Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has announced an ambitious plan to encourage the return of Syrian refugees, a hot-button issue increasingly dominating Turkey’s agenda ahead of elections next year. But his move is hardly more than a return to an already failed project.

Three years ago, Erdogan had presented a plan at the UN General Assembly to move 2 million Syrian refugees to prospective new settlements in northern Syria, but he failed to muster international support as the plan required the creation of a safe zone and multibillion-dollar funds.

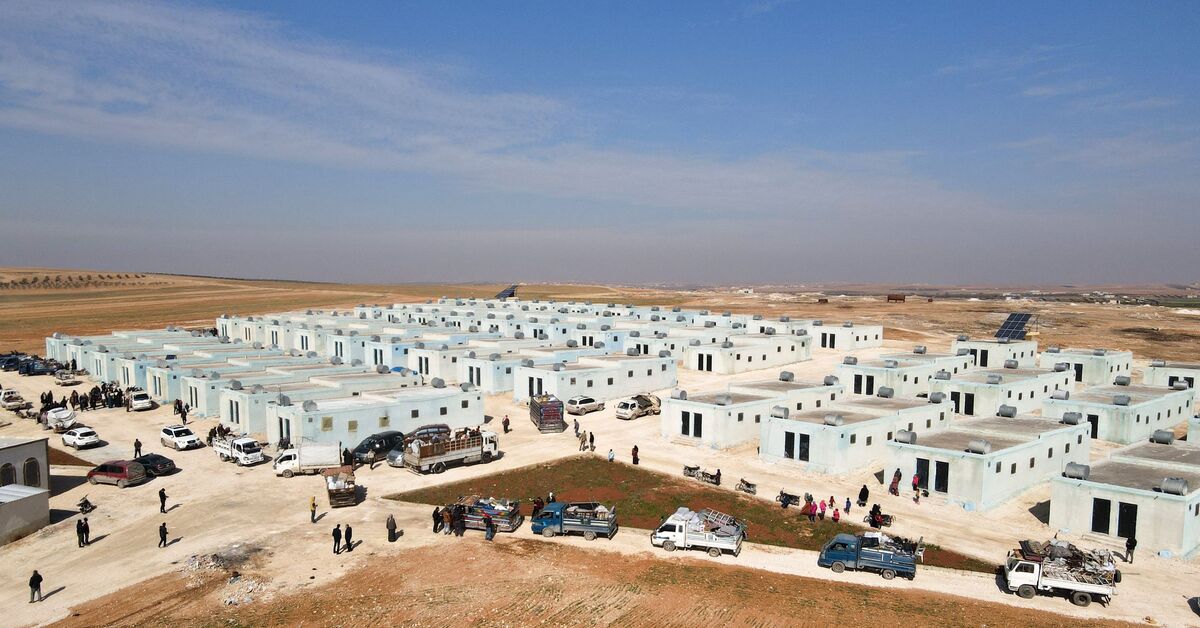

Earlier this week, Erdogan spoke by video link at the inauguration of cinder block homes in northern Syria intended for refugees in Turkey, noting that 500,000 Syrians had so far returned to safe regions in the country. “Now, we are preparing for a project that will secure the voluntary return of 1 million of our Syrian brothers,” Erdogan said. “The project, which we’ll carry out in cooperation with [opposition-affiliated] local councils in 13 areas, is rather comprehensive. It will cover all needs of daily life, from housing to schools and hospitals, as well as a self-sufficient economic infrastructure, from agriculture to industry.” As for the cinder block homes, he said over 57,000 homes out of 77,000 planned had been already built, and 50,000 families had settled in. Ankara aims to increase the total to 100,000 homes, he added.

As recently as March, Erdogan insisted his government would not send the refugees back, evoking an Islamic concept of solidarity. His U-turn follows opposition pledges to get the Syrians to go, which have grown more vocal as the elections approach, mirroring the growing discontent of a populace struggling with severe economic woes.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu, leader of the main opposition Republican People’s Party, pledges that, once in power, he would drastically change Ankara’s Syria policy and seek a deal with Damascus for the return of all Syrians in two years. His ally, Meral Aksener of the Good Party, also promises to reconcile with Damascus and send the refugees back. Similarly, the Democracy and Progress Party and the Felicity Party say Ankara should focus on peace-making in Syria so that the refugees can return. The Victory Party appears to have made the issue its sole election platform, with its leader sharing a meme that depicts a bus advertising “one-way runs [for refugees], coming up in 2023.”

According to government-controlled media, Erdogan’s plan is based on the following eight points:

- The returns will start from populous regions such as Istanbul, Ankara, Konya, Adana and Gaziantep.

- The Syrians will return to regions where stability and security have been ensured. Local councils in 13 areas, chief among them Azaz, Jarablus, al-Bab, Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ain, will be offered assistance for the project.

