro[economic] discipline,” Rodrik said, suggesting that financial markets would ensure countries ran credible and sustainable policies that attracted foreign cash. “In Turkey, it was the opposite. Turkey’s economic experiment ran much longer than it should have, thanks to the more elastic supply of finance. The economic costs will be larger as a result.”

Both Rodrik and the IMF argue that, even if higher interest rates helped attract inflows that raised spending and domestic inflation, the correct response by Ankara would have been to offset the effect with tighter policy, accepting slower growth in order to shore up longer-term stability and prevent precisely the crisis of confidence that Turkey has suffered in recent weeks.

Instead, Erdogan did the opposite, aided by a handpicked central bank governor. Turkey cut its short-term policy rate from 19 per cent in September to reach 14 per cent on December 16, in a series of expansionary moves.

The intention was to gradually lower the value of the Turkish lira and boost exports by increasing the competitiveness of smaller manufacturing companies, while also shifting spending from imports to domestic goods and services.

Although the current account deficit has moved into surplus since August, it has come at a huge cost to the credibility of Ankara’s economic policy and the livelihoods of Turkey’s population.

The official inflation rate topped 20 per cent in November with prices rising 3.5 per cent that month alone. Many observers consider this an underestimate of the true pace of inflation. Even so, it is expected to jump higher in December when the effects of the crash in the Turkish lira show up in import prices.

Worse, the lira’s plunge has boosted the debts of companies and the government, which have increased their foreign currency borrowings. Turkey’s non-financial corporate debt has risen by 20 percentage points of gross domestic product since the pandemic started, the highest among emerging economies, according to OECD estimates.

Even interest rate cuts no longer ease financial conditions for companies, because the financial markets now demand greater compensation for the risk. Turkish government bond yields have risen sharply as foreign and domestic investors lost confidence in the lira and sought the safety of hard currencies.

With import prices soaring, the economic circumstances threaten to crush domestic demand; a recent 50 per cent rise in the minimum wage will wipe out the cost advantages of the currency depreciation, according to Tim Ash of BlueBay Asset Management.

“If [Erdogan] had managed to hold [the line] when there were 10 lira to the [US] dollar, maybe they had a chance but, now inflation is out of the bag, the competitive advantage will go out of the window and we are in a devaluation inflation spiral,” Ash said.

Source: FT