- More areas will be allocated for the construction of cinder block homes by charity groups in coordination with Turkey’s emergency management agency.

- Small industrial estates and commercial areas will be established to create employment.

- Infra- and superstructures will be built, including schools, hospitals and mosques.

- Vocational courses and workshops will be organized.

- Rehabilitative and educational activities will be a major focus.

- Funding will be sought from national and international entities.

According to Atay Uslu, chair of parliament’s migration commission, Ankara has launched a policy of “diluting” refugee populations, under which Syrians are no more admitted to 16 of Turkey’s 81 provinces and 800 neighborhoods in 52 other provinces and refugees offenders are being deported. “We are now setting international funds in motion for voluntary returns. New homes are being built. Once they are completed, the Syrians will be sent back. And if they don’t go, they will lose their temporary asylum status,” Uslu said last week.

As of mid-April, Turkey has deported more than 19,000 Syrians on law-and-order grounds since 2016.

Back in 2019, Erdogan had brought up a plan to build 10 towns and 140 villages in a border stretch inside Syria east of the Euphrates, extending to a depth of 32 kilometers (some 20 miles), to resettle 1 million refugees. In the second phase, another 1 million refugees would be resettled to an area stretching from the south of the M4 highway to Deir ez-Zor. The plan aimed to expand Turkish military control along the border in a bid to ease Turkey’s refugee burden but also to alter local demographics to the detriment of the Kurds.

Ankara has come to acknowledge that a realistic approach to the refugee issue requires an end to confrontational policies and making peace with Damascus. Yet contacts with the Syrian government have failed to go beyond the level of intelligence officers. Ankara is reportedly hoping for a new chapter based on partnership to undo the Kurdish-led self-rule in northern Syria, while Damascus demands that Turkey end its military presence and support for armed rebels in Syria. In other words, Erdogan is not ready to profoundly change his policy, and Damascus is unwilling to take a course that could reward Erdogan politically ahead of elections.

And even if favorable conditions are provided for their return, most of the Syrians in Turkey are unwilling to go back. According to a survey sponsored by the UN refugee agency, the rate of Syrians who say they don’t plan to return increased to 77.8% in 2020 from 16.7% in 2017.

In sum, Erdogan’s goal appears unrealistic in the current conditions. Hitherto efforts to encourage returns have yielded limited results amid continuing clashes in Syria, uncertainty over the future of Turkish-controlled areas and Idlib’s ongoing domination by factions designated as terrorist groups. According to the Interior Ministry, 492,983 Syrians have returned home as of April 4. The figure might be speculative, however, as the population of the areas to which the refugees are said to have returned is normally below half a million.

Moreover, data by Turkey’s migration agency show that the number of Syrians in Turkey has increased over the years despite the reported returns, standing at 3.7 million in late April. The figure stood at 2.2 million in 2015, when Ankara ended its open-door policy, rising to 2.8 million in 2016, when Turkey launched Operation Euphrates Shield, the first of its several military campaigns in Syria. About 52,000 Syrians have been resettled to third countries since 2014. Compared by years, the number of Syrians in Turkey dropped only once by about 47,000 in 2019 when Erdogan threatened to unleash the refugees on Europe. It rose by 65,000 in 2020, 96,000 in 2021 and some 25,000 in the first four months of 2022. Contributing to the increase are the newborns, along with those crossing the border illegally. Some 754,000 Syrian babies have been born in Turkey, the health minister said in March.

The number of Syrians who have made it illegally to third countries but remain registered in Turkey is unknown. Some observers suspect that Syrians who have moved on to Europe are being shown as having returned to Syria. Also, the homes of many Kurds displaced from Afrin have been taken over by militia allied with Turkey, and this, too, is often portrayed as successful resettlement. Such demographic interventions have taken place also in Ras al-Ain and Tell Abyad, though on a smaller scale.

Erdogan has been acting as if Azaz, Jarablus, al-Bab, Afrin, Tell Abyad, Ras al-Ain and Idlib will never return to the control of the Syrian state. Yet the refugee issue has increasingly hijacked Turkey’s political agenda amid growing economic and social grievances, driving him into a corner.

According to the same survey, 90% of Turks believe the Syrians are here to stay. Nevertheless, 85% of respondents want the refugees to be sent back or confined to camps. While 98% of the Syrians are now living in urban centers across Turkey, only 6.8% of Turkish respondents support co-habitation and 85.6% are opposed to Syrians acquiring citizenship and suffrage rights. As of March 31, about 201,000 Syrians have become Turkish citizens and nearly 114,000 of them are eligible to vote, according to Interior Minister Suleyman Soylu.

Source:Al-Monitor

***Show us some LOVE by sharing it!***